Unless He Be A Blockhead

By JIM KYLE

Few fellow Oklahomans are aware of it, but a massive fiction factory exists right in the middle of our state — and for more than 70 years has been turning out top-notch authors who have produced hundreds of best-selling books and movies. It’s still doing so.

You’ll undoubtedly recognize some of the titles. Among the best-known movies are “The Hallelujah Trail,” “Onionhead,” “Hondo,” and “Bend of the River.”

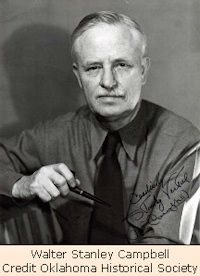

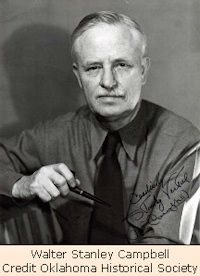

It began in 1938, when our very first Rhodes Scholar (who didn’t get his first bachelor’s degree during his lifetime) convinced The Powers That Be of the University of Oklahoma to let him establish courses in “professional writing.” Walter Stanley Campbell had already become a professional writer himself; his books about native American life had made that clear. Published under the pen name Stanley Vestal, they recounted events from the Indian viewpoint.

Many colleges and universities offered “creative writing” courses, but none of them provided much (or for that matter, any) guidance for anyone wanting to earn a living as an author. They concentrated on creativity, artistic value, and similarly literary subjects; Professor Campbell was teaching such a course himself, not at all happily. Many colleges and universities offered “creative writing” courses, but none of them provided much (or for that matter, any) guidance for anyone wanting to earn a living as an author. They concentrated on creativity, artistic value, and similarly literary subjects; Professor Campbell was teaching such a course himself, not at all happily.

University officials agreed to offer a course to train writers in professional techniques, but initially wanted to establish a school magazine in which to publish their work. That wasn’t what Professor Campbell had in mind. Not at all.

His plan to teach a would-be writer how to approach the task in a professional manner required that his students test their wings in direct competition with established writers. This meant providing instruction in such mundane material as “how to submit a story to an editor” and more importantly the technique of analyzing potential markets for one’s product.

One of the first things taught, in the first course, was a quotation from Samuel Johnson: “No man, unless he be a blockhead, writes, except for money.” That’s not always true. Sometimes we write just because we have something to say, with no regard for getting paid. Like here, for example. That’s okay — but it’s NOT professional. So I’m a blockhead. So what?

In the early days, the most accessible market for fiction was the pulp magazine. They barely exist today, but before and during WW2 they filled newsstands and provided the entertainment that we now seek from TV. Each specialized in some specific genre. There were westerns, detective stories, tales of flying derring-do, science fiction, horror — you name a subject, there was probably at least one pulp devoted to it.

With so many of them being printed every month, the need for material was huge. They didn’t pay much; the standard rate varied from half a cent to one cent per word, which meant that a writer would get only $25 to $50 for a 5,000-word story (the standard length). However in the late Thirties, that was very good pay. If a writer could sell one story every week, his family could be well fed.

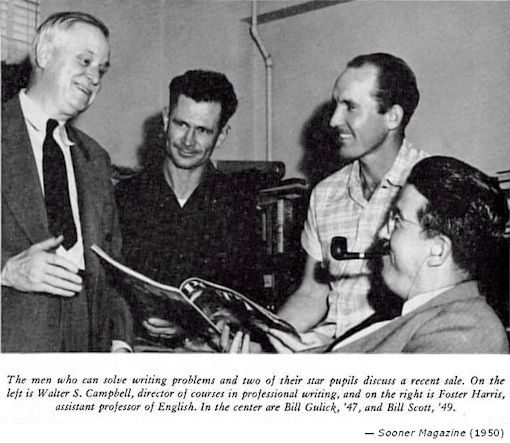

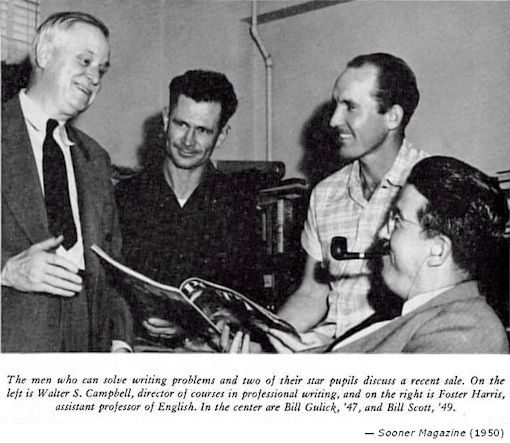

Campbell’s writings had been more scholarly than popular, so right at the beginning he brought William Foster Harris, one of the most prolific writers of westerns at the time with more than 800 short stories published by the pulps, into the program. Harris, who wrote as “Foster-Harris” and was known to his students simply as “Foster,” was expert in the mechanics of plotting, and also a more than capable editor. The entire program became known as the Campbell-Harris Professional Writing Program. Campbell’s writings had been more scholarly than popular, so right at the beginning he brought William Foster Harris, one of the most prolific writers of westerns at the time with more than 800 short stories published by the pulps, into the program. Harris, who wrote as “Foster-Harris” and was known to his students simply as “Foster,” was expert in the mechanics of plotting, and also a more than capable editor. The entire program became known as the Campbell-Harris Professional Writing Program.

Once a student had completed the initial courses under Campbell, Harris took over to hone the skills of would-be fictioneers. His classes were one-on-one, in his office. He required the student to write one new 5,000-word short story each week, and Foster would then critique it. After the first week, the student would have several stories in the rewrite process together with each new one. When Foster deemed one to be ready, the student would submit it to the market of his choice — and if it sold, that brought a better mark from Foster.

Actually, grades didn’t matter much, because until the early 1950s, the courses did not lead to any sort of degree. They were not part of the official curriculum of the English Department, and had no direct connection to the School of Journalism either. This was by design on the part of Campbell; his position was that no editor cared about a diploma when evaluating a submission. It was either acceptable, and bought, or it was not, and was rejected. The intent of the program was to train professional writers, not scholars.

Another difference became clear very early in the course. While “creative writers” worried endlessly about their writing styles, Campbell’s admonition was blunt: “Don’t worry about style. You can’t change it any more than you can change the shape of your face. Just write.” He also made it clear from the start that the program would not guarantee immediate success. The most he was willing to promise was that by providing the fundamental techniques and mindset, it would cut ten years off the time required to get there. In actual fact, many of his students reached the top levels more rapidly after completing the courses. Several did even before completing the program.

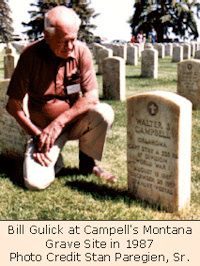

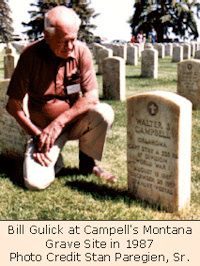

The list of top-flight authors trained by Campbell and Harris — either in the residence courses, by correspondence, or in the annual on-campus short course (unfortunately discontinued several years ago) — is far too long to include here. It includes among others Louis L’Amour (one of the first), Mary Higgins Clark, Fred Grove, Tony Hillerman, Bill Gulick, William R. Scott, Ed Montgomery, Neal Barrett, and Bill Burchardt (editor of Oklahoma Today magazine for 19 years before his retirement in 1979). More contemporary standouts include Norman’s Judith Henry Wall, Eve Sandstrom (“JoAnna Carol”) from Lawton, and Jean Hagar.

At least five winners of the Owen Wister Award presented annually for “Outstanding Contributions to the American West,” including Harris himself in 1974, are associated with the program. Other winners of the award include John Wayne, John Ford, and Clint Eastwood.

Relations between the Professional Writing Program and the rest of the English department were always somewhat strained because of the “no diploma required” philosophy, and when Harris was promoted in the early Fifties the tension became great. Dr. Fayette Copeland, dean of the Journalism school at the time, suggested transferring the program into the J-School, and that happened on June 1, 1951 — just in time for me to claim some of my hours there for my minor in English, and others toward my major in Journalism.

Campbell died on Christmas day 1957 at the age of 80. Harris assumed leadership of the program, and brought in noted science-fiction author Dwight V. Swain as his assistant. Earlier, he had recruited Swain as his substitute when a serious illness in late 1951 felled him for most of a semester. In addition to writing short stories and novels, Swain was an accomplished screen writer, and in 1961 added courses in the writing of screenplays to the program.

Swain added considerably more than new courses to the professional writing program. His screenwriting background led to an emphasis on scene and structure that had been much less emphasized in the earlier approaches. His textbooks on this subject are still in demand.

In 1974, Harris retired. Jack Bickham, who wrote more than 70 novels and had joined the professional writing faculty in 1969, became the new director. Four years later, in May 1978, Harris died at the age of 74. Before Harris’ retirement, former students had endowed a $10,000 scholarship fund for outstanding students in the program; it’s still helping new writers today.

Swain retired early because of failing health. His replacement as Bickham’s assistant was Carolyn Hart, author of many mystery novels and still going strong although she left the program in the mid-Eighties to write full-time. Bickham retired in 1991. Deborah Chester and J. Madison Davis were then hired as permanent faculty to continue the program, and together with Scott Hodgson, Win Blevins, and Chris Borthick constitute the present faculty.

In the years since its founders retired, the program has grown immensely — but still retains the same basic philosophy of teaching a professional approach to the writers’ trade. So who were these people who created such a powerful fiction factory (or, if you prefer, boot camp for writers)?

Campbell was born Walter Stanley Vestal near Severy, KS, on August 15, 1877. His father died not long afterward, and his mother married James Robert Campbell, who later became the first president of what is now Southwestern Oklahoma State University in Weatherford. He adopted young Walter, who took his stepfather’s surname. When he began writing for publication, he created his pen name “Stanley Vestal” from his middle name and his birth surname.

Young Walter grew up in Weatherford, and was a member of the first graduating class from SWOSU (then known as Southwestern Normal School). However political issues had resulted in the school’s degree-granting authority being suspended for a short time in 1908, so he never got a diploma. He did, however, become the state’s first Rhodes Scholar, and received both a B.A. and an M.A. from Oxford University. The lack of his original diploma was corrected in July 2011, when SWOSU awarded his degree posthumously.

Upon returning to the U.S. in 1911, Campbell taught for a year in Kentucky, but gave it up to write full time. Having grown up in Cheyenne-Arapaho country and being quite familiar with native American people, he wanted to tell their stories. His biography of Sitting Bull is still the gold standard.

He joined the OU faculty in 1915, teaching English. When the U.S. entered WW1 in 1917, he took leave of absence from OU and joined the army, rising to captain in an artillery regiment. Upon leaving the army he returned to OU and remained there until his death. In the mid-20s he returned to writing professionally, and published several books — one of them a text titled simply “Professional Writing.” That one led to the program’s creation. He joined the OU faculty in 1915, teaching English. When the U.S. entered WW1 in 1917, he took leave of absence from OU and joined the army, rising to captain in an artillery regiment. Upon leaving the army he returned to OU and remained there until his death. In the mid-20s he returned to writing professionally, and published several books — one of them a text titled simply “Professional Writing.” That one led to the program’s creation.

During his lifetime, he wrote more than 20 books and over 100 shorter articles on the old West. He is buried at the Custer National Cemetery in Big Horn County, MT.

William Foster Harris was born August 7, 1903, near Sulphur in what was then the Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory. His mother was a teacher and his father was a wildcatter in the oil patch. He graduated from OU in the mid-Twenties as a geologist, and like his father went into the oil fields. His writing ability soon took him to the editorship of an oil-related newspaper. From there, his interest in the old West led him to begin writing for the pulp Westerns.

By the time Campbell tapped him to join the program in 1938, Foster had published more than 800 magazine pieces. Obviously, he knew what he was talking about. He spoke from successful experience. He reduced the essentials of plot mechanics to a simple formula based on two equations: 1+1=2 and 1-1=0. As he explained it in his “Basic Formulas of Fiction,” the first is the happy-ending plot, while the second is the opposite. The “1”s represent emotional forces, that are in conflict. The plus sign means “make the right choice” while minus means “wrong choice.” In a successful story, both plots exist: the hero gets 2 while the villain gets 0. By the time Campbell tapped him to join the program in 1938, Foster had published more than 800 magazine pieces. Obviously, he knew what he was talking about. He spoke from successful experience. He reduced the essentials of plot mechanics to a simple formula based on two equations: 1+1=2 and 1-1=0. As he explained it in his “Basic Formulas of Fiction,” the first is the happy-ending plot, while the second is the opposite. The “1”s represent emotional forces, that are in conflict. The plus sign means “make the right choice” while minus means “wrong choice.” In a successful story, both plots exist: the hero gets 2 while the villain gets 0.

His prototypical example is illustrated in part by the movie “High Noon” in which the hero (Gary Cooper) had promised his wife (Grace Kelly) that he would not kill anyone, only to be faced with the prospect of a returning badman who had sworn to kill him. The conflicting forces on the hero are “keeping his word” versus “self-preservation.”

The movie didn’t follow Foster’s example, though. As Foster explained it, his badman was basically a coward. His hero resolved the conflict by choosing to walk into the battle but never draw his gun, accepting death before dishonor. The badman, faced with a resolute lawman advancing fearlessly toward him, panicked and ran — thus destroying his reputation forever.

Foster also relentlessly pounded into us his notion of the “magic trinity” composed of the author, the reader, and the viewpoint character through whose eyes the story is told. Only when the author feels the conflicting emotions, and makes them clear in the viewpoint character, does the reader experience them and enjoy the story. Achieving this merger of three individuals into a single entity was the secret to becoming a successful storyteller — an art which I never mastered.

In the Winter 1964-65 issue of Oklahoma Today magazine, Goldie Capers Smith wrote of Foster’s philosophy about writing:

The writer with the Western viewpoint,” says Foster-Harris, “can write till he is ninety-seven and has to have help to totter to his typewriter each day. But his writing still sells.

Of the Western Story in the sense of a story set in the Old West, he says, “The spell of the Western is the spell of green pastures over the hill. Look at the popularity of Western movies and on TV. The hero always leaps on three or four horses and rides a few thousand miles to kill a few million bad men.” The girl in the Westerns is unimportant. “She’s just a trophy. Keep her on the shelf and award her to the hero. Let him decide what to do with her.”

Plotting, which many beginners find the bugaboo of writing, Professor Harris considers no problem at all. “The way to catch a plot,” he explains, “is the way to catch a woman. Pretend not to be interested.” The student who complains that it is impossible to find a new plot because all the plots have been used, he tells, “You don’t need a new plot. Just put a little parsley on the same old dish!”

I was in the program during what were possibly some of its best years: 1949-52. Just a year ahead of me, Tony Hillerman had graduated. By the time he died in 2008, he had published 29 books, including 17 mysteries featuring Navajo police officers Jim Chee and Joe Leaphorn. He had received every major honor for mystery fiction.

William R. Scott, who published “Onionhead” (made into a great movie starring Andy Griffith) under the pen name Weldon Hill to disguise its autobiographical roots, finished the courses the year that I began (he also wrote for The Covered Wagon, the campus humor magazine, as “Steinway Hemingbeck”). Neal Barrett, recently honored by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, was a classmate both at Classen in OKC and in the program at OU, although we were never close.

I don’t remember just how I learned of the program’s existence. Quite possibly, it came to my attention through the magazine Writer’s Digest, which I read religiously at that time and which was quite enthusiastic about the courses.

I do remember, though, that it wasn’t simple to get into in the first place. You couldn’t just sign up for it and start going to class. You had to fill out a detailed questionnaire, complete a sample story, and survive a one-on-one interview with Campbell himself if the written material passed muster.

One of the questions was “Why do you want to be a writer?” My somewhat flippant reply was “Because it beats working.” When Campbell got to that one during my interview, he chuckled. “I think you’ll discover otherwise,” he said. He was right. Nevertheless, he accepted my application, and I showed up for class with my box of Crayolas and pulp magazine in hand, as required.

The crayons and magazine were part of the technique to discover the scaffolding on which a pulp story was built. He assigned one color to “narrative verbs,” another to “description,” still another for “emotion,” and so forth. We were to go through a specified story in the magazine, marking each word with its appropriate color, then determine the amount of each color in the story by measuring the total length of its lines.

After doing this for each of the stories, we began to get a feel not only for the amount of each kind of content, but for the patterns in which they occurred. Our introduction to professional techniques had begun.

On the wall of Campbell’s oversized office which also served as the classroom was a small framed cartoon. It had four panels, each showing a person shouting a single word. The words were “Hey,” “You!” “See?” and “So.” One day after class, I asked Campbell about its significance.

“That’s the formula for non-fiction,” was his reply. “You begin with ‘Hey’ to grab the reader’s attention, follow immediately with ‘You’ to make it personal. When you do that, you have him hooked. The ‘See’ provides the main body of the article, and ‘So’ wraps it up neatly.”

That simple four-word formula is the most important single thing I learned in the entire three years I spent in the program. I’ve never been able to keep a fictional character alive long enough to tell a salable story, but “Hey, you! See? So” has bought me two homes over the years and kept food in the pantry since I learned it. Even before completing the courses, I had sold two non-fiction articles to national magazines, including a personality sketch of Bud Wilkinson to Sport Magazine.

If you look closely, you can see that I’m still using it right here. It works.

During my years in the newspaper business, I didn’t pursue magazine work seriously at first. However, after acquiring a family, I began writing for ham radio magazines to supplement a reporter’s pay. During my years in the newspaper business, I didn’t pursue magazine work seriously at first. However, after acquiring a family, I began writing for ham radio magazines to supplement a reporter’s pay.

After I left the Oklahoman and moved to the Los Angeles suburbs to become an electronics tech writer in the defense industry, the increased cost of living there made extra income a necessity — especially after the 100-hour weeks and their accompanying overtime pay came to an abrupt end. That’s when the formula really began to pay off — and bought my first house.

I became a contributing editor for a start-up magazine called 73 that was run by an editor with whom I had previously worked. He needed copy to fill its pages, promised to pay on acceptance, and I needed money. It was the start of a beautiful friendship. My typewriter filled half of those pages during the first year of publication, and I remained on the masthead as a contributing editor for 10 years. Some of my first published books were collections of articles written for 73.

I also wrote for more general electronics magazines, and even sold material to Mechanix Illustrated for its electronics section. This prolific output caught the attention of another magazine publisher who was planning to move his operation from California to Oklahoma City, and who offered to pay my moving expenses if I would work for him as an editor on three trade journals. Since my whole family was homesick, I jumped at the chance. I also wrote for more general electronics magazines, and even sold material to Mechanix Illustrated for its electronics section. This prolific output caught the attention of another magazine publisher who was planning to move his operation from California to Oklahoma City, and who offered to pay my moving expenses if I would work for him as an editor on three trade journals. Since my whole family was homesick, I jumped at the chance.

The editorship lasted just one year, but taught me about “the other side” of the publishing business. After it folded, I free-lanced for a couple of years before joining General Electric to write the service manuals for the very first “TV Typewriter” computer display terminal — and even then continued to write for publication on the side. During the free-lance years I published my first book; the count eventually passed 20, all on highly technical subjects.

Aside from the books, I did very little outside writing from 1965 until the mid-Eighties. I had discovered the joy of writing software; at G-E I had access to computers. This led me in a roundabout way to become active on the CompuServe network, a predecessor of the Internet, and that in turn resulted in my becoming a “sysop” or “system operator” for the on-line forum sponsored by Computer Language Magazine.

Discussions there brought me back into the magazine writing world, and I began selling a few articles to CLM. Those led to an offer by Allen Wyatt, at the time an editor with Que Publishing Company, for me to update, as a second edition, a book he had written. I jumped at the offer, and added a couple of chapters to the original, including one about the “undocumented” computer code that lay at the foundation of Microsoft’s Disk Operating System known as MS-DOS.

Prior to the 1989 release of “DOS Programmer’s Reference, Second Edition,” that code had been a closely guarded trade secret, known to only a handful of folk outside the Microsoft labs. What I had published was nowhere near all of it, of course, but it gained notice throughout what was then still a cottage industry providing PC software.

In 1990, a literary agent approached me to see if I was interested in joining a team that would produce an entire book devoted exclusively to the undocumented aspects. At almost the same time, my long-time employment with G-E, Honeywell, MPI, and BancTec Systems came to an end. Again, I jumped at it. “Undocumented DOS” turned out to be the closest thing to a best-seller I ever did, rising for a while into the top 20 for technical trade books, going into a second edition, and being translated into Russian and Japanese. Nobody ever made an offer for the movie rights to it, though — and it was a collaborative effort with four other fellows, anyway.

So looking back on more than 60 years as a published writer, I find it difficult to pinpoint all of the major landmarks I’ve passed — but I’m certain that my time with Campbell and Harris was the most significant of all of them. Even though I never completed a successful short story or sold a novel, they taught me what professional writing is all about. And their legacy lives on, not only in the accomplishments of those who learned directly from them, but in the program itself which continues to this day. |

Editor’s Introduction. In the last installment of Jim Kyle’s Memoirs, “We Didn’t Use Billy Clubs”, he left us with images and stories a war which wasn’t — the Korean Conflict, Police Action, or whatever other euphemism it was called by some. Shown here as a First Lieutenant in November 1953, I’m thinking that Jim just might be smiling because it was nearing his time to come home.

Editor’s Introduction. In the last installment of Jim Kyle’s Memoirs, “We Didn’t Use Billy Clubs”, he left us with images and stories a war which wasn’t — the Korean Conflict, Police Action, or whatever other euphemism it was called by some. Shown here as a First Lieutenant in November 1953, I’m thinking that Jim just might be smiling because it was nearing his time to come home. In this article, Jim takes as his title part of a famous quotation by the stuffy-looking Englishman Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) shown at left — I’ll leave it to Jim to say why, below. Although Jim Kyle may or may not take issue Johnson’s definition of a “blockhead” and whether he is one, you will certainly conclude just as I have that it just ain’t so. Samuel Johnson, as skilled and wise a writer and critic as he may have been, knew nothing of the Internet.

In this article, Jim takes as his title part of a famous quotation by the stuffy-looking Englishman Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) shown at left — I’ll leave it to Jim to say why, below. Although Jim Kyle may or may not take issue Johnson’s definition of a “blockhead” and whether he is one, you will certainly conclude just as I have that it just ain’t so. Samuel Johnson, as skilled and wise a writer and critic as he may have been, knew nothing of the Internet.