Certainly all Oklahoma Citians are well acquainted with the excellently developing “Asian District” around the vicinity of Northwest 23rd and Classen … how could one not have noticed the markers on street signs from Classen as far north as N.W. 36th Street:

The area continues to expand, such as with this in-process development around N.W. 23rd and Western, the upcoming Sun Moon Plaza:

But, all of that is the subject of two later posts … Asian District Today … The Story and Asian District Today … The Pics.

This post is about the much older Chinese Underground in downtown Oklahoma City.

An underground Chinatown once existed in the vicinity of Main – Sheridan – Broadway -Robinson but the extent of which is unknown (as far as I’m aware). Artifacts were discovered when excavation occurred for the Myriad Convention Center in 1969.

According to Terry L. Griffith, Images of America: Oklahoma City, Statehood to 1930 (Arcadia Publishing 2000), p. 119:

The Underground, c. 1925. This view of the Bassett Block at Main and Broadway shows the entrance to the underground Chinatown. Bill Skirvin would sit in his hotel lobby and watch the Chinese residents enter the alleys behind the Bassett Building and walk down the steps leading to their very private world.

A fascinating article on the Chinese Underground and Oklahoma City resident Willie Hong written by Larry Johnson appears at the Okc Metropolitan Library System. (Once there, you may need to click your refresh button for the target page to load.) Excerpts from that article follow:

In April, 1969, former Oklahoma City mayor George Shirk, his sister, and two friends entered an unobtrusive door on the side of a condemned building at 12 S. Robinson. Leaving daylight and the bustle and noise of downtown traffic behind, they descended into Oklahoma City legend.

Work was scheduled to begin soon on a major urban renewal project (the Myriad Convention Center) and Shirk had been tipped off that beneath the rows of condemned buildings along South Robinson a subterranean chamber had been discovered. Armed with flashlights and old-fashioned Okie intrepidity, the quartet explored a vast subterranean chamber which appeared to be the legendary underground Chinese city that Oklahoma Cityans had always heard about, but no one seemed to remember ever having actually seen. For decades parents kept their children in check by telling them if they didn’t behave the Chinese would take them into the tunnels and they’d disappear; generations of high school pranksters tried to locate the underground city; and even the pointy-heads from Norman came up to document the phenomenon, but no one could ever find a way in – if it existed at all.

But the Shirk expedition found a way in and discovered large community rooms 25 feet wide with passageways leading to 4×6 foot sleeping chambers. A kitchen area was found with an intact stove. They also found Chinese writing all over the walls including one sign near a sturdy door with a window in it. No one present spoke Chinese, but it was later translated by a restaurant employee who said it read “Come Gamble”. It was not recorded how far below the surface they explored, but they did discover two levels below the buildings’ basement level, so the underground city was quite deep.

As soon as the discovery was reported in the Daily Oklahoman, long-time residents rose up and submitted their own anecdotes. Several people who had lived in the rooming houses in the area said they remembered that Chinese people always lived in the basement apartments and could access their underground areas from there. Some remember the Chinese growing bean sprouts and mushrooms underground. One former neighbor recalled that one day the Chinese were simply gone – that was around 1948. One former resident, bookseller James Neill Northe, had befriended some of his Chinese neighbors and he recalled that he was invited in as the last Chinese were leaving. He saw Fan Tan (a Chinese gambling game) markers and a Buddhist temple. Another man who had been a landlord in the area was told that there was a third level which contained a Buddhist temple and a burial area. Although Shirk’s expedition didn’t find this third level, it is likely true that such an area existed.

To most of us the idea of a Chinese city underground (or any city underground) is quite exotic. However, placed in the proper context, it really isn’t surprising at all that such a place existed. Chinese immigration to America began with the California Gold Rush in 1848. Life in China had become chaotic after its forced ‘opening’ to Western trade caused the corrupt and repressive Manchu dynasty to collapse. Like nearly every other immigrant group coming to America, the Chinese were lured by the promise of a better life; thousands came seeking fortune, but few achieved it. It was in the 1850’s as planning and implementation of the Trans-Continental Railroad began that hundreds of thousands of Chinese began to flow through San Francisco into the inter-mountain west. Because building the railroad would be labor intensive, the line builders needed a huge workforce and the Chinese quickly filled that role. Life was hard for these workers and because they were often temperamentally meek and hard-working, they were willing to do almost any job and consequently did not gain the respect of broader American society.

* * *

By the 1880’s the railroads had been built and the huge Chinese labor force was no longer needed. Chinese workers began to move into farming and manufacturing work. All the while, thousands of Chinese immigrants continued to stream into San Francisco – two million by 1880. Leaders in Western states began to fear that the Chinese would take the jobs of already established workers, so they began a campaign to limit or stop Chinese immigration. The result was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which stopped virtually all Chinese immigration. To make matters worse, all Chinese who were caught in the United States without proper ‘paperwork’ (which was virtually all of them) would be immediately deported. There were other similar laws enacted such as an act which forbade Chinese men from marrying Caucasian women.All of these factors served to literally drive most Chinese communities underground because of the dangers of living amid mainstream society. The Chinese lived under most cities in the west with San Francisco obviously having the most developed underground network. Many other places from Seattle to Moose Jaw to Boise had underground cities, and Deadwood, South Dakota has even made a tourist attraction of their existing underground city. So, although it’s still exotic, it’s no surprise that Oklahoma City had an underground city as well.

No one knows for sure, but the first Chinese immigrant probably came to Oklahoma City with the construction of the railroad or at the time of the Land Run. We do know that when the first city directory was published in 1890, there were five Chinese listed (Sam Chong, Hong Kee, Ming Lee, Sing Lee, and Wah Hop). These enterprising men most likely had come to the United States before the Exclusion Act and had been able to secure resident status. It is safe to assume that there were more than just these five Chinese in the city. However, later census records for 1900, 1910, and 1920 consistently list only a handful of Chinese in Oklahoma City.

As important as the Shirk expedition was, its discovery merely serves to confirm for later generations that such a place existed – it was unable to really illustrate for us what life was like inside the subterranean town. Few non-Chinese ever ventured into the catacombs, but we do have some records of people who did. In 1921 the Oklahoma Department of Health began a campaign to improve sanitation and living conditions in the state’s boarding houses, restaurants, grocery stores and the like. So in January, state health inspectors swarmed over eighty locations in Oklahoma City – six inspectors and one sheriff went underground. The inspectors were doubly amazed when they entered the subterranean village via a blue door in the alley off Robinson between Grand (Sheridan) and California – they did not expect the underground area to be so extensive nor did they expect it to be so clean.

The inspectors found several caverns of sleeping rooms extending from a central living room and kitchen and they reported that all the passageways were expertly dug and quite securely designed. Apparently two men shared a hollowed out room with dirt walls and floor and slept on grass mats placed on the floor. There were enough of these rooms to house an estimated 200 people. One inspector reported that the area seemed well-suited for three things – sleeping, eating, and gambling. Inspectors assured the Chinese inside that they weren’t concerned with gambling, just safety, and went about their business. At first they had assumed there were only two levels, but when they were all-too-eagerly greeted by men at the far end of the system, they realized there must’ve been a third level below which allowed someone to run ahead and alert the other residents. Finally, despite a raised eyebrow over the crate of live chickens in the kitchen, the inspectors confiscated two dirty blankets and gave the entire community a glowing, clean bill of health. By contrast, several above-ground restaurants and rooming houses were cited or closed down due to poor sanitation.

The fascinating thing about the inspectors’ report is that it confirms much of the ‘archaeological’ evidence unearthed by the Shirk expedition as well as the anecdotes shared by longtime Oklahoma City residents. The report also suggests that conditions in Oklahoma City’s Chinatown were much milder than that of other, larger cities in the west. The inspectors were accompanied by a policeman and none in attendance seemed overly concerned about either the level of gambling or the presence of opium dens (the inspectors apparently did not see any of the tell-tale signs of opium use).

* * *

Sometime shortly after World War II, the underground Chinese colony was abandoned. No one is really sure why. The Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, and even though the Act was loosely and infrequently enforced in Oklahoma, its repeal erased any doubt that the Chinese were now able to live freely above ground and take part in the society of which most of them had spent the majority of their lives on the fringe. Many of them may have gone back to China to fight in the civil war while others simply wove their lives into the fabric of Oklahoma City life. The various urban renewal projects in the area have probably removed any physical evidence of the old Chinese city, but there are still underground passages in Oklahoma City. Some believe the tunnels that once connected the many movie theatres on Main Street and allowed runners to shuttle film reels back and forth are still intact.

A good bit of Larry Johnson’s article, not covered in this post, focuses on one who was called, “The Mayor of Chinatown”, Willie Hong. Check out Larry Johnson’s article for more about that.

During excavation in 1969 for the Myriad Convention center, workers found traces of the ruins, as noted in Larry Johnson’s article. Former Mayor George Shirk’s venture into this piece of Oklahoma City was a front page Daily Oklahoman story in its Sunday, April 9, 1969, edition. The article’s headline reads, “Hidden Chinese City? Maybe So, Maybe No”.

The article begins,

Tales of a long-hidden “Chinese city” beneath downtown Oklahoma City were dusted off Tuesday as the result of an unusual expedition.

For years, children were cautioned to avoid certain downtown streets for fear “the Chinamen” would get them.

* * *

Wild stories persisted right up to Tuesday that an entire city of Chinese was living beneath Oklahoma City with its own government, its own businesses and its own code of conduct.

* * *

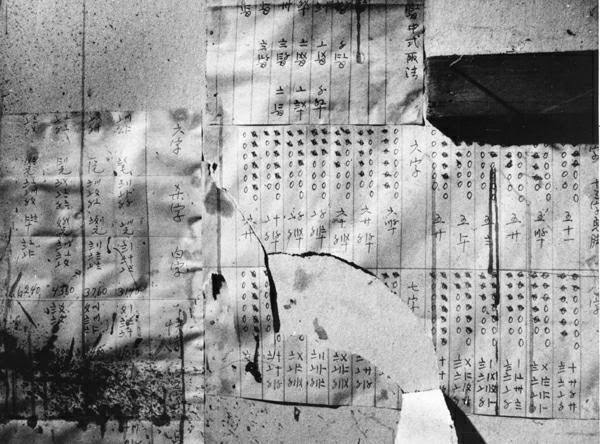

Connecting rooms of various sizes – some with Chinese writing on their walls – were found under the now-vacant shops of S. Robinson, just south of the Commerce Exchange Building.

The Commerce Exchange Building was built in the mid 1920s, and was located at the southeast corner of Grand (now Sheridan) and Robinson. From today’s Colcord Hotel, then the Colcord Building, it was located diagonally southeast from the Colcord across the Sheridan and Robinson intersection and sat on space presently occupied by the western part of today’s Cox Convention Center.

The Oklahoman article shows an example of the writings on the walls below and south of the above building:

The Oklahoman article continues …

Yellowing newspaper editorial cartoons about China were pasted to the wall of one large room which appeared to have been a living area.

* * *

A corner of a large L-shaped room, which was 24 feet long, contained a sink and an old stove, apparently used in connection with a laundry.Click the image for a larger pic

Entrance to the strange labyrinth was through a scarred white door in the alley behind the Commerce Exchange Building on S Robinson.

* * *

Through a narrow passageway about 25 feet south of the entrance and near Robinson street ws another 25-foot wide area which also had been cut up into smaller rooms.Dimensions of the total area were 50 feet wide and 140 feet deep, Shirk said.

* * *

A second outside entrance was discovered on S. Robinson next to the business at 12 S Robinson. Shirk guessed that similar rooms exist under the remainder of the block, but no access to them was found.The block of businesses extends another 150 feet south of the south wall of the two areas explored.

Whoever lived in the underground rooms did not see much light of the sun. Light bulbs hung from the ceiling of every room, offering the only illumination. The cement floors were damp and the brick walls were cool to the touch.

According to Oklahoma City directories, several of the businesses over the rooms were operated by Chinese from 1910 through 1928.

The 1969 article’s report sounds like a pretty “good find” to me, but other archived Oklahoman articles appear to me to be inconsistent about the existence or extent of the Chinese Underground. For example, a June 8, 1984 Oklahoman article captioned, “Chinese Seek Roots Ansewers in City,” tells the tale of Roger Eng who ventured to Oklahoma City from Los Altos, California, to trace his family’s ancestoral roots. He was looking for the Kingman Cafe, once located at 227 Grand (Sheridan). The article notes,

In 1911, the cafe was a few doors west of the old Overholser Opera House [ed note: immediately west of the Colcord].

* * *

Rumors of the existence of a Chinese underground city in earlier day Oklahoma City persist although there are few reliable reports. Urban renewal demolitions in the area revealed a few basements and some Chinese writing but little else.

But, another Oklahoman article, May 9, 1976, called, “Where Will All the Winos Go?” (which refelected upon the demolition of “Herman Vestal’s Place” at 225 W. Sheridan), said this:

There was never any serious trouble and few fights in Vestal’s. “You only run this kind of place one way, and that’s to be firm and don’t play no favorites,” the owner said.

There are glass bricks still inlaid in the front sidewalk. They transmit light down into the basement which reportedly onced housed a kitchen for the famed Chinese underground. The subterranean system flourished in the 1920s and ’30s, a network of tunnels and rooms connecting a number of downtown Chinese laundries and restaurants. [Emphasis supplied]

The Oklahoman’s writers need to check their own archives and get their act straight!

Also of very significant interest is a paper (or papers) written by Xiaobing Li, professor of history and associate director of the Western Pacific Institute at the University of Central Oklahoma, and who served in the People’s Liberation Army in China, and who has written on the topic. He presented his paper, Buried Memories: Underground Chinatown in Oklahoma City,1900-1920, at the 2004 Annual Conference of the Western History Association and another, Chinese Immigrants’ Experience in Oklahoma City, 1900-20, at the 2003 meeting of the American Historical Association. According to the Newsletter of Chinese Historians in the United States, Inc. (Spring 2003):

LI Xiaobing (University of Central Oklahoma)’s study of the Chinese experience in Oklahoma and Ling Z. ARENSON (DePaul University)’s study on the Chinese communities in Chicago constitute departures from the much studied major Chinese settlements on the East and West Coasts. LI Xiaobing discusses the “underground Chinatown” in Oklahoma City. This Chinese community, discovered in 1969, was under five Chinese business shops in the downtown area. It was said to be about a mile long, covering two blocks. [Emphasis suppled] About 100 to 150 Chinese lived in the basements in this underground Chinese community between 1900 and 1930. By discussing this little known Chinese experience in Oklahoma, Li has argued that although the labor shortage, coupled with a lower level of prejudice and racial discrimination in Oklahoma, especially in the Indian Territory, drew a small number of Chinese from the West Coast as early as the 1880s, this Oklahoma advantage had its limitations. As early as 1890s, constrained by the limited possibility of economic advancement in the Indian Territory, more and more Chinese moved to Oklahoma City, where they lived in basements under Chinese stores and engaged in service occupations, primarily hand laundries and restaurants, as did their counterparts elsewhere. Some of them were believed to have died and were buried there, near where they had lived. Both metaphorically and factually, this underground world was powerful evidence of the wide spread hostility against Chinese during the Exclusion era. Li’s study has surely added a new regional and spatial dimension to our understanding of the drudgery and hardship Chinese immigrants had to undergo during the Exclusion era (1882-1943).

I’ve got to see if I can get a copy of the UCO professor’s paper one of these days!