Even though Oklahoma City skirted the generally defined edge of the Dust Bowl and that the “event” is more an “Oklahoma” than an “Oklahoma City” topic, it would be wrong not to include it as part of Oklahoma City history. Even though its impact more directly hit western Oklahoma, particularly the northwest, the impact of the Dust Bowl was certainly felt in Oklahoma City and, in a broader sense, the general “label” which many in and out of Oklahoma City came to have if they are from Oklahoma — was born — “Okies.”

The National Weather Service lists the Dust Bowl as the 1st of Oklahoma’s “Top Ten” weather events of the 20th Century:

1. Dust Bowl – Early and Mid 1930s. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s ranks also among the most significant events of the century nationally, by literally changing the face of the Great Plains. Extreme heat and drought, especially in 1934 and 1936, with the all-time record high of 113°F set at Oklahoma City in August 1936. “Black Sunday” was the near the height of the Dust Bowl, with accounts of giant clouds of dust descending on Hooker, Oklahoma on April 14, 1935.

From Wikipedia comes this brief description:

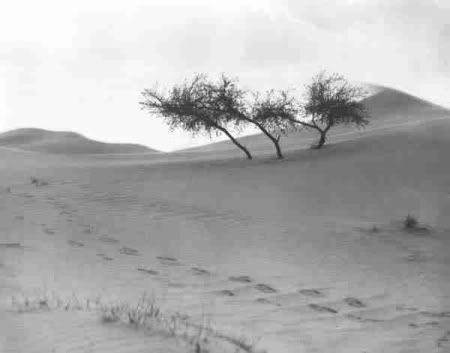

The Dust Bowl, also known as the “Dirty Thirties”, was a series of dust storms caused by a massive drought and decades of inappropriate farming techniques that began in 1930 and lasted until 1941. This ecological disaster caused a mass exodus from the Oklahoma Panhandle region and also the surrounding Great Plains. Around 300,000 to 400,000 Americans were displaced. Topsoil across millions of acres was blown away because the indigenous sod had been broken for wheat farming and the vast herds of buffalo were no longer fertilizing the rest of the native grasses.

It is well known that there was economic instability in agriculture during the 1920s, due to overproduction following World War I. National and international market forces during the war had caused farmers to push the agricultural frontier beyond its natural limits. Increasingly, marginal land that would now be considered unsuitable for use was developed to capture profits from the war. After the land had been stripped of its natural vegetation, the ecological balance of the plains was destroyed, leaving nothing to hold the soil when the rains dried up and the winds came in the 1930s.

With their crops ruined, lands barren and dry, and homes foreclosed for unpayable debts, thousands of farm families loaded their belongings into beat-up Fords and followed Route 66 to California. Many of the displaced were from Oklahoma, where 15% of the state’s population left. The migrants were called “Okies,” whether or not they were from Oklahoma. High end estimates for the number of displaced Americans are as high as 2.5 million, but the lower value of 300,000 to 400,000 [Oklahomans] is more probable based upon the 2.3 million population of Oklahoma at the time. [Emphasis supplied]

John Steinbeck’s classic novel, The Grapes of Wrath, tells part of the story. Whether living in or out of the state, Oklahomans wherever located have ever since been labled, “OKIES”. Even though, today, many of us who live here wear that cheap-shot title as a badge of honor, it was not always so.

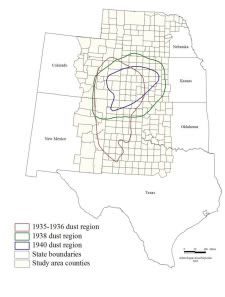

The Dust Bowl was not just an Oklahoma “event” – it covered the all of Great Plains states, generally, and Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado, as well. All of those migrating west, whether from the Dakotas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, wherever, became known as “Okies.” See this Nebraska website.

This image from an article by Geoff Cunfer at eh.net/encyclopedia shows the most concentrated Dust Bowl area … click on the pic for a larger view …

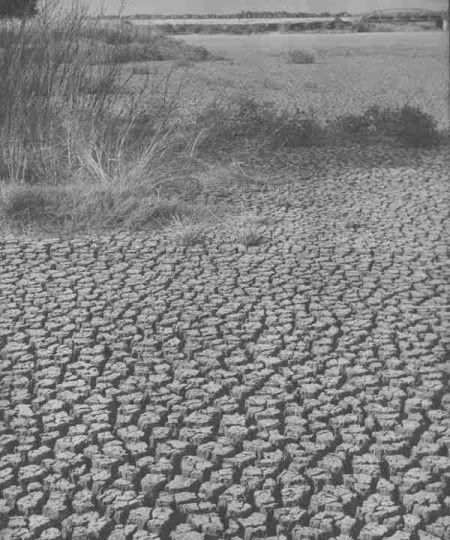

These images from an article by Article by Jana Hausburg at the Okc Metro Area website show some of the effects in the western part of Oklahoma County in the mid-1930s, of course, part of Oklahoma City today … click on a pic below for a larger image …

Lake Overholser Looking North to US 66 In 1935

Notice the US 66 Bridge, NW 39th, at the Top

The article says,

Although Oklahoma County was not in the region known as the Dust Bowl, dry conditions upriver produced low water levels and parched earth like this at Lake Overholser [above].

An article in the National Journal says that, “Then in the 1930s came a decade of bust–or dust–as soil loosened by erosion was whipped into giant swirling clouds: The Dust Bowl. ‘On a single day, I heard, 50 million tons of soil were blown away,’ John Gunther reported later. ‘People sat in Oklahoma City, with the sky invisible for three days in a row, holding dust masks over their faces and wet towels to protect their mouths at night, while the farms blew by.’ Okies headed in droves west on U.S. 66 to the green land of California, and Oklahoma’s population sank to 2.3 million in 1940 and 2.2 million in 1950, not to reach its 1930 level again until 1970.”

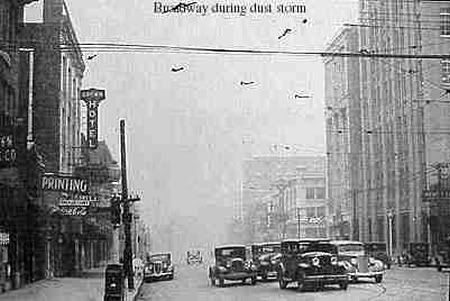

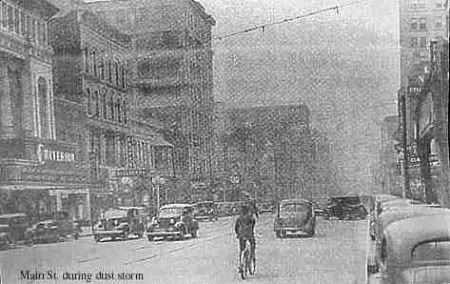

Images from the County Assessor’s Photo Gallery show a few images of downtown during this time …

On Main

While that doesn’t look good, the western parts of the state experienced what can only be described as surreal horror. One particular day, April 14, 1935, is known as “Black Sunday” throughout all of the central plains. Many believed the world was coming to an end. See www.ptsi.net and www.bookrags.com, for examples. At www.scholastic.com the day is described:

Cyclonic winds traveling at speeds up to 100 miles per hour rolled out of the Dakotas and traveled quickly across Nebraska, Kansas, eastern Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico. Dirt clouds churned 20,000 feet into the air and created a thousand-mile-wide duster.

Click on any image below for a closer look.

Leaving For Points West

A Plague of Locusts. Unlike those recently extended compassion and welcome in the post-New Orleans Katrina exodus, Okies were not greeted with “open arms.” In www.theroadwanderer.net, it is said,

The plight of the Oakies became a part of the Route 66 story, the legend of the road. In 1934, Los Angeles police stationed themselves at the Arizona border in order to check the wave of dust bowlers. The police held all immigrants at the state line, allowing only a few across at a time and turning many back. This checkpoint didn’t last, however, and emigration on Route 66 continued through the 1930s. By 1939, the migration had reached epic proportions, and Californians reacted with fear and anger. One California grower put it in the following way: “This isn’t a migration—its and invasion! They’re worse than a plague of locusts!”

An article at www.okhistory.org reads,

In 1937 California passed an “Anti-Okie Law” making it a misdemeanor to “bring or assist in bringing” any indigent person into that state. The law was later declared unconstitutional, but the bias remained. There are those who, like Will Rogers, believed that the migration of “Okies” to California raised the intellectual level of both states.

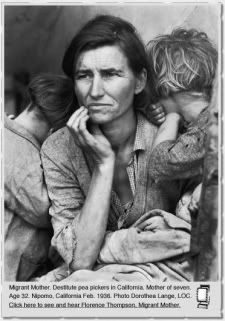

The plight of Okies has been been well chronicled by many, including renowned photographer Dorthea Lange. From www.theroadwanderer.net:

One of the most haunting images to come out of the dark days of the dust bowl and great depression is this photograph by Dorthea Lange. She was commissioned by the Farm Security Administratrion to chronicle the plight of the displaced farmers during the dust bowl. Dorthea found this migrant mother on the road in 1936. The mother’s eyes tell the viewer all he/she needs to know. The expression of fear and and hoplessness are reflected in her eyes as she appears to be looking down the road to a very uncertain future. This photograph became an American icon of the dust bowl days and brought an awareness of the struggles of the “Okies” by putting a human face on this tragedy. *** An estimated 210,000 emigrants came to California during the dust bowl, many of whom were forced to return home after failing to locate employment in the Golden State. Only approximately 16,000 remained.

And there were many, many others …

Maybe we’ll return the favor when western California drops off into the Pacific? No, we won’t … that’s not what Okies would do!

A 22 minute NPR audio file of interviews of Okies in 1940 by Charles Todd is here. According to the NPR site, “1940, Charles Todd was hired by the Library of Congress to visit the federal camps where many of these migrants lived, to create an audio oral history of their stories, and to document the success of the camp program to the Roosevelt administration back in Washington. Todd carried a 50-pound Presto recorder from camp to camp that summer, interviewing the migrant workers.”