In the Oklahoma City history vernacular, the “Civic Center” phrase means the public buildings owned by Oklahoma City and/or County and their attending accouterments built between 1935 and 1937 in the area flanked by Harvey and Shartel (on the east and west) and by Couch Drive and Park Avenue & Colcord Drive (on the north and south), the main structures being the existing Oklahoma County Courthouse, City Hall, the Oklahoma City Music Hall, and the city law enforcement and jail facility on the east side of Shartel. Technically, it may also be said to include the parks along Couch Drive from Harvey to Broadway since they, too, lie within the tract vacated by the Rock Island Railroad in 1930. This article explores how the Civic Center came to be.

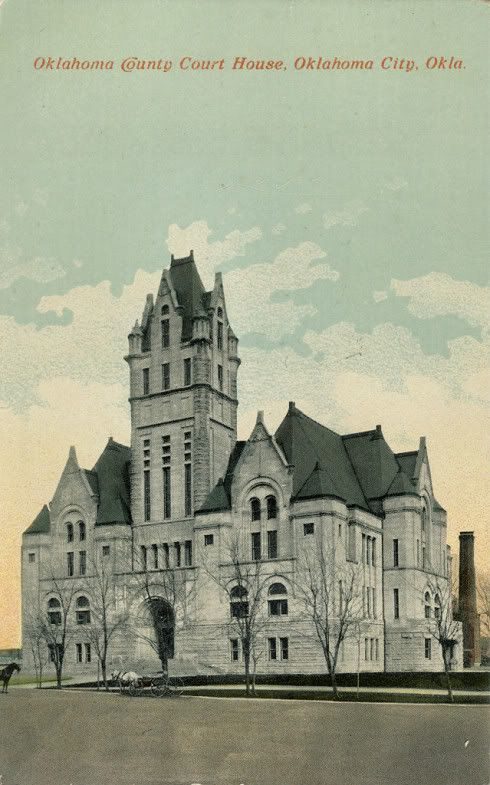

Inspirational credit for this article goes to the outstanding blogger Blair Humphreys and his great imagiNATIVEAmerica blog which focuses on Oklahoma City and, particularly, city planning. There, he lamented the passing of the beautiful old Oklahoma County Courthouse, shown below:

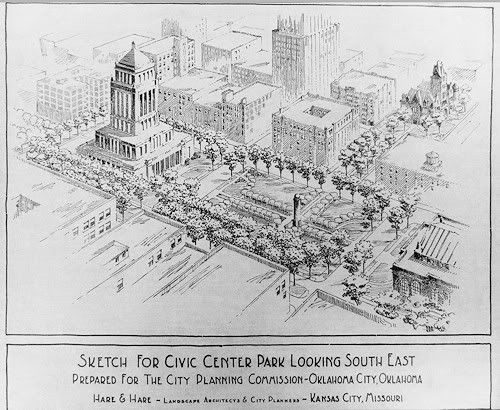

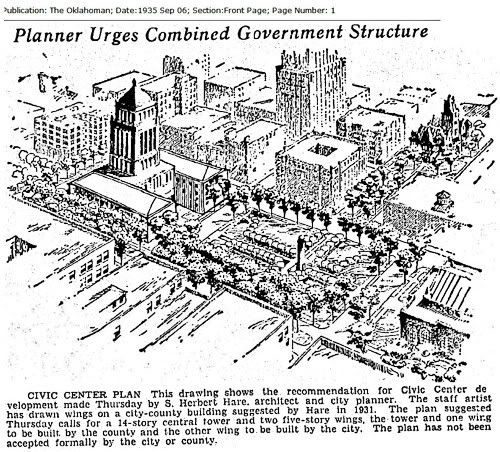

More particularly, he wondered why it came to be left out of the inclusive planning for the publicly owned buildings being contemplated in 1931. Click here to jump to the end of this article and see what happened to the old courthouse. What really torqued my interest, though, was this wonderful image which he’d located in his own research — in the image, note the presence of the old Oklahoma County Courthouse in the top right area of the drawing:

Whoa! What a fascinating historic drawing! Just seeing it was more than enough to get me hooked and I wanted to know more. Hence, this article came to be.

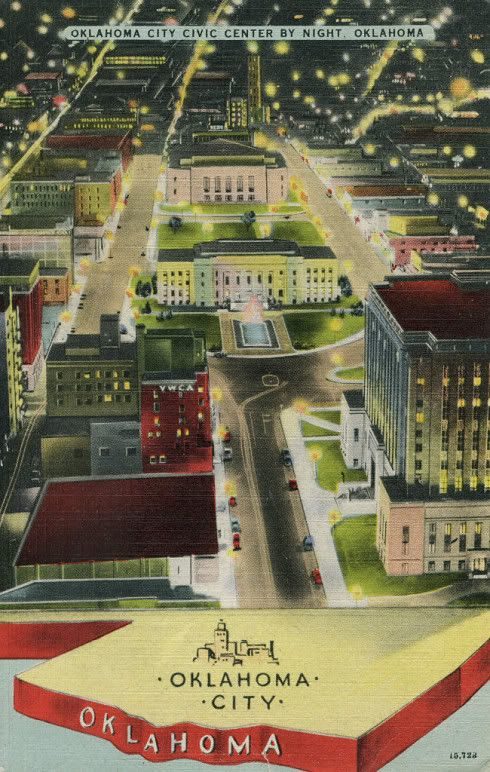

Civic Center Development. As already said, the “Civic Center” means four main buildings, three receiving the focus in the following vintage (late 1930s) postcard below, the Oklahoma County Courthouse (lower right), City Hall (center) and the Oklahoma City Music Hall (center top) (the city’s law enforcement and jail building is behind the auditorium but is not particularly distinguishable in the postcard):

It is recalled that, until the 1950s, “Park Avenue” was NW 1st Street and that, until the east/west railroad tracks were ripped from downtown, neither Couch nor Colcord Drives existed. Stepping back into the 1920s, the area encompassed by the Civic Center looked more like this:

The Petroleum Building, center background, was built in 1927

Credit Oklahoma City: Statehood to 1930 by Terry L. Griffith (Arcadia Publishing 2000)

The old Oklahoma County Courthouse is at the right edge

As the east/west railroad tracks came to be being going, going, but not yet gone, the area looked more like this:

For more about the history of the track removal, see this article. More easily seen in the larger image, Montgomery Wards is the “whitish” building at the right and the old Oklahoma County Courthouse is at the right edge of the photograph, probably taken in 1928 or 1929 (the Petroleum Building, built in 1927, is present, but construction of the Ramsey Tower and First National Bank has not yet started).

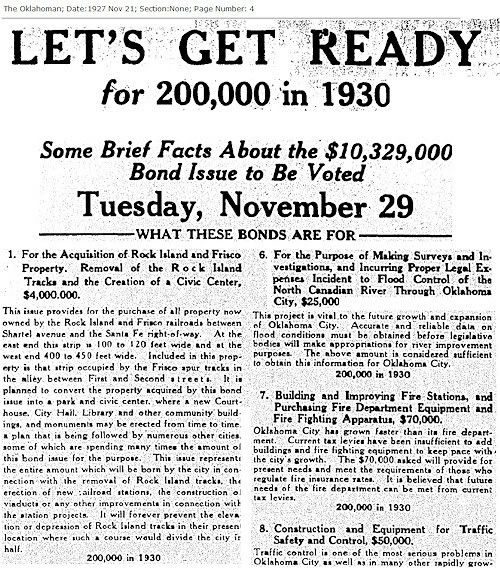

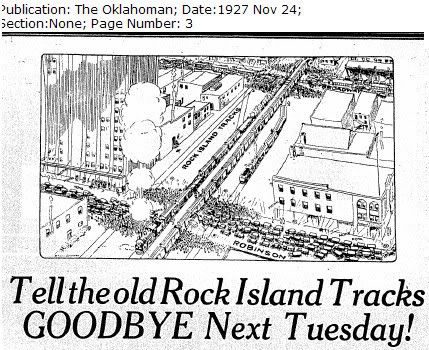

In late 1927, a bond election was presented to city voters, illustrated by the following pro-bond issue ads:

Larger image not available

Voters approved and by 1930-31 all downtown east/west tracks were gone. The Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad company got a bucket full of money in exchange for its quit claim deed to the property — more about this toward the end of this article.

Now, development of the Civic Center could proceed with dispatch. With dispatch, right? Well, not exactly.

The Great Depression came along at about the same time and economic issues doubtless caused some delays. As it developed, a substantial part of the Civic Center was funded by the federal government via its recovery programs (does that sound familiar these days?). Local controversies, though, also contributed to slowness in moving forward with dispatch. Exactly what buildings should be constructed, and where?

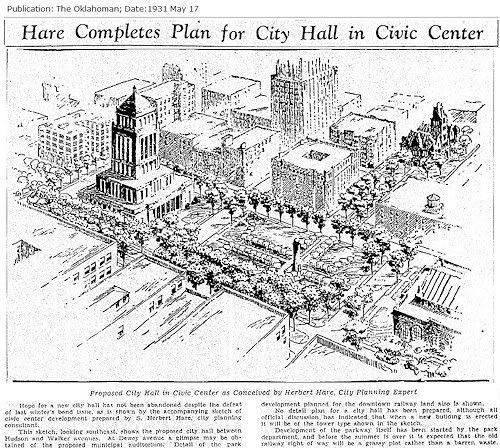

At some point, at least by 1931 but probably sooner, Oklahoma City engaged the services of Hare & Hare, a landscape architect and city planning firm operating out of Kansas City. As originally contemplated (I’ll call it the “Hare Plan”), the Hare Plan focused on the area we think of as the Civic Center today but, in fact, the plan also included a corridor running to the south which would include the old county courthouse, as well. A drawing of the contemplated NEW courthouse which would have been in the same place as the old one, was not included in the Hare drawing. Instead, the focus was on a new City Hall. The May 17, 1931, Oklahoman article which reported on the Hare Plan makes that clear:

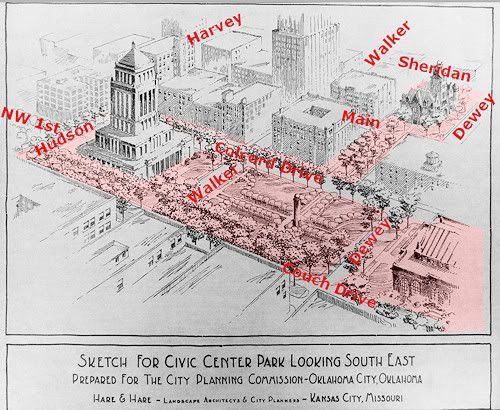

If the above drawing looks familiar, that’s because it is the same sketch found by Blair Humphreys when doing his research. Let’s have another look at the Hare & Hare sketch that Blair discovered with some added notes and color:

When I first looked at the original image, I presumed that the tall building was the concept forerunner of what is today’s Oklahoma County Courthouse. I was wrong. Instead, it presented an idea of what a new City Hall might be like, a tower and not the low-rise building which eventually came to be.

By piecing together various Oklahoman articles, it became clear that the 1931 Hare plan, if adopted, would include …

- A City Hall (and library) tower at the same location the current City Hall building is located

- A municipal auditorium at the same location that the Civic Center Music Hall is located today

- A park between those two buildings

- A pedestrian area running south to the old courthouse

- A new county courthouse to be constructed at the same location as the old courthouse

- An Oklahoma City law enforcement and jail structure to be built at an unspecified location

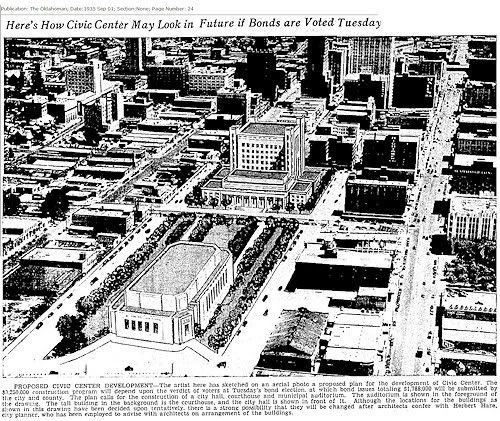

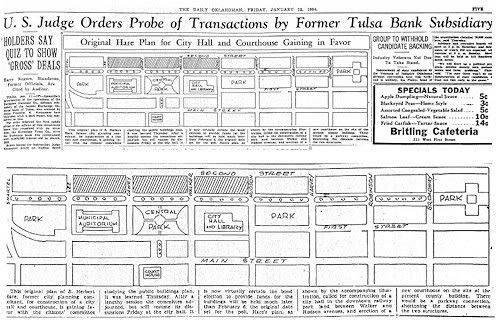

A drawing in the January 12, 1934, Oklahoman presents the overall layout more clearly …

Notice that to the right (east) of the proposed City Hall & Library another Park was proposed between Hudson and Harvey. Instead, that “park” space eventually was selected as the location for the new county courthouse. Likewise, the “park” show west of the municipal auditorium would become the home of Oklahoma City’s law enforcement and jail building.

By 1934, the part of the Hare Plan which called for a new county courthouse at its then existing location had fallen into disfavor as being inadequate in size and not the best location. In a January 29, 1934, Oklahoman article, Fred Suits, president of the Oklahoma County Bar Association, urged postponement of the February 20 bond votes (one on the city, one on the county, projects). In the article, he is reported as saying,

Needs of Oklahoma county have outgrown the present courthouse site. The growth of commercial and industrial enterprises around the courthouse renders the courthouse and the site unfit as a location for a new structure. The increased traffic in the zone makes it difficult in the summer to carry on business in the courthouse because of the noise.” * * * When the tax payers are being asked to vote bonds for a courthouse or a city hall, they are entitled to know first where the building is to be located, and second, whether there is good title to the land upon which the building is to be located.

Other controversies were unresolved … should the area contemplated for the City Hall instead be a city-county building … should there be two buildings, a city and county building side-by-side … could city and county offices co-exist in a combined structure without county government fearing that it may eventually be absorbed into the Oklahoma City Borg? In this, recall that the city, not the county, owned the land once occupied by the east/west railroad tracks which had bisected downtown Oklahoma City.

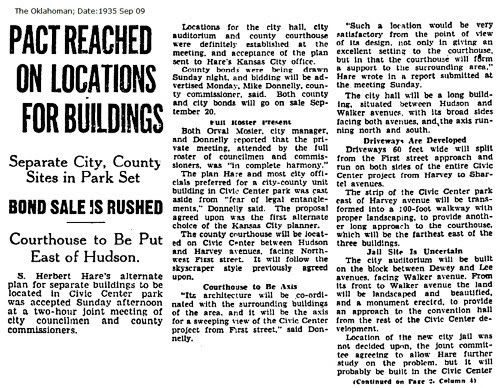

The bond voting did get put off. As late as January 1935, additional proposals were submitted, such as this one described in a January 20, 1935, Oklahoman article. Others were also submitted. Which plan? Which architect? Where located?

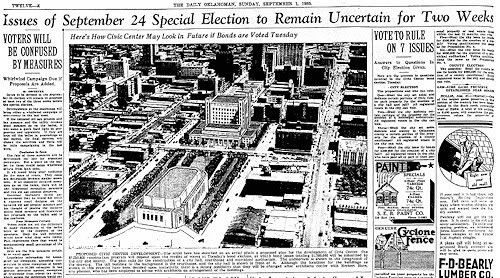

An election was scheduled for September 3, 1935, on the city and county bond proposals. By the time the vote rolled around, the concept of the Civic Center, at least as shown in the Oklahoman, was different than was contained in the original Hare Plan. In the September 1 article below, a preview of the Civic Center was shown:

Note that, in the above preview, a pair of buildings is shown in the space occupied by the City Hall building today. In the front (west side), a shorter City Hall building is shown with an entrance on Walker and immediately adjacent and east of the taller county courthouse building which faced Hudson.

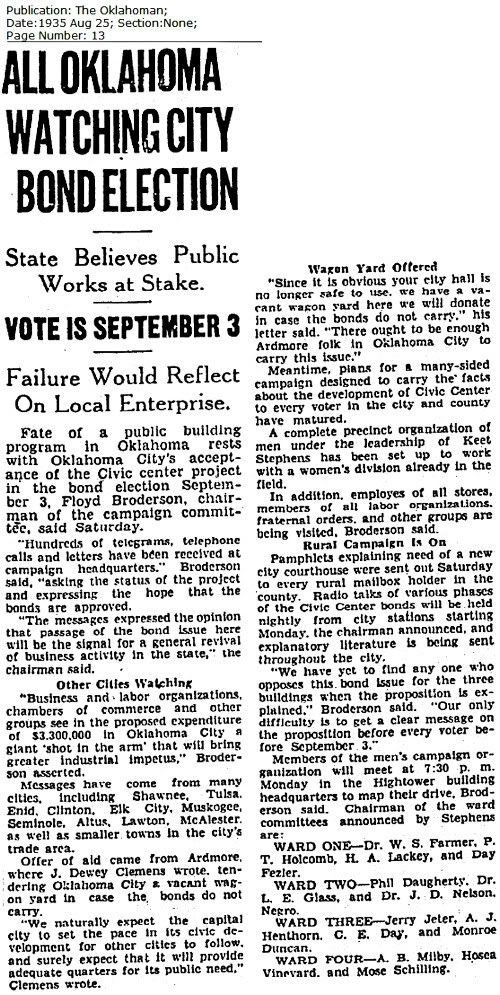

Interestingly, the Oklahoma City/County vote was of sufficient statewide interest for the Oklahoman to publish the following article on August 25:

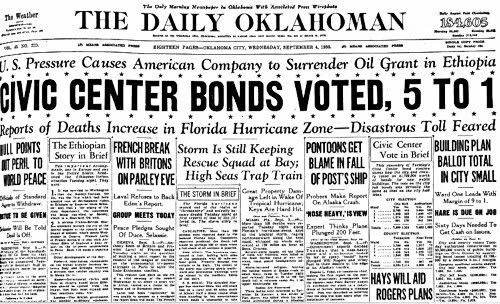

The September 3, 1935, vote carried by a 5-1 landslide.

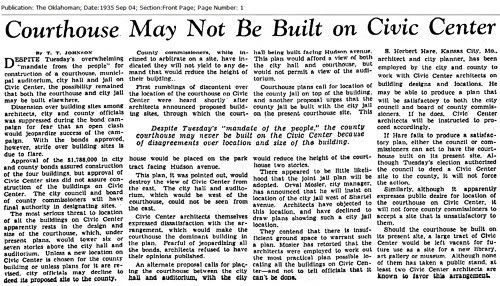

Why not? As the bond issue was drawn, details about what building was to be where and what such possible buildings would be were not described particularly and, in fact, had not been decided. On the same day that the Oklahoman reported the 5-1 vote on the bond elections, it also reported that the courthouse and/or city jail might not even be built in the Civic Center area:

So, many Oklahoma City/County voters may have then been wondering, “What’s the deal?” Remember what I said above … the city owned the property vacated by the railroad tracks, not the county. The above article says,

Dissension over building sites among architects, city and county officials was suppressed during the bond campaign for fear that an open clash would jeopardize success of the campaign. With the bonds approved, however, strife over building sites is due to flair.

The most serious threat to location of all the buildings on the Civic Center apparently rests in the design and size of the courthouse, which, under present plans, would tower six or seven stories above the city hall and auditorium. Unless a new location on Civic Center is chosen for the county building or unless plans for it are revised, city officials may decline to deed its proposed site to the county. ¶ County commissioners, while inclined to arbitrate on a site, have indicated they will not yield to any demand that would reduce the height of their building.

* * *

There appeared to be little likelihood that the joint jail plan will be adopted. Orval Mosier, city manager, has announced that he will insist on location of the city jail west of Shartel avenue. Architects have objected to this location, and have declined to draw plans showing such a city jail location.They contend that there is insufficient ground space to warrant such a plan. Mosier has retorted that the architects were employed to work out the most practical plan possible locating all the buildings on Civic Center — and not tell officials that it can’t be done.

So who would decide? For the county’s part, it apparently opted to submit the matter to Hare & Hare and abide its opinion in the matter.

However, the view of his which prevailed was to construct the county courthouse EAST of the City Hall building in an area described in his earlier plan as a “park” between Hudson and Harvey and in a design consistent with the style used in the city projects.

So, but for the placement of the city law enforcement and jail structure, the plans were finally set.

Lawsuits and More Lawsuits. Overlooked in this discussion so far is that the legal title to much of the property on which the Civic Center sits was uncertain and came to involve more than 100 lawsuits, one of which reached United States Supreme Court. This article won’t trace them fully but will give something of the flavor. The lawsuits began when Oklahoma City was conveyed title to the east/west railroad tracks owned by the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railway Company after city voters approved the 1927 bond election to finance the city’s acquisition of the property and make way for the Civic Center.

Rock Island itself was the successor in interest to the right-of-ways of the Choctaw Coal & Railway Co. which had acquired them in the first place from individual property owners in the late 1890s along both sides of the east/west tracks which bisected downtown. Many of those conveyances included reversion clauses which essentially provided that if the properties ceased to be used as a railroad the property interests would revert to the former owners (and, effectively, their successors in interest).

After Rock Island exchanged a quit claim deed to the area covered by the tracks for a big bucket of money paid for by Oklahoma City voters, who really owned good title to the land? A “quit claim deed” makes no promises of ownership or that the grantor’s title is good, it merely conveys whatever, if any, title that the grantor might or might not own.

While all of the discussion was going on over what the Civic Center should be like and what it should include, discussion was going on in the courts, as well. Doubtless, that fact was what the County Bar President alluded to in the January 29, 1934, article above wherein he was quoted as saying, “When the tax payers are being asked to vote bonds for a courthouse or a city hall, they are entitled to know first where the building is to be located, and second, whether there is good title to the land upon which the building is to be located.”

One such lawsuit had already been decided by the Oklahoma Supreme Court and the decision was favorable to the city. However, an October 15, 1935, Oklahoman article reported that the United States Supreme Court had just granted a petition for certiorari in which the high court agreed to review the Oklahoma Supreme Court decision. It is worth mentioning that the U.S. Supreme Court is not required to “accept certiorari” and review state supreme court decisions and that, more often than not, it declines to do so.

On March 3, 1936, the Oklahoman reported that the United States Supreme Court had decided against the city and the case was remanded to state courts to make new decisions consistent with the high court’s ruling which upheld the position of claimants having reversion clauses in their deeds. Other legal issues were left to be resolved by the Oklahoma Supreme Court on remand. Click here to read the complete Oklahoman article.

A February 3, 1937, Oklahoman article reports that, on remand, the Oklahoma Supreme Court had decided in favor of the private litigants but that it would be asked to reconsider its decision. The lengthy article noted that 99 similar cases were then pending against the city. Click here to read that article.

By the end of 1938, the city appeared to have resolved most of the legal hurdles and was out of the woods, so to speak, thus avoiding extensive condemnation proceedings which may have necessitated an additional bond election. A November 22, 1938, Oklahoman article reported that the city’s municipal counselor said that four-fifths of the related disputes “had been cleared,” whatever that means. Maybe that was so, but the Oklahoman’s archives reflect that this type of Civic Center litigation continued until as late as 1945 and that very often the city was unsuccessful and was required to effectively pay twice for the same parcel of land, once to Rock Island and once again to successful litigants.

I’ll close the “legal stuff” with one interesting claim — the claim of W.R. Ramsey (oilman and builder of the Ramsey Tower, City Place today). Turns out that he had made a $500 contribution in Charles Colcord’s fund raising drive associated with the city’s bond election to acquire the railroad properties from the Rock Island. Turns out that, he favoring the vote, he was deemed estopped (prevented) to dispute city’s title! The same defense was used against the claim of W.T. Hales (of Hales Building fame), a city financier. For being two-faced in the matter, they should be required to take the walk in Doug Dawgz Walk of Shame!

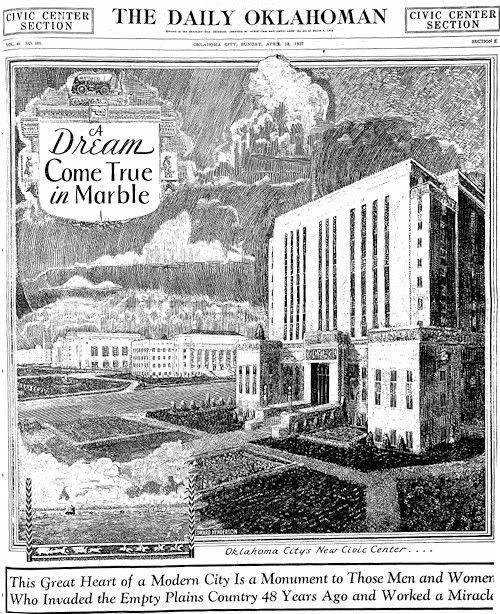

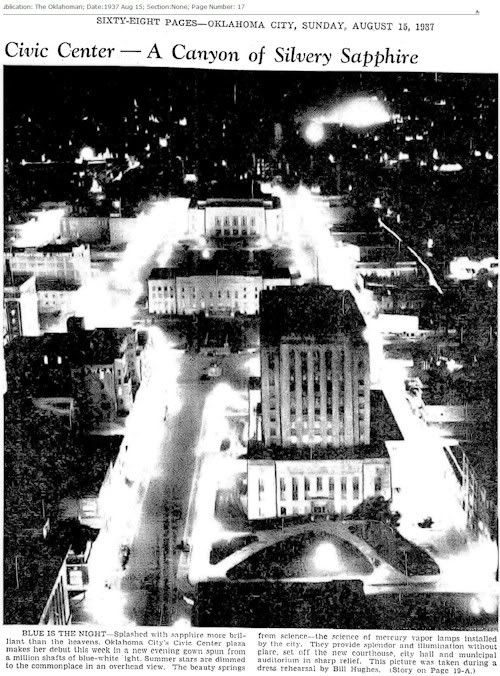

The Civic Center’s Grand Opening. We obviously know that, somehow, the buildings all got built. I’d be remiss if some discussion wasn’t given to the opening of the new facilities in 1937. The city and county were clearly proud of their new digs.

August 15, 1937

The Other Parts. Even though not commonly thought of as part of the “Civic Center” today, strictly speaking the law enforcement and jail facility west of Shartel and the parks from Hudson to Broadway were also part of the Civic Center plan. The photographs below show those areas.

and are credited to the Oklahoma Historical Society

Next 2 pics 1939-1940 looking east from Shartel

In 1939, Radio-cars and OKCPD east of Shartel

As noted by Ron Owens in his fine history of the Oklahoma City Police Department, Oklahoma Justice, at page 107:

The first police radios were one-way. Cars could receive messages but they couldn’t reply or ask for further information so the call-box routine remained as a standard procedure. By 1936, 40 radio-equipped scout cars were receiving 3,000 calls a month over station KGPH.

Park areas looking east from Hudson

to Robinson along Couch Drive in 1965

Last, recall that the “Civic Center” tract of land extended from Shartel to Broadway. At the east, immediately north of the Skirvin Hotel at 208 N. Broadway, a USO club was built during World War II to serve members of the armed forces, and the postcard below shows the name, “Civic Center USO Club, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma”. Once the war ended, it was converted to the home of the Service Center Community Chest Council of Social Welfare. That operation either closed or moved on by the mid-1950s, (part of it evolved into what is now United Way) and the last tenant appears to have been the campaign for a 1955 city bond issue. In the mid 1960s, the property was turned into a cabana and pool for the Skirvin Hotel.

POSTSCRIPT — what became of the old courthouse? Although the original 1931 Hare & Hare Plan called for a new courthouse to be erected upon the site of the old one, that just didn’t happen. County officials’ views were the same as those echoed by the County Bar President, above — the building location and size was inadequate to meet the county’s needs. The old courthouse building simply fell by the wayside in the above process and its preservation was not then seen as important. After the new courthouse was opened in 1938, the old one was used for various purposes. According to the 1st The Vanished Splendor book by Jim Edwards and Hal Ottaway (Abalache Book Shop Publishing Co. 1982), and in which book the old courthouse adorns the cover, on the copyright page below the copyright is this description:

COVER

Perhaps no other building symbolizes Oklahoma City more than the Oklahoma County Court House. Construction began on November 4, 1904, and was completed in 1906. It was designed by architects William A. Wells and his partner George Burlingof in a style designated as Massive Romanesque. No sooner had plans been announced and the plot of land acquired, that a controversy developed between the business interests on Main and Grand. Each street had influential spokesmen and each side wanted the Court House to face on its street. A compromise was finally reached and the building was placed so that it faced west on Dewey between Grand and Main. In reality this meant that few people actually used the front entrance, but opted for the preferred side and back entrances instead. Exterior walls were constructed of Indiana limestone with the interior floors of granite and the walls and stairways of Vermont marble. The city literally outgrew the building and quite soon after it was completed, governing agencies were forced to rent office space in buildings outside of the Court House. The County moved in 1938 to a new Court House that was built in the Civic Center complex. The old Court House building was used by the federal government to house a group of wartime agencies during World War II, but a fire in 1944 caused the building to be abandoned and boarded up. Demolition began late in 1950 and was completed the following year. The land was used for a time as a parking lot and later sold to the Holiday Inn Corporation for a downtown motel.

Actually, the city didn’t outgrow the building, the county did. But, as the Vanished Spendor authors said, the building suffered a serious fire in 1944 and apparently that was that building’s end of the road.

After the fire, repairs were never made and the building just sat there, dilapidated and crumbling. Some discussion occurred about the property becoming the site of the city library (click here for an April 2, 1946, Oklahoman article) but that didn’t happen. Litigation was associated with this property, also — the deed to the county contained a reversion clause which I’ll not describe more particularly. After decision generally favorable to Clarence O. Russell against the county in U.S. District Court by Judge Stephen Chandler, the 10th Circuit Court reversed and in 1949 title to the property was clear in the county’s name. The May 7, 1949, article below gives some description of that and presents recollections of then Court Clerk Cliff Meyers as he walked through the charred remains of the building.

After the fire, repairs were never made and the building just sat there, dilapidated and crumbling. Some discussion occurred about the property becoming the site of the city library (click here for an April 2, 1946, Oklahoman article) but that didn’t happen. Litigation was associated with this property, also — the deed to the county contained a reversion clause which I’ll not describe more particularly. After decision generally favorable to Clarence O. Russell against the county in U.S. District Court by Judge Stephen Chandler, the 10th Circuit Court reversed and in 1949 title to the property was clear in the county’s name. The May 7, 1949, article below gives some description of that and presents recollections of then Court Clerk Cliff Meyers as he walked through the charred remains of the building.

The city was interested in buying the property but made no offer. The property appraised at $270,000 and was sold to the highest bidders, C.R. Anthony, B.D. Eddie, and L.A. Macklanburg, in December 1949 for $328,000. By the time last of the three articles shown below was written, the courthouse building had been razed and became a parking lot:

Eventually, the west part of the property eventually became the site of the Holiday Inn and its parking lot in 1964 — for more about that and the present owner, see my downtown hotels article — and the east part south of the Montgomery (formerly Montgomery Wards) became the Walker parking garage: