May 4, 2009, note: Deep Deuce history is considerably expanded in a 2009 series of 30-40 articles contained in The Ultimate Deep Deuce Collection.

Note: The original post of this article was accidentally deleted when re-doing my “2006 Index” a couple of days ago. Thanks to Google’s “cashed” feature, it was able to be reconstructed pretty much like it was, although the article has also been revised as of today, December 5, 2006. The map and text as to Avery AME Chapel Church was corrected on September 7, 2007, to reflect the correct location (NW corner of NE 1st & Geary, not NE 1st & Stiles). Some new pictures and text was added on September 28, 2007.

A “social backdrop” for why Deep Deuce came to be is in my 1st post, Deep Deuce Prologue. A 3rd Deep Deuce post, Famous Deep Deucians, describes some famous Deep Deuce people. This post explores the physical buildings of the Deep Deuce that existed from the 1900’s into the ’40s and early 1950’s. The next will give more particular description of some of its people.

The map below gives a frame of reference, showing locations of the described in this post. The area originally known as “Deep Second”, now as “Deep Deuce”, is generally east of the north/south railroad tracks, west of I-235, south of NE 4th, north of the railroad which is the northern border of Bricktown – but note that the I-235 boundary is artificial and that the area extended further east but to a point that I do not know. I’ve also shown Douglass School in the map because of its impact upon Deep Deuce people, coming in part 3, even though it was not in Deep Deuce, properly speaking.

A nice aerial view of the Deep Deuce area appears in William D. Welge’s Oklahoma City Rediscovered (Arcadia Publishing 2007). This image appears to have been taken by the same photographer and from the same vantage point (top of the Skirvin Hotel) as was a companion image in Trains Part 3 but just turned a bit more toward the Deep Deuce area. Several Deep Deuce building are prominent in this image.

THE HISTORICAL BACKDROP

Why is this small slice of near-downtown Oklahoma City important? Aside from racial issues which necessitated the existence of a “separate” African-American “commercial and entertainment” area in the 1st place, described previously, this small area generated some of the most prominent Oklahoma Citians in the music and literature fields that our city has known, as well as providing “a place to go” for the then-disenfranchised Black citizens of our community. More, the African-American slice of Oklahoma City population has always been substantial, even though not all of it was located in the Deep Deuce area. For example, in 1910, Oklahoma City’s population was 64,205 (87th in the country) according to official census figures, of whom more than 7,000 of it were Black, according to Dr. Bob L. Blackburn’s fine article.

In his article, Dr. Blackburn provides this description:

From 1889 to the 1930s Bricktown was a battleground for social justice and the birthplace of cultural diversity in Oklahoma City.

It began when some of the first 200 African-Americans attracted by the land run settled in Sandtown, located along the north bank of the river east of the Santa Fe tracks. From there, the black community grew northward as jobs were created and new waves of immigrants arrived looking for a piece of the promised land. * * *

By 1915 the all-black residential community ringed the commercial district of brick buildings and stretched from the river on the south to First Street on the north and as far east as the 1000 block on Third Street.

Faced with this expansion of black families into formerly white neighborhoods, the Oklahoma City Council passed a segregation ordinance that would in effect prevent blacks from buying or moving into houses north of Second Street. Even after the United States Supreme Court declared that ordinance unconstitutional in 1916, de facto segregation kept the wall intact, making Second Street a symbolic battleline in the fight against racial injustice.

Additional description comes from an article by Kristin Winch describing a Governor’s Gallery exhibit, Ron Tarver, Deep Deuce & Beyond:

Beneath the gleaming modern facades and upscale apartments along West 2nd Street, and the abandoned homes and weed infested lots to the east, lay the remnants of what was, in its heyday, one of the most successful African-American business districts in the country.

“The 2.” “The Deuce.” “Deep Deuce.” Akin to Harlem of the 1930’s – in spirit, if not in scope – Deep Deuce spawned such legendary figures as jazz guitarist Charlie Christian, “blues shouter” Jimmy Rushing, and internationally acclaimed writer, Ralph Ellison. Deep Deuce attracted African-American professionals of every stripe. Roscoe Dunjee, Dr. Frederick Douglas Moon, Mrs. Lucy Tucker, Dr. William Lewis Haywood, Mary and Sydney Lyons. These doctors, educators, entrepreneurs, and activists came together, creating a critical mass that transformed 2nd Street and the surrounding neighborhood into a thriving corridor of Oklahoma City.

Deep Deuce produced the East India Toilet Goods and Manufacturing Company, the 2nd largest African-American hair product company in the world. The Deuce was home to the historic Aldridge Theatre, an African-American theatre that attracted some of the most prestigious talent in the country. Just beyond 2nd Street, Edwards Addition boasts the African-American owned and operated Edwards Memorial Hospital; in its era, the most well equipped state of the art hospital in Oklahoma.

An article in the Journal Record gives more background, looking back in time.

Re-evaluating Deep Deuce

Journal Record

Mar 1, 2001 by Max NicholsLittle by little, we are becoming more and more aware of the tremendous influence of Deep Deuce on the heritage of Oklahoma City.

The recent jazz series on Public Broadcasting System pointed out the contributions of Charlie Christian, Jimmy Rushing (Mr. Five-by- Five), the Blue Devils, Lester Young, Jay McShann and numerous other musicians who played in Deep Deuce and contributed heavily to the development of jazz. Ralph Ellison, who walked the streets of Deep Deuce and later wrote The Invisible Man, was quoted often in that series.

* * *

Why are most of us just now learning about the rich cultural heritage of this small area? The plain answer is that Deep Deuce, formerly known as Deep Second, was the business and entertainment center of the African-American community in Oklahoma City for more than half a century, and white people rarely went there or knew much about it.

* * *

As a result, little was written about the area until Director Anita Arnold of the Black Liberation Center and George Carney of Oklahoma State University came along. Arnold started researching the background of Charlie Christian and Deep Deuce for the Charlie Christian Jazz Festival, and Carney wrote about the contribution of jazz by Oklahomans in a 1994 edition of The Chronicles of Oklahoma. Their works are gradually seeping into the general population.Arnold interviewed people who worked and lived there while reading old copies of The Black Dispatch at the Ralph Ellison Library. [DL Note: the library is at 2000 NE 23rd, and go here for its website.]

She wrote three books, including The Legendary Times and Tales of Second Street and two on Christian, who elevated the electric guitar to national prominence — recording with Benny Goodman and Lionel Hampton. Because of her work, she was interviewed for two hours in the production of the Jazz series, and she supplied photos that were used.

Through Arnold’s work, we are finding out more and more about places such as the third-floor Slaughter’s Hall in the Slaughter Building, Ruby’s Grill, the Aldridge Theater and other Deep Deuce centers of business and entertainment. We are also learning about Deep Deuce entrepreneurs and people such as Zelia N. Page Breaux, a Douglass High School educator who taught Christian, Rushing and numerous others.

“I attended the old Douglass High School at NE 6th and High streets,” said Arnold, “and I graduated from the new Douglass High School. My parents used to take us to the Aldridge Theater (formerly at 303-305 NE Second) and pick us up after a movie.

“As a teenager, I worked at the Randolph Drug Store, which was located on the first floor of the Slaughter Building on the corner of NE 2nd and Stiles Ave. Integration already was beginning to affect Deep Deuce, with African Americans moving to other parts of the city, but we still had doctors and other professionals in Deep Deuce.”

Arnold reported that the Christian, Rushing and Whitby families were among the musical leaders of Oklahoma jazz history along with couples such as Juanita and Abe Bolar. Charlie Christian was the youngest of three boys of Clarence and Willa Mae Christian, who moved from Bonham, Texas, to Oklahoma City in 1918. The whole family played music. Charlie’s brother Edward became a music writer for the Black Dispatch. Their influence extended from the 1920s and 1930s to this day, including the outstanding blues played by D.C. Minner of Rentiesville.

* * *

The heritage of Deep Deuce, however, is much deeper than music. It goes back to the 1889 Land Run, when African-Americans settled in that area as well as in black towns across the state. Black entrepreneurs started hotels, shops, funeral homes and professional services.Among the pioneer entrepreneurs were Dr. W.L. Haywood, who started Utopia Hospital as the first hospital for blacks in Oklahoma City at 415 NE First St., and Roscoe Dungee, who started The Black Dispatch on E. Second St. in 1915. S.D. Lyons started the Lyons Hotel, and Dr. W.H. Slaughter owned the Slaughter Building and Slaughter’s Hall. James Simpson owned his own club, and Emma Burnett started her own business school.

Lyons was the father of Ruby Lyons, who owned Ruby’s Grill, which included the Lyons Den for special events and customers. Slaughter’s Hall became popular for club dances and other events. Zeilia Breaux was a co-owner of the Aldridge Theater, which hosted music and theater productions, vaudeville shows, touring companies and movies.

THE REMNANTS

Though most buildings have been replaced by upscale apartments and condos, some vestiges remain. This looks at some, not all, of those that do.

Calvary Baptist Church. This edifice, located at 300 N. Walnut, still stands, even though the signage “Calvary Baptist Church” (sadly) no longer marks its identification. Built in 1921, Calvary Baptist had a rich history, even a national significance, not only for its contributions to Oklahoma City but to the country. Martin Luther King wished to become the pastor there in 1954 before he came to national prominence, but he was apparently not invited because of his then youthful age.

In 1952, it hosted the 43rd Annual NAACP national convention. See Larry Johnson’s article at the Okc Metro Library website (you may have to click your “refresh” button/key after clicking the foregoing link).

Click on pic for a larger view

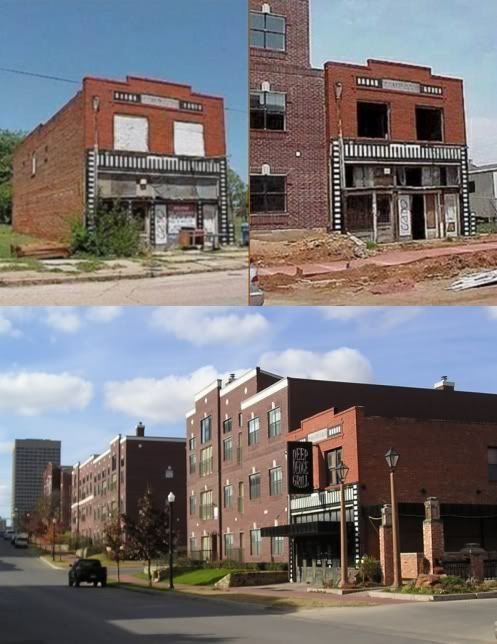

Deep Deuce Grill. This is the “Haywood Building”, purchased by Dr. W.L. Haywood in 1938, his clinic being on the 2nd floor. According to Key Magazine, he “relocated to Deep Deuce in the early 1900s. Haywood founded the first black hospital in Oklahoma City along with Dr. W.H. Slaughter, and he was the first African-American physician admitted to practice at University Hospital (now OU Medical Center). * * * In addition to practicing medicine, Haywood was an accomplished businessman and civil rights leader who regularly published newspaper columns promoting black businesses and railing against segregation in the Black Dispatch.” See the December 2005 on-line issue of Key Magazine for more.

As with the rest of this area, by the time that Deep Deuce’s vitality had passed, the building was but another dilapidated structure. The images below shows what it had become by 2000, the change which occured with adjoining properties in 2001, and, last, how it appears today. The first 2 images are from the Oklahoma County Assessor’s website and the last I took on November 25, 2006.

Deep Deuce Apartments Clubhouse. This building in the Deep Deuce Apartments is a restored original building but I don’t know which one …

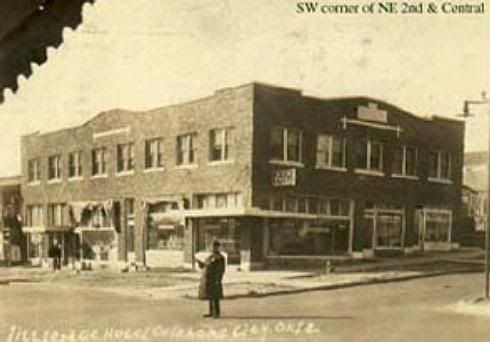

Unidentified Hotel. The County Assessor’s Deep Deuce Collection shows this photo, a hotel at the southwest corner of NE2nd and Central, but I can’t make out the name, given the photo quality. One was the Lyon’s Hotel, I don’t know the other’s name. A helpful contributor (John) at OkcTalk.com pointed out that this building, now renovated, still stands and serves as offices and condos.

According to a February 11, 2004, Oklahoman article, “When Deep Deuce was, it represented the heart”, 2 hotels were present along the street.

Since writing the original version of this post, I’ve been better educated by helpers like John and Dustbury’s CG Hill and I thank them! There are some other remnant Deep Deuce buildings, but I’ll stop with what I’ve said so far about that!

THINGS GONE

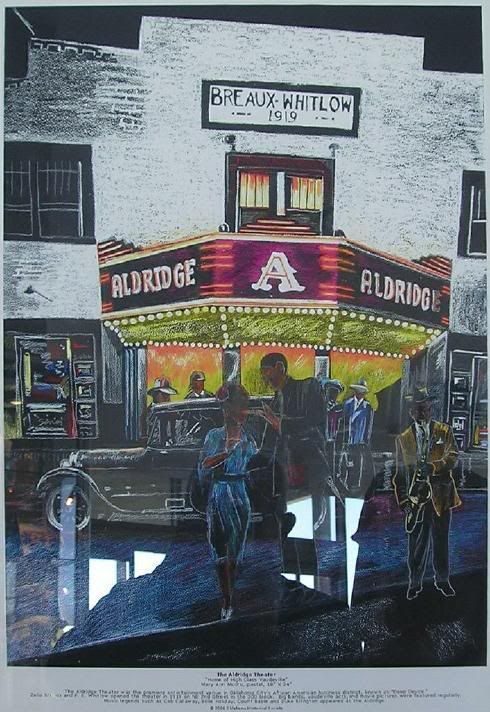

The Aldridge Theater. The Aldridge was at 303-305 N.E. 2nd, immediately west of where Deep Deuce Grill is today. On edit (9/28/2007), I’ve now located a photo of the Aldridge in addition to Mary Ann Moore’s painting – a print is available at the Oklahoma History – included in the original post. Both appear below.

Credit Mary Ann Moore & the Oklahoma Historical Society

Owned by Zelia Breaux and F.E. Withrow, the Aldridge opened in 1919. The small print at the bottom of the above reads, “Big bands, vaudeville acts, and movie pictures were featured regularly. Music legends such as Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday, Count Basie and Duke Ellington appeared at the Aldridge.” Zelia Breaux receives prominent discussion in Part 3 of this series.

In the picture below, the “Now Showing” plackards include a short subject, “Rocky Marciano v. Roland LaStarza” world championship fight pictures … a mini-movie that was released in September 1953 … and the main attraction, “A Perilous Journey,” released in April 1953 … so the image below must be sometime around September-December 1953.

Slaughter Building. Located at the northwest corner of NE 2nd and Stiles, this “mixed use” building housed a drug store and soda fountain in the 1st floor, professional offices (lawyers, dentists, doctors … like its owner, W.H. Slaughter) in the 2nd, and, in the top floor, a place for music and dancing which was called, “Slaughter’s Hall.” I wasn’t able to find a great pic, but the one below shows the 3 story building.

Click on pic for a larger view

Note: “123” is not part of the address, only the “East 2nd St.” part is.

It was recounted by Ralph Waldo Ellison (who as a child was a soda jerk in the drug store), that,

When we were still too young to attend night dances, but yet old enough to gather beneath the corner street lamp on summer evenings, anyone might halt the conversation to exclaim, “Listen, they’re raising hell down at Slaughter’s Hall,” and we’d turn our heads westward to hear Jimmy’s voice soar up the hill and down, as pure and as miraculously unhindered by distance and earthbound things as is the body in youthful dreams of flying.” – from “Shadow and Act,” a collection of essays by Ralph Ellison.

See Deep Second Still Lives In Dreams for more.

Here’s a look at that building in conjunction with a 1942 Wilson & Co. parade:

Click on pic for a larger view

The Black Dispatch. Roscoe Dunjee established this excellent weekly newspaper either in 1914 or 1915 (souces vary). The fine Dustbury archives, September 3, 2005, identifies the Black Dispatch offices as being at 324 NE 2nd, which would place it a little west of the Slaughter building but on the south side of the street. And, CGHill of Dustbury also notes that Dunjee had originally set up shop at 228 E. 1st Street. There’s also this from Deep Second Still Lives In Dreams,

In the red brick buildings that lined NE 2 between Stiles and Central, there were two barbershops and a tailor shop – Ellison and Stewart both had earned extra money shining shoes at all three – a hardware store, a music store, a funeral home and the Black Dispatch newspaper office.

About the Black Dispatch, Bob Blackburn’s article gives this description:

In 1915 a loud voice was raised in this battle when Roscoe Dunjee founded the first black newspaper in Oklahoma City, the “Black Dispatch.” From his offices in Bricktown at 228 E. First, Dunjee and his allies organized the first local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, challenged legal barriers in the courts, and attacked the “Bloody Fangs of Jim Crow” in the halls of power. The efforts bore fruit, first with cracks in the wall, then with a growing volume of victories however small. Year after year, under constant attack, the walls of segregation would crumble, a fight started in the neighborhoods of Bricktown.

According to this source,

Roscoe Dunjee started the Black Dispatch in Oklahoma City in 1914. The son of a black West Virginian newspaper publisher, Dunjee worked in a print shop and wrote for several of Oklahoma’s black newspapers before starting his own journalistic venture.

Before the Black Dispatch, only six African-American newspapers had used black in their titles, and none of them lasted very long. Dunjee chose the title because whites used the phrase “black dispatch” as a slang term for gossip or untruths, and he felt that phrases like this insulted the integrity of the African American. So, by using it as the title of a newspaper and adhering to high standards of journalism, Dunjee wanted to attack racist attitudes and instill pride in black heritage.

Famous for his fiery editorials, Dunjee used the Black Dispatch to train black journalists, to attack discrimination, and to encourage the black community to fight for civil rights. Angered by the meek acceptance of Jim Crow many African Americans displayed, Dunjee wrote editorials criticizing blacks who didn’t vote or participate in politics. In an especially harsh 1920 editorial titled “Senseless Blacks,” he wrote: “The most disgusting and senseless Negro that we know is the fellow who stands around and says, ‘Oh I never vote; I’m not registered’ and who always slurs and tells you that the Negro who is active in politics in the community is selling you out and should not be trusted.”

When the Oklahoma Federation for Constitutional Rights began investigating discrimination in the State in 1941, Governor Leon Phillips called the organization “the height of folly” and claimed, “no one is denied constitutional rights in Oklahoma.” Dunjee responded with one of his lengthy trademark editorials, citing court cases and the activities of the NAACP:

On every train and bus in Oklahoma, this writer and all Negroes in Oklahoma are denied civil rights. Can the Governor observe denial of Negroes to Pullman and chaircar accommodations on railroads, and then like Pontius Pilate, wash his hands, saying ‘No one is denied constitutional rights in Oklahoma?’

* * *

When racial tensions exploded in Tulsa in the summer of 1921, resulting in an estimated 300 deaths and the destruction of the black community known as Greenwood, the Black Dispatch provided complete coverage, tried to silence rumors, and raised money for thousands of homeless black Tulsa residents. Dunjee, suspicious of the minor incident that sparked the violence, investigated the riot’s causes and editorialized that white business interests had hired agitators to rouse the white populace because they wanted Greenwood’s valuable real estate. The city’s new districting ordinances proposed such strict guidelines on the Greenwood district that black homeowners found the costs prohibitive. A Black Dispatch front-page story stated, “this latest fire limit ordinance shows plainly that Tulsa coveted also the very land upon which black men dwelt.”The Federal government investigated the Black Dispatch for disloyalty during World War II (WW II), and the FBI reported that the paper used known Communist phrases like “civil liberties,” “inalienable rights,” and “freedom of the speech and of the press.” The Black Dispatch survived this wartime scrutiny, but financial problems forced Dunjee to sell the paper to his nephew John Dunjee in 1955. It remained a family-run newspaper until it folded in 1982.

Roscoe Dunjee was inducted into the Oklahoma Journalism Hall of Fame in 1971, that organization’s inaugural year.

Avery Chapel AME Church. On edit, I’ve located images of another very attractive church which served the area at the Oklahoma City Metropolitan Library System. It was located at 429 E. 1st (NW corner of NE 1st & Geary) and was built in 1907, but I don’t know anything more.

Douglass School. Although none of the manifestations of “Frederick Douglass School” were, strictly speaking, located within the boundaries of “Deep Deuce”, they were nearby and without doubt were influential (particularly teachers there like Zelia Breaux, to be discussed in Part 3) not only to the “famous” which would emerge from Deep Deuce, but also to those who did not obtain that status. Hence, it is important to speak about the school.

In my initial post, I said that, “From what I’ve been able to glean, the 1st Douglass School was established in 1912 and was located at 112 S. Central (in what is now the Bricktown Ballpark). In 1915, the school was relocated to 200 E. California, but roughly in the same area. I’ve found no really good pics of either locale, but here’s that which I have.”

Dustbury’s CG Hill again comes to the rescue! He points out that Bob Blackburn says it differently, and, indeed, he does. In Bob Blackburn’s article, we read,

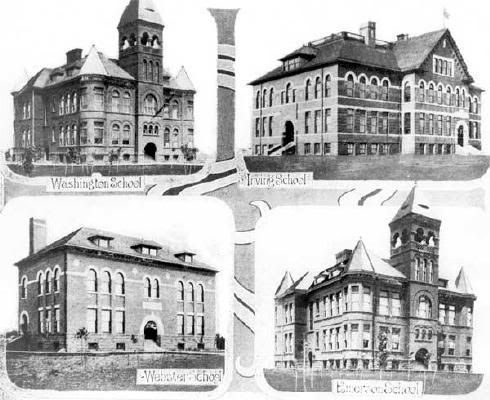

* * * Founded in 1891, the all-black school moved to a two-story frame building in the 400 block of East California in 1899, followed by a move into the old Webster School in 1903. From this new home at the northwest corner of California and Walnut (where the baseball park is located today), Douglass High School became one of the leading educational institutions in the region.

* * * Douglass High remained in the Bricktown Building until 1934 when it moved farther east and north.

The following 2 pics are from Vanished Spendor III, by Edwards, Oliphant and Ottaway (Abalache Book Shop Publishing 1985).

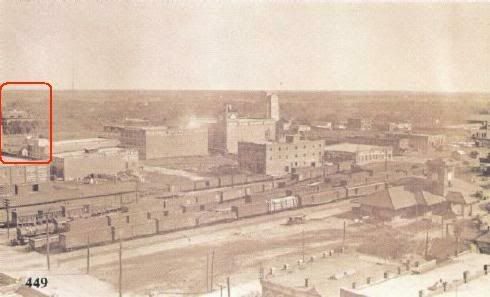

The authors identify Card 449 as being taken in 1915 from the top of the Herskowitz Building, looking southeasterly over what we now call “Bricktown”, and they identify the building at the “far left” as being Douglass School. From such a distance, no real clarity is present, but it does help to identify the location of the school at that time.

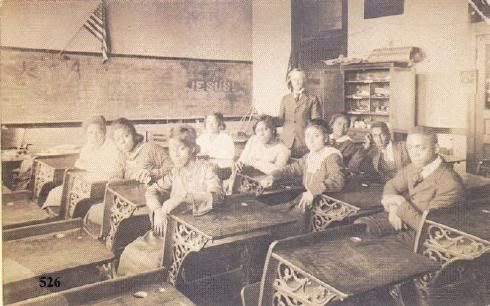

A 1915 pic of the faculty during that time – click for larger view

Yes, that’s “Jesus” written on the blackboard! How times change!

On edit, I found a couple of pics at the Metro Library System … in the 1st, in the lower left corner, is “Webster School”, which became Douglass around 1915. The address of this building is 200 W. California. After Douglass School moved to NE 6th & High in 1934 or 35, the former school became Wheatley School, shown in the 2nd picture. The notes about each pic are from the Metro Library System website.

Credit Oklahoma City Metropolitan Library System

Click on pic for a larger view

Wheatley School (formerly Douglass School), 200 E California

Looking Northwest (Jul 19, 1957) by John B. Fink

About Douglass School, Jimmy Stewart said in the 1993 interview:

“I’ll show you how we had to go to high school,” Stewart says. “See, the Rock Island tracks are right down south of here. You couldn’t get across there,”

He tells me to turn around and drive west on NE 1 to Central, then south over a viaduct that crosses the now abandoned tracks.

We reach Reno and turn back east.

“Now this corner right here’s the old Douglass High School,” Stewart says, pointing to what is now a city bus maintenance barn. The three-story school campus once covered the entire block, and to the east sat n the football practice field, he says.

“This was the third school for blacks in Oklahoma. They had one on Walker and Reno, then they had one over here on East Grand, and this was the pride of Oklahoma s City—Douglass High School.”

From what I’ve read, Douglass School moved in 1932 or 1935 (sources vary) to a school formerly known as “Lowell School” built in 1909 at 600 N. High, about 5 blocks east of what is now Lincoln Boulevard, and that building, though presently unoccupied, still stands.

This pic was taken by me Saturday afternoon, November 25 – click for larger view

After Douglass School relocated to a new facility on then Eastern now Martin Luther King, the school became the Page-Woodson School, now vacant. This source indicated plans were in the works to make the building an African-American cultural center and museum, but a September 2006 Journal Record article indicates that the property may be converted to office space.

Certainly, there is much more to say and this should only be considered as an introduction to those who are research-minded. But, the “Deep Second” that people like Ralph Waldo Ellison knew as a child is certainly now only a memory. Before his death (1994), Ellison is quoted in the following article, found at Deep Second Still Lives In Dreams:

As the black community moved farther north and east, [Jimmy] Stewart tells me, the center moved from NE 2 to NE 8 and eventually to NE 23. After the war, street cars were replaced by buses, and the busiest didn’t stop in the Second Street, he says.

“It just kept running down,” he says as we zip above the decaying buildings of Second Street on the raised highway. “More desirable places were opened up and it made Slaughter’s Hall inappropriate.”

Stewart says he doesn’t even remember when the dance hall closed. But its demise is one reason'” Ellison has not returned to the city of his birth.

“I hesitate to go back to Oklahoma City, especially now when I’m’ trying to finish a book,” Ellison had said. “To go back and find that old East Second Street environment gone is traumatic, it’s sort of disturbing and I don’t want to lose the memories. I don’t want to lose my sense of how it was, because after all, that’s where I came from.”

He was/is not the only one. When one is wanting to “go back” to see one’s homeplace and engage in a physical/emotional bonding with one’s past, but the physical past is no longer there, why do it?

Next: Part 3 about Deep Deuce People, about Ellison and others.