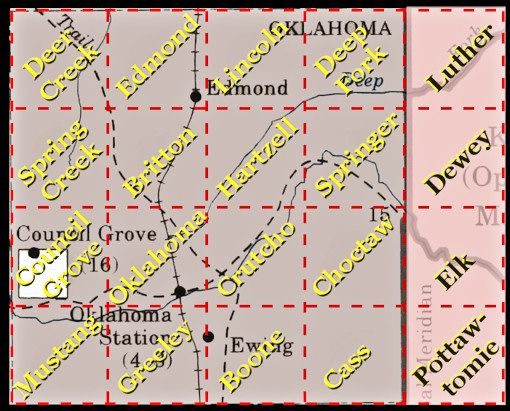

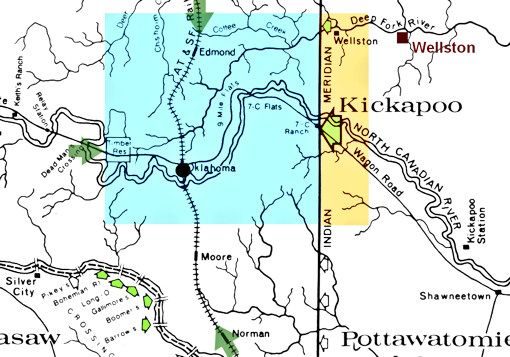

Oklahoma County forms a rectangle 30 miles wide by 24 miles high, almost exactly 720 square miles, as shown in the above map which contains annotations noting the county’s 20 original townships, each being 6 miles square. Almost all know that the county was initially populated by the Land Run of April 22, 1889, but not as many are familiar with the fact that our eastern 144 square miles were not included in that 1889 Land Run at all. This article’s purpose is to present, by maps and additional information, how Oklahoma County came to be the county that we know today and a little about its changes from the 1889 Land Run through the end of the nineteenth century, focusing on the towns that did not last to or much beyond 1900 — the latter portion is covered in Part 2 of this article.

This Part 1 covers the period from 1830 through “noonish” on April 22, 1889; Part 2 covers more particularly what is now Oklahoma County from “noonish” through 1900. I’m not saying “noon” since a bit of time overlap exists where these two periods blend and merge and, indeed, “noonish” is something more accurately akin to the “Twilight Zone” which, on that day, the entire area known as “Oklahoma country” surely was.

This story could start with the 1803 Louisiana Purchase by the United States which included the land we now call Oklahoma — or, of course, it could begin earlier than that for pre-USA days. Instead, I’ll start this story with 1830, the year that Congress adopted the Indian Removal Act which forced removal of the respective “Five Civilized Tribes” to what would later become the state of Oklahoma into Indian Territory — even though it wasn’t at that time formally called “Indian Territory.”

This story could start with the 1803 Louisiana Purchase by the United States which included the land we now call Oklahoma — or, of course, it could begin earlier than that for pre-USA days. Instead, I’ll start this story with 1830, the year that Congress adopted the Indian Removal Act which forced removal of the respective “Five Civilized Tribes” to what would later become the state of Oklahoma into Indian Territory — even though it wasn’t at that time formally called “Indian Territory.”

>>Click here for a 40 page PDF version of this file<<

Be Cautious About Maps 1830-1866 1866-1886 Civil War

The Boomers 1887-1889 Political History

Location & Size Note About Ewing

1st Land Run Law Legal Descriptions Boomers, Again

Sooners Legal Sooners How Many? Bibliography & References

A BEGINNING WORD OF CAUTION ABOUT VINTAGE MAPS. One of the funnest things to do when sniffing around internet websites is to locate really cool maps (e.g., the Library of Congress vintage maps collection or the University of Alabama’s similar collection) — at least, I find a good bit of pleasure in the hunt and then publishing them in Doug Dawgz Blog. I make this note for those similarly inclined or for others who don’t care for the hunt but just like to see really old maps from time to time.

THE IMPORTANT NOTE IS THIS: Don’t assume that the cartographers got it right and that what is presented contains altogether reliable information. Not too infrequently, they don’t. A simple and fairly benign example is that almost if not all pre-1900 Rand McNally maps locate Wellston in Oklahoma County (or in the area that would become Oklahoma County), a mistake shared by other mapmakers. In fact, Wellston is located about 4 miles east of the Oklahoma County line (and about 10 miles east of the Indian Meridian).

Other maps contain much more misleading and serious errors. I located three such maps when doing research for this particular article. The first two that I’ll mention are shown below:

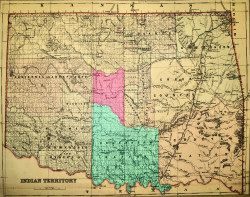

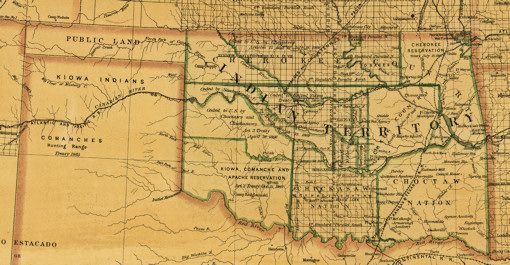

From the Library of Congress: A Crop From Colton’s Map of Texas & Indian Territory (1872) |

A Map Located at the Oklahoma State Library Photographed on October 25, 2010 |

Yes … both maps look good and contain detailed information in them that gives all appearances of accuracy. So, what’s the problem?

Before editing this article on October 30, 2010, the initial October 28 post relied on this map to show Indian Territory as of 1872 and to narrow down the Unassigned Lands and Oklahoma County’s location within it. Then, when focusing on detail of the parts of Indian Territory that became parts of the Unassigned Lands, from where and when, I looked more closely at this map than I initially did. Look at the green center-left irregular shaped area at the top part of this map. In large letters, it reads, “Cheyennes and Arapahoes.” Click on the map if you can’t see that.

Being little better than a novice in my knowledge of Oklahoma during this time period, I tried to determine when it was that the “green area,”, mostly part of the Cherokee Nation (as well extending further south of the Cherokee area than it ever did), became an asset of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. I searched in vain. The truth is that it never happened. The cartographer who prepared the map made a huge, and, for a cartographer, unforgivable, mistake. Except for tracts which were ceded by the Cherokees to the United States for the formation of other Indian tribal areas (Osage, Kaw, Tonkawa, Ponca, Oto & Missouri, and Pawnee), the vast majority of the area called the Cherokee Outlet remained the property of the Cherokees until it deeded the Outlet to the United States in 1891. See Josh Clough’s essays in Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 2006) at pages 120-121 and 130-131. The Cherokee Outlet area was never a reservation for the Cheyenne and/or Arapaho tribes.

Given such a huge error, caution naturally arises even if other parts of the map are accurate (as many if not most probably were). Such a major gaffe in a map gives rise to caution about everything else that it contains. This wasn’t the last early map to contain a similar error — see the discussion about the 1887 map of Indian Territory prepared by the Department of the Interior, General Land Office, discussed in the Unassigned Lands area later in this paper.

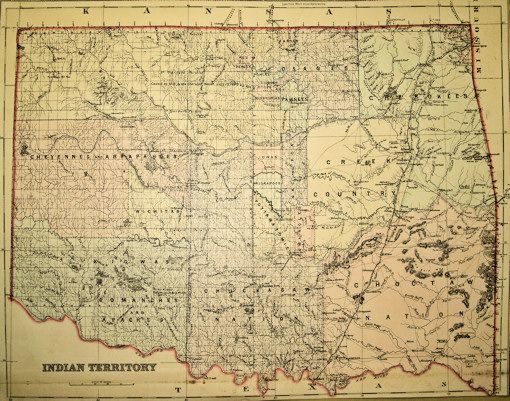

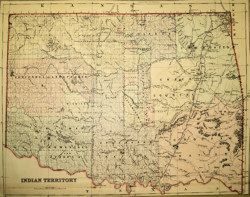

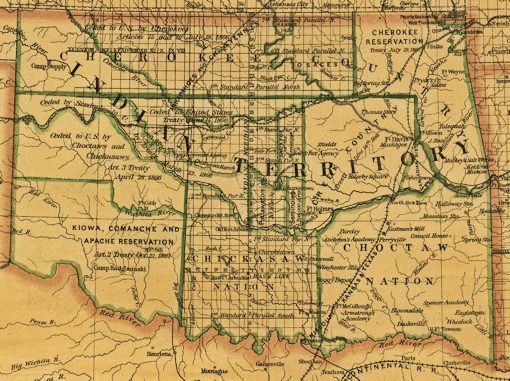

When I first saw this map on October 25, I thought, “Wow! What a cool find and it is nowhere available on the internet. I’ll be the 1st to publish it.” (Maps located at the Oklahoma State Library’s archives at 200 N.E. 18th are not digitalized or on-line and one must look through a 3-ring binder paper index book which doesn’t contain images to identify what a researcher would ask to see and which are not chronologically organized. Once identified by a researcher, original maps are then courteously delivered and then one may take a photograph of the map with one’s camera.)

Well, I am (to my knowledge) the first to publish this map on the internet. Although this map is not dated nor is the cartographer identified and is simply labeled, “Indian Territory,” the time-stamp of the map can be fairly well determined to be between 1881 and 1886. Several items shown in the map did not exist in early-day Indian Territory: In 1870, construction began in the north on the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (commonly called KATY) railroad running through eastern Indian Territory and it was done when the line reached Texas in 1872; in north-central-east Indian Territory, areas were set aside for several tribes from areas in the Cherokee Outlet (Osage 1872; Pawnees 1876; Poncas 1881; Otos and Missouris 1881). The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad is not shown in the map and its construction was completed in 1887. Hence, the map was made between 1881 and 1886 and is in many ways a very cool map.

So, what’s the problem? Have another look at the above map and look closely at the Chickasaw Nation — it extends north to the Cimarron River, well beyond its northern boundary of the (South) Canadian River which is shown in every other map I’ve seen of the Chickasaw Nation, regardless of date. My wife, Mary Jo Watson, is a Native American art expert and is Director of the School of Art at the University of Oklahoma, and so might have some knowledge about this. I asked her, “Did the Chickasaw Nation ever extend that far north,” and she said, “Not that I know of.” Wanting more certainty than that, I asked her if she had in her enormous Native American library of books something that would show the exact detail I was looking for. She pulled four general Oklahoma/Indian Territory books but none gave the detail that I wanted. Then, I looked more closely at a book in my own library, the excellent Historical Atlas of Oklahoma by Charles Robert Goins and Danney Goble (University of Oklahoma Press 2006). Therein, it became clear that the Chickasaw Nation never extended north of the (South) Canadian River. Consequently, other than in this section, I make no other reference to this particular map, as nifty as it is.

So, what’s the problem? Have another look at the above map and look closely at the Chickasaw Nation — it extends north to the Cimarron River, well beyond its northern boundary of the (South) Canadian River which is shown in every other map I’ve seen of the Chickasaw Nation, regardless of date. My wife, Mary Jo Watson, is a Native American art expert and is Director of the School of Art at the University of Oklahoma, and so might have some knowledge about this. I asked her, “Did the Chickasaw Nation ever extend that far north,” and she said, “Not that I know of.” Wanting more certainty than that, I asked her if she had in her enormous Native American library of books something that would show the exact detail I was looking for. She pulled four general Oklahoma/Indian Territory books but none gave the detail that I wanted. Then, I looked more closely at a book in my own library, the excellent Historical Atlas of Oklahoma by Charles Robert Goins and Danney Goble (University of Oklahoma Press 2006). Therein, it became clear that the Chickasaw Nation never extended north of the (South) Canadian River. Consequently, other than in this section, I make no other reference to this particular map, as nifty as it is.

The above should be more than enough information to cause a researcher or a casual reader to take care: Just because something is shown in a vintage map doesn’t make it so. This doesn’t mean that the vintage maps don’t contain useful information — it just means that such maps should be looked at with eyes wide open and should be investigated for accuracy using other sources than the maps themselves.

1830-1866: INDIAN TERRITORY. The Five Civilized Tribes that were forced to relocate here from the southeastern United States were the Choctaws (beginning in 1825-1831, largely from Mississippi but also from Alabama and Louisiana), Creeks (beginning in 1832, from Alabama, Georgia, and Florida), Seminoles (beginning in 1832, from Florida), Chickasaws (beginning in 1837-38, largely from Tennessee and Mississippi but also from Missouri and Alabama), and the Cherokees (beginning in 1835, from parts of Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia, and Virginia, as well as from earlier removal areas in Arkansas and Texas). The following crop from a graphic contained in Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 2006) shows the original homelands of these tribes before removal.

Although the focus of this paper is the formation of Oklahoma County, and while neither the Oklahoma County nor the Unassigned Lands only include lands from ALL of the Five Civilized Tribes, for completeness in this section I’ll broadly trace each of the Five Tribes’ areas between 1830 and 1866, below. Understand from the outset of this discussion that the area which eventually became the “Unassigned Lands” and the piece of it which would become Oklahoma County were only from parts of Indian Territory which were, at one time or another, parts of the Creek and/or Seminole Nations.

A Note About The Information Contained In This Section. Most of the information I’m reporting in this section derives from essays contained in Historical Atlas of Oklahoma by Charles Robert Goins and Danney Goble (University of Oklahoma Press 2006). The book is actually a collection of numerous 2-4 page essays written by different authors and if the excellent book has a shortcoming it is that the independently prepared essays are nowhere completely pulled together to present a cohesive summary (or summaries) of what the individual writers had to say. Additionally, the book must be understood to be what it is — an atlas. The spatial requirements inherent in an “atlas” force material to be presented in a condensed summary form. This is not a criticism — this book presents vastly more information than many atlases do — it is simply a recognition that when compressing information about particular topics (e.g., about a particular tribe or other topic) into a 2-4 page area, that process can and probably did force over-generalizations to be made. Each 2-4 page topic would easily be the proper content of one or more individual volumes, if treated thoroughly. But that is not the function of an atlas.

My intent in this section is much like that in the 2006 Atlas, to paint a reasonably accurate broad-stoke picture, without a great deal of detail thrown in. See this PBS article and this one from the Oklahoma Historical Society or buy many books for more complete descriptions.

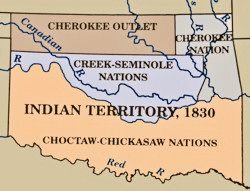

The drawing at right from the Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (2006) purports to show Indian Territory circa 1830, inclusive of the portions of Seminole and Creek Nations which would shortly become parts of what would come to be called the “Unassigned Lands.” This drawing is NOT representative of Indian Territory as of 1830 but is more accurately what Indian Territory looked like circa 1837-38. It presents in graphic form the areas which the Five Tribes came to occupy before the original Choctaw area was divided between the Choctaws and Chickasaws in 1855 and the original Creek area was divided between the Creeks and Seminoles in 1856.

The drawing at right from the Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (2006) purports to show Indian Territory circa 1830, inclusive of the portions of Seminole and Creek Nations which would shortly become parts of what would come to be called the “Unassigned Lands.” This drawing is NOT representative of Indian Territory as of 1830 but is more accurately what Indian Territory looked like circa 1837-38. It presents in graphic form the areas which the Five Tribes came to occupy before the original Choctaw area was divided between the Choctaws and Chickasaws in 1855 and the original Creek area was divided between the Creeks and Seminoles in 1856.

The following drawings from the Atlas (which I’ve sometimes modified for clarity) trace each tribe’s initial area within the territory.

The Choctaws were the first of the Five Tribes to relocate to Indian Territory during 1825-1831, followed in 1832 by the Creeks. Each of these tribe’s areas would shortly be co-occupied by another of the Five Tribes.

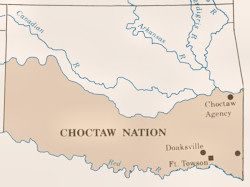

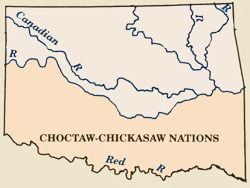

Initial Choctaw Area 1825-1831 |

Initial Creek Area 1832 |

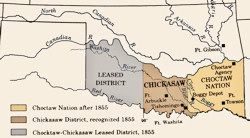

The next of the Five Civilized Tribes to move to Indian Territory were the Chickasaws. Initially, the Choctaws sold Chickasaws the right to settle in the western part of their nation and removal occurred in 1837-1838. Although the preferred area of their settlement was in the west, the Chickasaws could also settle anywhere in the Choctaw Nation. During this time, the Chickasaws were subject to Choctaw law and the tribe had no “nation” to itself. That changed in 1855 when a new treaty set up distinct areas for the Chickasaws and Choctaws and also included a provision that the westernmost part of the area become a “Joint Use” area which was leased to the United States.

Joint Choctaw-Chickasaw Area 1837-1838 |

Choctaw & Chickasaw Areas 1855 |

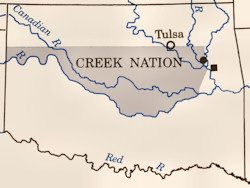

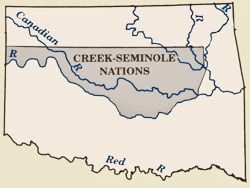

Similarly, the initial area set aside for the Creek Nation was co-occupied by the Seminole Nation, its removal to Indian Territory beginning in 1832-33 but continuing through 1859. The area was divided in 1856 to provide for distinct areas for each tribe. Parts of the areas of these tribes would later become the “Unassigned Lands.”

Creek & Seminole Tribes 1833 |

Seminoles & Creeks 1856 |

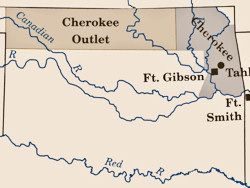

The last Five Civilized Tribe area to be carved out in Indian Territory was in 1835 for the Cherokees and it consisted of two parts — the primary area for the nation in the northeast and the long horizontal area on the north which was called the Cherokee Outlet.

The last Five Civilized Tribe area to be carved out in Indian Territory was in 1835 for the Cherokees and it consisted of two parts — the primary area for the nation in the northeast and the long horizontal area on the north which was called the Cherokee Outlet.

The map shown at left is from the Library of Congress website and was prepared by various cartographers principally between 1854-55 per an order issued by Jefferson Davis (shown below, right), then Secretary of War under President Franklin Pierce but, of course, later to become the President of the Confederate States of America, 1861-1865, to accompany the reports of explorations for the establishment of one or more railroad routes from the Mississippi River to California. The map does not reflect the 1856 division of the area occupied the Creeks and Seminoles nor does it reflect the 1855 division of the Choctaw and Chickasaw area into distinct components. Notes present in the map reflect dates ranging from 1847 to 1853. For a reason that I don’t know, the Chickasaws are not mentioned but, in the southwest part of the territory, the Wichitas are.

The map shown at left is from the Library of Congress website and was prepared by various cartographers principally between 1854-55 per an order issued by Jefferson Davis (shown below, right), then Secretary of War under President Franklin Pierce but, of course, later to become the President of the Confederate States of America, 1861-1865, to accompany the reports of explorations for the establishment of one or more railroad routes from the Mississippi River to California. The map does not reflect the 1856 division of the area occupied the Creeks and Seminoles nor does it reflect the 1855 division of the Choctaw and Chickasaw area into distinct components. Notes present in the map reflect dates ranging from 1847 to 1853. For a reason that I don’t know, the Chickasaws are not mentioned but, in the southwest part of the territory, the Wichitas are.

This is the earliest cartographer’s map that I’ve located so far which shows the location of the five tribes plus, in the far northeast corner of Indian Territory, the small areas set aside for the Quapahs, Senicas, and Shawnees. The LOC downloaded map is very large, 14,175 x 14,112 pixels, but you can click on the above-left image for a 2,500 pixel wide view.

This is the earliest cartographer’s map that I’ve located so far which shows the location of the five tribes plus, in the far northeast corner of Indian Territory, the small areas set aside for the Quapahs, Senicas, and Shawnees. The LOC downloaded map is very large, 14,175 x 14,112 pixels, but you can click on the above-left image for a 2,500 pixel wide view.

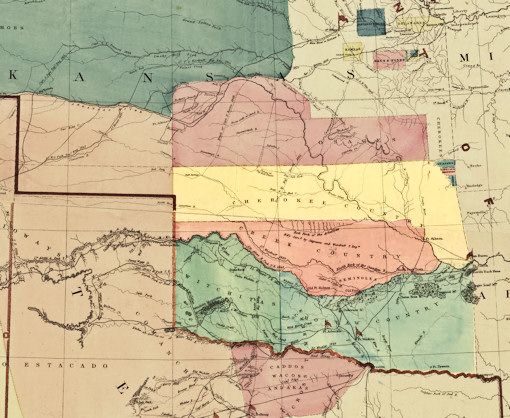

A crop from that map shows parts of Kansas and Texas and all of Indian Territory nicely. Click on the cropped image below for a 3,391 pixel wide view of the same map.

Although the words “Indian Territory” do not appear in the above map, the yellow northern border of the Cherokee Nation appears to be the northern border of Indian Territory and the southern border of Kansas. As or more importantly, note that in Kansas substantial portions were Native American areas at the time. Immediately north of the Cherokee area is the large plum-colored area of the Osage. Above the Osage area (though not shown in the above crop) is a large area for the Cheyenne (spelled Sheyenne in the map) & Arapaho. Fairly close to Kansas City are smaller Pottawatomie, Delaware, Sac & Fox, and Ottawa areas. In Texas, in the west area including the Texas panhandle were the Comanches, and south of the Red River were the Comanches, Caddo, Waco, and Andakas. Many other tribes that would be forced to relocate to Indian Territory by coerced agreements are not shown in the above crop. Kansas wanted its area to be exclusively for white settlement, and so did Texas.

It comes as no surprise, then, within 20 years, Indian Territory would be substantially reconfigured notwithstanding promises which accompanied their removal from southeastern parts of the United States which carved out areas for each of the Five Civilized Tribes to several others but some not reassigned to any tribe at all. Of course, these changes occurred by agreements of the tribes, agreements made with a not-so-figurative gun to their heads, particularly after the Civil War.

1866-1886: DEVELOPMENT OF THE UNASSIGNED LANDS. I could begin and end this section by one simple paragraph which might read,

The Unassigned Lands derive from territory which was, at one time, all part of the Creek Nation, but which was later divided between the Creeks and Seminoles, but which was lost to both tribes after the Civil War, and the Unassigned Lands (including the largest part of Oklahoma County) were from parts of that lost territory.

But, where’s the fun in that? Additionally, the brief description doesn’t set the stage for the expansion of the Oklahoma County area after the 1889 Land Run eastward to include an additional six lineal miles which wasn’t part of the Unassigned Lands and increased Oklahoma County’s Indian lineage to include the Iowas, Pottawatomie and Shawnees, and the Kickapoos.

The short version just won’t do. This section contains a longer version of the story.

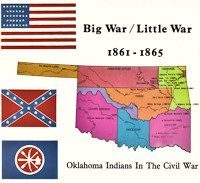

The Civil War. The U.S. Civil War (1861-1865) provided the excuse if not necessarily the reason for the identification of what would become the Unassigned Lands within Indian Territory. All Five Civilized Tribes formally associated with the Confederacy — notwithstanding that individuals and groups within the tribes aligned themselves with the North — the United States.

For an excellent reference about and review of the Five Tribes’ involvement with the Civil War, including battles fought in Indian Territory and the tension within the tribes on the matter, read Tim Wantland’s 16-page essay, Big War/Little War – 1861-1865 – Oklahoma Indians In The Civil War (Center of the American Indian 1985), never published on the internet until now. I’m honored and pleased to say that the booklet’s author is a stepson of mine, but, more important to this discussion, he is steeped in and possesses expertise about early Indian/Oklahoma Territory history.

For an excellent reference about and review of the Five Tribes’ involvement with the Civil War, including battles fought in Indian Territory and the tension within the tribes on the matter, read Tim Wantland’s 16-page essay, Big War/Little War – 1861-1865 – Oklahoma Indians In The Civil War (Center of the American Indian 1985), never published on the internet until now. I’m honored and pleased to say that the booklet’s author is a stepson of mine, but, more important to this discussion, he is steeped in and possesses expertise about early Indian/Oklahoma Territory history.

When discussing this article with him, he noted that the Civil War caused only one state — Virginia — to lose territory, and that by choice when western Virginians voted not to secede from the Union and formed itself as a new State, West Virginia, admitted to the Union in 1863.

But, to some extent, the lingering question is not completely answered: Why did the Five Tribes align themselves with the Confederate States of America despite their excruciatingly harsh treatment by Tennessean U.S. President Andrew Jackson as well as by others within the states of their previously occupied areas? Although probably an oversimplification, probably the tribes put their past hurts behind them and saw that they wanted the same thing that the states of the Confederacy did — independence.

As an example, on May 25, 1861, the Chickasaw Nation adopted its own “Declaration of Independence.” Excerpts from that declaration are contained in one of the several masterpiece books written by the renowned University of Oklahoma historian Arrell Morgan Gibson, this one being The American Indian, Prehistory to the Present (D.C. Heath and Company 1980), at page 364:

Whereas the Government of the United States has been broken up by the secession of a large number of States composing the Federal Union … and Whereas the Lincoln Government, pretending to represent said Union, has shown by its course toward us, in withdrawing from our country the protection of federal troops, and … a total disregard of treaty obligations toward us … Therefore, Be it resolved by the Chickasaw Legislature assembled … That the dissolution of the Federal Union … has absolved the Chickasaws from allegiance to any foreign government whatever; that the current of the events of the last few months has left the Chickasaw Nation independent, the people thereof free to form such alliances, and take such steps to secure their own safety, happiness, and future welfare as may to them seem best … Resolved, that the Governor of the Chickasaw Nation be, and he is hereby instructed to issue his proclamation to the Chickasaw Nation, declaring their independence.

At page 365, Dr. Gibson notes,

Southern leaders had two broad goals: (1) to separate from the United States in order to pursue an independent national life, free of pressures and threats of the abolitionist crusade and the laws of Congress, and (2) to absorb that part of the West recently denied it as an area for expanding its institutions, particularly slavery.

The Five Tribes all originating from the southeastern United States were all slave-owning tribes, as well, so the above description fits those tribes precisely. More ominously to the Five Tribes, Dr. Gibson also reports at page 366,

Likewise, trial leaders were disturbed by the election in 1860 of Abraham Lincoln as President. His campaign workers, notably William H. Seward, in order to appeal to Free Soil voters, had recommended appropriating the land of the Five Civilized Tribes and opening it to white settlers.

Consequently, it should come as no surprise that the Five Tribes were more comfortable and compatible with the Confederacy than they were with the Union.

The dice didn’t land right — it was snake-eyes instead of the hoped/expected for 4+3 = 7. The southern states, and the Five Tribes, would have to pay, and following the war the Reconstruction Act of 1866 caused the lands of the Five Civilized Tribes to be forever changed. In an essay by Michael D. Green in Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 2006), p. 98, he said,

On June 23, 1865, General Stand Watie surrendered all Confederate military forces in Indian Territory. Shortly thereafter a Federal peace commission convened a grand council of tribal representatives at Fort Smith, but the final negotiations and treaty signings took place in Washington in 1866. The Federal position was that the Confederate treaties had erased more than a century of treaty relations and obligations between the United States and the tribes. There had to be a new beginning.

While the effects were staggering, the terms were few and simple. The nations rescinded their Confederate treaties and made peace with the United States, they emancipated their slaves and agreed to extend to the freedpersons [black slaves within the tribes] full and equal rights of citizenship, and they agreed to grant rights-of-way to railroads, accept the jurisdiction of federal district courts in cases involving non-Indians, work toward the establishment of a uniform government for Indian Territory, and sell to the United States large blocks of land to be distributed to the tribes previously removed to Kansas and to the tribes of the southern plains. The United States agreed to reinstate relations with the nations. The details differed from treaty to treaty, but the pattern applied to all.

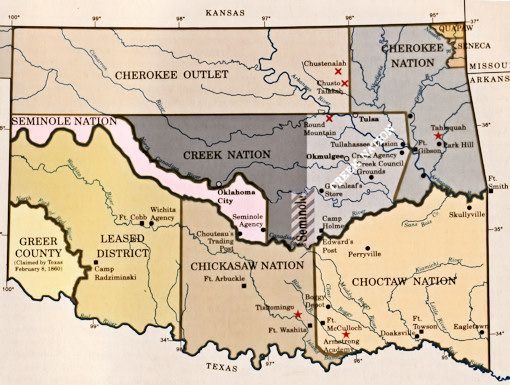

In their combined treaty, the Choctaws and Chickasaws ceded their jointly owned Leased District. By 1870 the United States had designated portions of it as the Cheyenne and Arapaho Reservation; the Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache Reservation; and the Wichita and Caddo Reservation. The Seminoles ceded their entire nation, part of which was included in the Cheyenne and Arapaho Reservation, while another part became the Pottawatomie and Shawnee Reservation. The Seminoles then purchased a new nation carved out of the Creek cession. The Creeks gave up the western half of their nation, into which the government moved the Iowas, Sacs and Foxes, and Kickapoos, as well as the Seminoles. The Cherokees agreed to sell the Neutral Lands and the Cherokee Strip, both of which were in Kansas, and and accepted the government’s plan to move the Osages, Tonkawas, Poncas, Otos and Missouris, Kaws (Kansas), and the Pawnees into the eastern half of the Cherokee Outlet. The government retained as “Unassigned Lands” a large block in the Creek cession that was never designated as reservation land.

The last portion of that statement is incorrect, as relates to the Unassigned Lands not being designated as a reservation, since the area was, immediately before 1866, part of the territories of the respective Seminole and Creek Nations. If any part of earlier treaties prevented either tribe from residing on part of their respective territories I’m presently unaware of such a fact but, in any event, the areas were clearly parts of the territories of each of those tribes. They were not “unassigned” — they were “unreassigned” lands.

Let’s have a closer look. We’ve already seen that the Unassigned Lands area was included in the territory assigned to the Creek Nation in 1832, that the Seminoles also came to occupy the same area in 1833, and that the original area was divided between the Creeks and Seminoles in 1856.

The Seminole and Creek Nations were by far the biggest territory losers post-Civil War. The Seminole Nation ceded its horizontally sweeping and relatively narrow tract running generally east to west bounded by the North Canadian and [South] Canadian rivers in to the United States on March 21, 1866. In another essay by Green in Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (2006), he said,

The 1866 Reconstruction treaty required that the Seminoles cede to the United States their entire country, a tract of 2,170,000 acres, for fifteen cents per acre ($325,500). This was their punishment for having sided with the Confederacy. To replace this land, the United States agreed to sell the Seminole Nation, for fifty cents an acre, a 200,000-acre tract cut from the southeastern corner of the cession wrung from the Creeks in their Reconstruction treaty. But the Seminole agent moved the people onto the tract before it was surveyed and inadvertently put them east of the line, on Creek lands. After years of argument over jurisdiction and despite prolonged opposition from a substantial settlement of Creeks, in 1882 Congress purchased an additional 175,000 acres from the Creeks, at one dollar an acre, and deeded it to the Seminoles, thus nearly doubling the size of their nation. The Seminoles quickly established their capital at Wewoka.

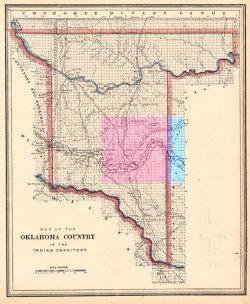

Shortly thereafter, on June 24, 1866, the Creeks ceded substantially all of its area south of the Cherokee Outlet down to the (South) Canadian River, more particularly shown in the next map. That pair of transfers made the Unassigned Lands available for definition. The drawing below from the 2006 Historical Atlas of Oklahoma showed Indian Territory in 1856 after the Seminole Nation’s area was specifically carved out of the Creek Nation’s, but I’ve modified the map to show the changes to both Nations after the 1866 transfers by those two tribes — changes to the other Nations’ territories are not shown.

The pink area identified is the Seminole Nation in 1856 and it was altogether gone in 1866. Instead, the Seminoles received the much smaller area located within the Creek Nation shown by the diagonally colored pink/gray area. The Creeks lost all of the area shown in dark gray in the west and the part just described for the Seminoles, it retaining only the light gray area immediately south and east of the Cherokee Nation.

But, the 1866 treaties with the Creeks and Seminoles contained provisions that the ceded areas be used only for settlement by other Indians or freedmen, and the cessions were conditioned upon those treaty requirements. As will be seen, this, too, would pass.

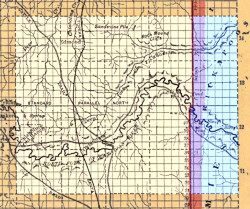

The 1873 map prepared by the U.S. General Land Office which is located at the Library of Congress website shows the effect of the Seminole and Creek transfers as to the area which would come to be know as the Unassigned Lands. Cropped versions of that map are shown below. As always, click on a map for much larger view. The image on the right shows the area which would become the Unassigned Lands and the part of Oklahoma County included within it.

|

|

This map derives from the huge (23,904 x 14,686 pixels) map located at the Library of Congress website Map of the United States and Territories prepared by the General Land Office in 1873. I’ve resized it to 8,000 pixels wide and you can download that version here. I’ve cropped the original to show two views of Oklahoma — one with a panhandle and one without, noting that the panhandle was never a part of Indian Territory. I’ve included the panhandle version since it clearly shows a railroad, the Atlantic & Pacific, running across the northern portion of the Unassigned Lands. See this Library of Congress website image for a closer look at the planned-for route. In Indian Territory, that railroad was never built west of Tulsa but it is interesting to see what was in place to be constructed — and which would have provided an additional point of entry for the 1889 Land Run. Also, see this Wikipedia article. The railroad makes no appearance in the Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (2006) nor in Cram’s 1889 Oklahoma Country map which will be described shortly.

Focusing in on the Indian Territory portion of this map more clearly shows the area and eastern boundary of the Unassigned Lands area, the Indian Meridian, even though, as such, the term “Unassigned Lands” it is still not referenced or delineated in the map.

During the remainder of this period, some areas of the lands ceded by the Five Tribes were assigned to other tribes, but some were not, but with the 1866 promises that they would be, and land surveying occurred, some of which is already visible in this 1873 map.

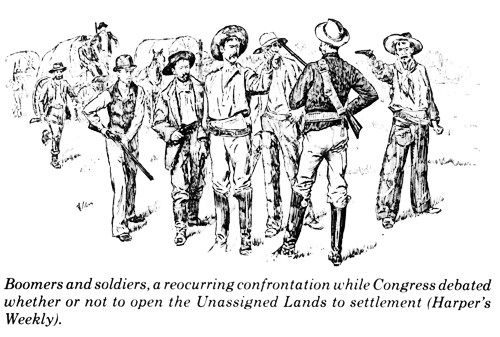

The Boomers. As will be discussed further in the next section (1887-1889, particularly Chapter 1 of Hoig’s The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 [Oklahoma Historical Society 1984]), agitation began to mount for all of Indian Territory to be opened for non-Indian settlement. Since the areas lost by the Seminoles and Creeks in 1866 were not then assigned to any tribe, and hence being most vulnerable, those areas received the focus of non-Indian settlement attention. Beginning around 1879-1880 and extending through 1886-1887, the “Boomer” movement became full-blown. Initially led by David Lewis Payne (for whom Payne County is named), numerous forays into the territories lost by the Seminoles and Creeks in 1866 occurred, the object of these incursions from Kansas being to establish settlements within the still-non-yet-called Unassigned Lands areas, including the area which would become Oklahoma County. All of those forays were illegal and all failed — not uncommonly the Boomers were forcibly escorted back to Kansas by the black U.S. Cavalry units stationed at Ft. Reno, the “Buffalo Soldiers.” See Cops & Robbers (1) – Boomers & Sooners and this OHS Digital Library article by Stan Hoig for more about the Boomers. After Payne died in November 1884, his lieutenant, William L. Couch (Oklahoma City’s first [provisional] mayor), assumed the role of the group’s leadership.

The Boomers and others also agitated politically to open some or all of Indian Territory, including the Unassigned Lands which was a part of it, to non-Indian settlement, that activity finally succeeding in early 1889, as will be shortly discussed.

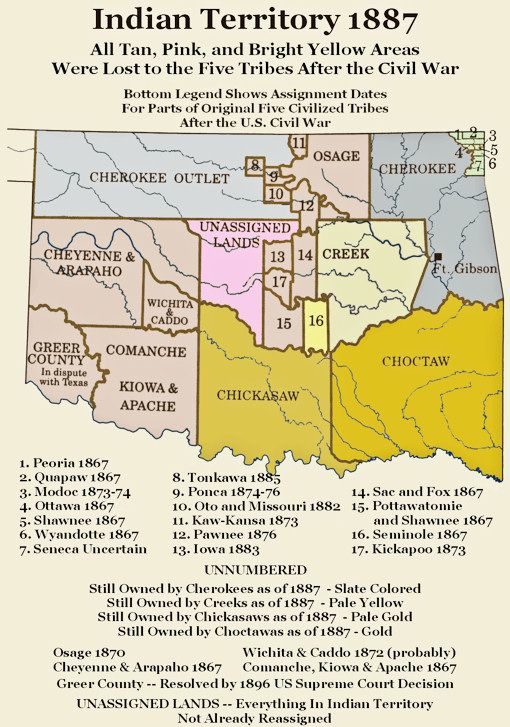

By the end of this period, Indian Territory was radically different than it was before the beginning of the Civil War. Below, I’ve used a drawing in the Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 2006) as a base map but I’ve modified it by color and content notes to reflect the changes which had occurred by 1887. Largely, the notes about tribal assignment are taken from two of Arrell Morgan Gibson’s books, The American Indian, Prehistory to the Present (D.C. Heath and Company 1980) and The Oklahoma Story (University of Oklahoma Press 1978). The map title and notes at the top and bottom are my doing and are not part of the map contained in the 2006 Atlas. If you don’t know who Arrell Morgan Gibson is/was, he is without doubt the preeminent Oklahoma historian ever … ever. So, if I found variances from other sources (including the 2006 Atlas, as I did), I’ve invariably opted for Gibson’s content in this paper above any other source.

By this time, all parts of Indian Territory had been reassigned, except for those parts in central Indian Territory which had not been — the now-called Unassigned Lands but but more correctly called the Unreassgned Lands.

1887-1889. By 1887, the crescendo leading to the April 22, 1889, Land Run was well under way.

The graders for the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe railroad arrived in what would become Oklahoma station in the fall of 1886 and it was then that the first permanent structure was built there — a post office and trading store built by trader William Decker. At that time and until July 1887, Oklahoma station wasn’t called that — it was called Seymour. See Hoig, p. 31. The section between Oklahoma station and Arkansas City, Kansas, opened mid-April 1887 with the rest of the track between Oklahoma station and Gainesville, Texas, being done later in the year.

The establishment of this north-south railroad, the first north-south railroad in the territory and piercing thorough the center of Unassigned Lands, probably sealed whatever doubt that may have existed that the area would be opened for non-Indian settlement, but there were still political bridges to cross.

To skip the “political history” section below and move to the discussion of the location of the Unassigned Lands, click here.

Political History. In my review of available sources, one source stands well above the rest in presenting a succinct and thorough review of developments during this period, and that source is Stan Warlick Hoig’s The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 (University of Oklahoma Press 1884).

Political History. In my review of available sources, one source stands well above the rest in presenting a succinct and thorough review of developments during this period, and that source is Stan Warlick Hoig’s The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 (University of Oklahoma Press 1884).

About Stan Hoig: Born June 24, 1924, at Duncan, Oklahoma, he died December 30, 2009, in Edmond. He earned his bachelor’s degree in English at Oklahoma A&M College and his master’s degree at the University of Oklahoma in 1964 where he received his Ph.D. in 1971. In 1985 he was named as Distinguished Scholar by the University of Central Oklahoma Chapter of University Professors. Hoig has 25 books listed with the Library of Congress, plus other works.

|

See this link for more about Dr. Hoig who is a primary source in any study of Oklahoma history.

This book contains numerous illustrations from Harper’s Weekly which closely covered events surrounding the 1889 Land Run, one of which is included in Chapter 1. It would have been such a privilege to have met and talked with Stan Hoig, but we at least have the benefit of him speaking with us through a part of his life’s work and love, his literature. Rather than me giving an amateurish summary of the events that led to the April 22, 1889, Land Run, Dr. Hoig does that ever so much better in Chapter 1 of his book, below. |

Relive, now, through Dr. Hoig’s words the time leading to the April 22, 1889, Land Run, between 1887 and the guns and canons which signaled the time of day on Monday noon, April 22, 1889. Click on an endnote number to read the note or to return to a point in the text.

LONG had the white man coveted this land, and now it would be his. When the Indians of the South had been removed to this then-remote part of Western America beyond the Mississippi River, President Andrew Jackson had promised that their new home would be theirs for “as long as the grass grows or the water runs, in peace and plenty.” [1] But following the Civil War, white men began looking to westward expansion, and numerous bills were submitted to Congress to make a state out of the Indian Territory. Leaders of the Civilized Nations of the Territory had effectively resisted these moves through the decades of the 1860s and 1870s. But it was one of their own, Colonel Elias C. Boudinot, a Cherokee lawyer and railroad lobbyist, who first publicized the significant fact that some two million acres of land had been left unassigned to any Indian tribe following treaties between the United States and the Creeks and Seminoles in 1866. It was this area located at the very heart of the Indian Territory which now came to be known popularly as the “Oklahoma country.” In the spring of 1879, Colonel C.C. Carpenter, a Kansan who affected the long curls and buckskin modes of Custer and Hickok, was encouraged by the Kansas City Times to promote the invasion of the Oklahoma country. Though Carpenter himself remained safely in Kansas, a small intrusion did take place in May 1879. Settlers from Kansas and Missouri reached the North Canadian River of the Oklahoma country before being removed by U.S. troops. Carpenter, when confronted by Indian Bureau officials and threatened with imprisonment, quickly went into hiding and forsook his invasion scheme. It was left to Captain David L. Payne, an early Kansas pioneer, politician, and soldier, to ignite a continuing “Oklahoma boomer” movement to invade and colonize the Oklahoma lands. From 1880 until his death in November 1884, the hard-drinking ne’er-do-well of the frontier led settlement intrusions from Kansas and Texas into the Oklahoma country despite strong federal opposition and continued removal by U.S. army units. Payne recruited followers, agitated in the press and at public meetings, fought his battle in the courts, and lobbied in the halls of the Congress with great persistency until the Oklahoma movement had become a national issue. Following Payne’s death, the Oklahoma cause was carried on under the leadership of William L. Couch, a former Payne lieutenant. Though Couch led his own invasions of Oklahoma, legal pressures and continued resistance by the U.S. government brought the Oklahoma movement to an impasse by 1886. But it was then a highly significant event took place with the construction of the Santa Fe Railroad line across the Indian Territory from Arkansas City, Kansas, to Gainesville, Texas. This line, which was completed in the spring of 1887, ran directly through the center of the Oklahoma country. The Boston Transcript astutely observed: “This will inevitably open up the long coveted Oklahoma land to settlement by whites.” [2] The Arkansas City Traveler was also quick to note that the new route offered dual advantages to the railroad and the Oklahoma boomer. Settlement of the Oklahoma land would open new market areas for the railroad. The boomers, by attaching themselves to the railroad grading and construction crews, could gain entry into Oklahoma. The military would have no power to stop them while they traveled “unmolested to the promised land.” [3] Thus during 1887 little was heard from the boomer movement. Construction of the Santa Fe line had kept the “Oklahomaists” occupied and hopeful. Though many on the frontier anticipated speedy legislation to follow completion of the road, the news from Washington remained scant on the matter of Oklahoma settlement. Finally in December, the boomer cry of “On to Oklahoma” was again sounded when a fanciful El Dorado newspaper story told of secret plans of some 100,000 men who supposedly were to make a raid into Oklahoma in the early spring of 1888. [4] Coincident to this came the announcement from Washington that an Oklahoma bill was being prepared and would be presented to the House of Representatives by either General James B. Weaver of Iowa or William M. Springer of Illinois. The smoldering coals of boomerism were fanned back to life in January of 1888 when a circular was sent out to some 500 men in Kansas, Missouri, Colorado, Arkansas, New Mexico, Texas, and the Indian Territory calling them to a conference in Kansas City on February 8. Leading the move were W. L. Couch, Samuel Crocker, fiery editor of the boomers’ Oklahoma War Chief newspaper, and former Kansas congressman Sidney Clarke. These boomer loyalists had persuaded a number of important men to sign a circular promoting the meetings, among them being long-time Oklahoma enthusiast Dr. Morrison Munford of the Kansas City Times. [5] The purpose of the affair was to reawaken frontier interest in Oklahoma settlement and to convince Congress of strong popular support for the immediate opening of the Oklahoma lands. Preliminary meetings were held at Caldwell and Arkansas City on February 1 and 3, with Couch and Crocker speaking to turn-away crowds. The boomer leaders were joined on the platform by J. S. Jennings of the Wichita Republic, Judge J. M. Galloway of Fort Scott, and Milton W. Reynolds of Gueda Springs. Reynolds, who was well-known in Kansas journalism as “Kicking Bird,” had only recently taken an active role in the boomer cause, having spoken to a rally at Arkansas City in late January. The Wichita Eagle commented wryly that “Milt Reynolds has ‘jined’ the Oklahoma boomers. That country will now be opened for settlement.” [6] At Arkansas City, Reynolds had issued the warning that “Congressmen and Senators who heed not the mighty voice of the people might as well at once turn up their Congressional and Senatorial toes to the daisies, for the places that know them now will know them no more forever.” [7] A resolution urging immediate opening of the unoccupied lands of the Indian Territory was drafted at the preliminary boomer convention, to be sent to all the Kansas congressmen. Couch, Crocker, Reynolds, Jennings, and Galloway were elected to represent the meeting at the Kansas City conference. Couch and Crocker, along with the old boomer, the long-haired John Furlong of Wichita, were on the front seats in the Kansas City Board of Trade Hall on February 8 to hear the opening speaker state the boomer theme: “Unless some good reason exists why this country [Oklahoma] should remain a home of savages, and a hiding place for criminals; unless there is a good reason for it, the people of the neighboring States have a right to demand the opening.” [8] Couch was called upon to speak. He told the conference that while he favored opening the entire Territory to settlement, he supported the Springer Oklahoma Bill because it would meet with less opposition . . . “and then it is only a question of time until the entire Territory is opened.” [9] One of the invited delegates was Chief John Earlie, whose Ottawa tribe resided in northeastern Indian Territory. When asked to speak, the chief walked to the front of the stage with great dignity. He and his tribe, he said, were heartily in favor of opening all of the Territory to settlement. The Ottawas had already divided up their lands, and he thought it would be better for the Indians and cheaper for the government to do away with tribal relations in the Territory. “I want the Territory opened up,” he told the white audience, “the Indians to mix with the whites, the whites with the Indians, and the Indians to become more and more like the whites.” [10] When the speech making was done, convention delegates drafted a resolution to Congress calling for the speedy opening of the Territory. A delegation which included Couch, Crocker, Clarke, and Munford was elected to carry the resolution to Washington and present it to Congress. Following the convention, the delegation headed for Washington. Munford, who was personally acquainted with President Grover Cleveland, secured an audience with the chief executive for himself and Crocker. [11] The two discussed the Oklahoma question with Cleveland and then made arrangements for the entire delegation to meet with the President. Sidney Clarke did the talking for the group and presented Cleveland with a copy of the “Kansas City Interstate-Oklahoma Legislative Memorial.” [12] This done, most of the members of the delegation left Washington; but Couch, Crocker, and Clarke remained behind to assist in advancing the Oklahoma Bill in the House. There had been several bills for the organization of Oklahoma Territory, as well as numerous petitions and protests, submitted to the first session of the Forty-ninth Congress when it had convened in December 1887. One had been authored by Weaver of Iowa, another by Richard W. Townshend of Illinois, one by Bishop W. Perkins of Kansas, and still another by Senator Charles H. Van Wyck of Nebraska. But it was the bill introduced on January 6, 1888, by Springer of Illinois that was initially debated by the House of Representatives on February 25 and 28. One of the opponents of the bill, Representative George T. Barnes of Georgia, complained of “secret societies with signs and grips and passwords organized for the purpose, ready to rush in as settlers.” [13] He also described the Indian who, with his ear to the ground, listened with dread to the sound of the advancing hosts. Indeed, the Indians of the Territory were listening, and they by no means all agreed with Chief Earlie. On January 31, a delegation of Indian leaders and their attorneys appeared before the House Committee on Territories, which was chaired by Congressman Springer. The spokesman for the Cherokee Nation read a protest against the authority of the United States to enact any kind of legislation relating to the Indian Territory.” [14] Following him was Colonel G.W. Harkins, representing the Chickasaw Nation. Harkins, a man well educated in Eastern schools, eloquently made the point that if the government could throw open Oklahoma then it might well take on itself to do the same for the entire Indian Territory. He told how he had been taken from his wigwam as a boy and sent to one of the white man’s colleges. There he had been initiated into book learning.

But Harkins’s argument failed to deter the committee. On June 25 Springer introduced a revised bill which received a favorable recommendation by the Committee on Territories and went to the House floor for debate. These discussions were held from July 26 through August 30. General Hooker of Mississippi opened with the argument that the bill was in violation of treaty stipulations and that Congress had no power to create a territorial government over any part of the Indian Territory.  On the twenty-ninth, Payson of Illinois offered an amendment to the bill whereby the Oklahoma lands would be open to settlers only under the Homestead Act rather than requiring payment of $1.25 an acre in four installments over a period of three years as required in the original bill. Springer and boomer leaders saw this as a pretext to encourage many to vote against the bill on economic grounds, since the Payson amendment could cost the treasury an estimated $30 million. Anderson of Iowa wished to amend the bill so that every honorably discharged Union soldier could have his land free. [21] The argument over payment continued on the thirtieth with Representative Samuel R. Peters of Kansas contending that under homestead laws speculators could pay their two dollars for land office fees, hold the land for six months or longer, and then sell it at a profit. Nelson of Minnesota issued a warning that the government was being too extravagant with the public domain. The rapid settlement of the Western lands, he said, had enhanced their value, and $1.25 was little enough for anyone, however poor, to pay. [22] Despite all the discussion and debate, the Springer Oklahoma Bill failed to receive action before the legislative session ended. Disappointed but as determined as ever, the boomer leaders headed home, Couch going by way of Iowa to assist General Weaver with his campaign for reelection. It was necessary now to work out new plans for keeping the Oklahoma issue alive and heated in both Kansas and Congress. No one knew better than Crocker how to do that. He persuaded Marsh Murdock, Payne’s old nemesis at the Wichita Eagle who had now swung over to the boomer side on Oklahoma settlement, to call another interstate Oklahoma convention for November 20 in Wichita. The biggest names in the Oklahoma movement were brought forth to give the meeting special drawing power – Springer of Illinois, Mansur of Missouri, and Weaver of Iowa. [23] Hundreds of delegates from over Kansas and surrounding states arrived at the Wichita train depots and later filled the Crawford Opera House “to suffocation” to lustily cheer their congressional champions and boom Oklahoma settlement. In the afternoon, Springer addressed the convention. He said there were two main barriers to the settlement of Oklahoma. One was the complications growing out of Indian titles to the land, those being of a “very shadowy and unsubstantial character.” Since the government had declared its intention of settling friendly Indians on those lands, Springer felt it was of utmost importance for early passage of the Oklahoma Bill before “complications and embarrassments … will confront us.” [24] Springer, who had never been to the Indian Territory, then spoke of the great cattle syndicates who leased some six million acres of the Territory’s grazing lands. “The time for their occupancy is short,” he insisted, “and the cattle kings must go.” But the main thrust of his oration was that “There is an irrepressible conflict between barbarism and civilization. The result of that conflict is not a matter of doubt. No portion of this continent can be held in barbarism to the exclusion of civilized man.” [25] Weaver told the crowd that he had long since decided that white men had rights as well as black or red men and insisted that the interests of both Indians and whites demanded passage of the bill. Mansur pointed to over 365 murders which he said had been committed in the Indian Territory during the past year, concluding that a sort of sentimentality in the East and South against the bill was evaporating in the light of such facts. A resolution was drafted calling upon the President of the United States to exercise his authority in support of opening Oklahoma. [26] Once again Couch, Crocker, and Clarke were appointed to go to Washington and present the document in the interest of the bill. “Oklahoma Harry” Hill, an original Carpenter and Payne boomer and now a successful Wichita horse and mule trader and stage line owner, and H. L. Pearce of Wichita were named to raise the $1,500 required to defray the expenses of the committee. Not mentioned at the Wichita convention but of great significance to the cause of opening Oklahoma to settlement was a measure passed by the legislature of the Creek Nation in late October approving the sale of their interest in the Oklahoma lands. Such a sale would do much to clear away the last vestiges of Indian claim to the contested area. [27] While the boomers were adamant in their charges of a cattle syndicate lobby in Washington, the cattlemen claimed otherwise, insisting that they had no lobby there at all. The Cherokee Strip Live Stock Association listed a number of cattle companies, however, in which congressmen were known to hold an interest. Lobby or not, there was always the noticeable presence of cattlemen on Capitol Hill whenever the Oklahoma Bill was being debated. [28] There was no question about the lobbying efforts of the boomers. The delegation chosen at Wichita entrained immediately for the capital in order to be there when Congress reconvened in December 1888. Their efforts were rewarded on February 1, 1889, when the Oklahoma Bill was passed by the House of Representatives with a 147 to 102 vote. [29] It was not an easy victory, however, for opponents of the measure fought back with every parliamentary device they knew to delay the final vote. Weaver and Springer were given much credit for their floor fight, while Couch, Crocker, and Clarke “labored in and out of season for the advancement of this great measure.” [30] But the fight was far from won. The Springer Bill now went to the Senate where it was debated on February 5. Senator Chase of Rhode Island immediately branded the bill as “a well laid scheme to encroach upon Indian rights and rob them.” Senator Morgan of Alabama defended the bill as going further in recognition of Indian rights than was justified by law. Morgan also brought forth a new argument in favor of opening Oklahoma. He charged that a “very reprehensible and dangerous state of affairs existed under the communistic system of the Indian Territory and that a Federal court was needed to restore law and order within the Territory.” [31] The Springer Oklahoma Bill was referred to the Senate’s Committee on Territories, while the Kansas boomers and the pro-Oklahoma congressmen held a strategy meeting at the Territorial Committee room of the House on February 12. All were anxious that the bill be returned to the Senate in time to make arguments for it. [32] But the boomers and their friends in Congress could but sit and fume while the cattlemen and their lawyers thronged the Senate Public Lands Committee in their efforts to defeat the bill. [33] Milton Reynolds and other Kansas supporters arrived in Washington to help as best they could. Finally on February 18 the Committee on Territories reported the Oklahoma Bill to the Senate favorably without amendment. There was a minority report, however, and rumors circulated that a substitute bill would be submitted by the opposition. Even as the bill was waiting to be called up, cession agreements with the Creek and Seminole Indians were being considered by the House Indian Affairs Committee. Both of those tribes had indicated they were willing to sell their remaining rights to the land to allow Congress to use it for purposes other than for settlement by “other Indians or freedmen,” as their 1866 treaties had specified. [34] Another mass convention of Oklahoma boomers was held at Arkansas City on February 20, 1889, and a resolution was drafted and wired to senators John J. Ingalls and Preston B. Plumb of Kansas, urging them to use every effort to secure the speedy passage of the Oklahoma Bill. But in Washington it appeared that opponents of the bill would be successful in delaying a vote until Senate adjournment. Proponents now decided upon a clever counteraction. The annual Indian Appropriations Bill was being considered in the House. Representative Samuel W. Peel of Arkansas, chairman of the Committee on Indian Affairs, on February 27 submitted an amendment – Section 12 – to the appropriation bill which provided $1,912,952.02 to pay for final rights to the 2,370,414.62 acres of land ceded by the Seminoles and Creeks. Springer then added Section 13, authorizing the President to open the lands to settlement through issuance of a proclamation. Representative Thomas Ryan of Kansas added another clause authorizing the establishment of two land districts and offices within the cession area. [35] These House-inserted clauses were defeated in the Senate, however, and it was necessary to order a joint Senate-House conference on the matter. There Senator Bishop W. Perkins of Kansas made a determined stand for the amendments and succeeded in getting them restored to the bill, which now passed the Senate. Thus the Oklahoma lands were finally placed into the public domain preparatory to a presidential proclamation opening them to settlement. The successful passage of this historic rider, however, depended upon some practical action outside of Congress, as it happened. [36] When the rider clauses were finally drafted in makeshift form, approved by the Senate-House committee, and ordered printed, General Weaver came to Crocker and asked how quickly he could get the bill additions into print. They were running out of time. The War Chief editor took a glance at the handwritten riders. “Well,” he said, “if I don’t have too far to go to find a printing office, and with enough help, I can have this bill printed and in your hands in an hour. How far away from here is the printing office?” Weaver told him that it was nearly a mile down Pennsylvania Avenue from the capitol where they were. Crocker took the bill, promising to get it printed and back just as fast as he could. An attorney for the Santa Fe Railroad was standing with the two men, and he handed Crocker a dollar for fare on the horse-drawn streetcars of Washington. “Now, Mr. Crocker,” the lawyer said, “fetch that bill to us as quick as you can. Chairman Springer wishes to introduce it before adjournment.” The portly Crocker hurried out and caught the first streetcar to the printing office. There he quickly explained to the printer the importance and urgency of getting the bill printed immediately, suggesting that it be divided among a number of compositors in order to expedite that phase of the procedure. This was done, and the entire manuscript was soon set in type and on the press. Grabbing the pile of printed pages, Crocker ran out of the printing shop to catch a streetcar back to the capitol. But when he reached into his pocket for the dollar bill given him by the Santa Fe attorney, he discovered that he must have lost it in his rush. Crocker dug frantically through his pockets and finally came up with a nickel for his fare, allowing him to make it back to where Weaver and the others were waiting impatiently. The makeshift bill was introduced and successfully passed, being signed into law by President Grover Cleveland on March 2, 1889. The riders to the Indian Appropriation Bill did not provide for the establishment of a new territory or even mention the name of “Oklahoma.” As an expedient it merely provided that the lands ceded by the Seminole and Creek Indians should be considered as public domain and be opened to settlement on a date to be set by a proclamation of the President of the United States. This action would be left to the newly-elected President, Benjamin Harrison, who was to take office on March 4, 1889. And so it had finally come to pass. It had taken a full decade of intrusion, agitation, promotion, and political maneuvering to bring it about. The movement for which Boudinot had first voiced the premise, which the Kansas City Times and Carpenter had launched in the spring of 1879, which David Payne had taken up as his life cause in 1880, and which W. L. Couch had carried on after Payne’s death in 1884, had been crowned with success. The first land of the Indian Territory – and no one had any doubt that it would be only the first of such openings within this country which had been promised so faithfully to the Indian – would soon be settled by non-Indians. CHAPTER I This Coveted Land 1 Congressional Record, Vol. XIX, July 26. 1888, p. 6870. 2 Cited by Winfield Courier, September 2, 1886. The railroad survey into the Oklahoma country had been preceded by a private survey out of Arkansas City for a wagon road through the Otoe Agency at Red Rock to Council Grove in October 1885. Arkansas City Traveler, October 28, 1885. 3 August 18, 1886. 4 Ibid., December 16, 23, 1887. 5 Wichita Eagle, February 3, 1888. 6 Ibid. 7 Kansas City Gazette, February 3, 1888. 8 Ibid., February 9, 1888. 9 Ibid. 10 Ibid. 11 Dan W. Peery, “The First Two Years,” The Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. VII, No. 3 (September, 1929), p. 281. 12 Ibid. 13 Congressional Record, 50th Cong., 1st sess., 1887-1888, Vol. XIX, p. 1564. 14 Kansas City Gazette, February 1, 1888. 15 Ibid., February 2, 1888. 16 Congressional Record, Vol. XIX, p. 6870. 17 Ibid., p. 6875. 18 Kansas City Gazette, July 28, 1888. 19 Ibid. 20 Congressional Record, Vol. XIX, pp. 8051-8058. 21 Ibid., pp. 8082-8087; Kansas City Gazette, April 29, 1888. 22 Congressional Record, Vol. XIX, pp. 8116-8120; Kansas City Gazette, August 30, 1888. 23 Wichita Eagle, November 23, 1888. 24 Kansas City Gazette, November 21, 1888. 25 Ibid. 26 Ibid. 27 Ibid., October 22, 1888. 28 Joseph B. Thoburn and Muriel H. Wright, Oklahoma, a History of the State and Its People, Vol. II, pp. 529, 533. 29 Congressional Record, 50th Cong., 2nd sess., 1888-1889, Vol. XX, pp. 1400-1402. 30 Kansas City Gazette, February 2, 1889. 31 Ibid., February 6, 1889. 32 Ibid., February 13, 1889. 33 Ibid., February 16, 1889. 34 Ibid., February 21, 1889. 35 Ibid., March 4, 1889. 36 Dan W. Peery, “Colonel Crocker and the Boomer Movement,” The Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. XIII, No. 3 (Fall. 1935), pp. 286-287. |

Per the above, the treaties with the Seminoles and Creeks were renegotiated and the previous treaty conditions that the areas be used to locate other tribes or freedmen to those areas were removed thus placing the earlier cessions in the public domain, and the political debate concerning the settlement by non-Indians of the Unassigned Lands was done.

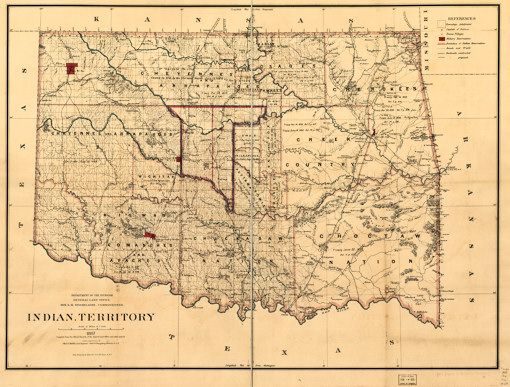

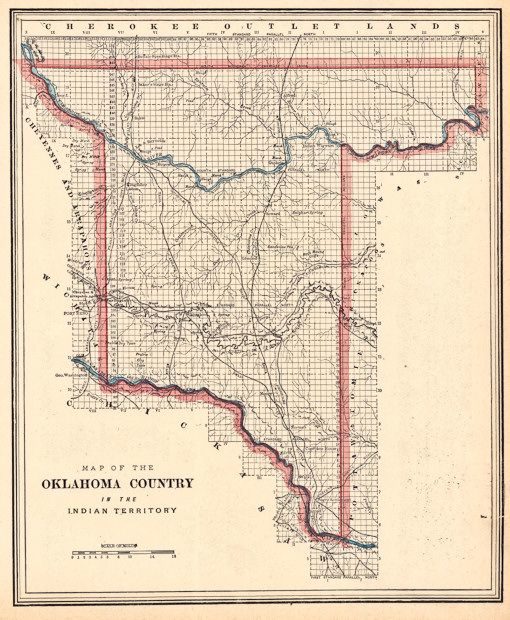

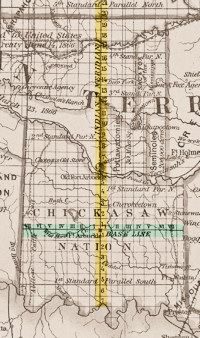

Location & Size. Where was it? The 1887 Indian Territory map prepared by the U.S. Department of the Interior, General Land Office (and thanks to Greg Sullaway of The History Exchange for pointing me to this map) shows the area being fussed about in Congress nicely. This map was found at the Library of Congress website, and its notes state, about the map, that “It has also been annotated to illustrate the boundaries of the formation of Oklahoma Territory within the Indian Territory” and was located in the “papers of President Benjamin Harrison.” The north/south Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe railroad, completed in 1887, is shown (although the part from Purcell to Texas was then the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe railroad). For a 6,000 pixel wide view of this map, click here. For a 2,000 pixel wide view, click the image below.

Note that this map repeats the error of showing the Cherokee Outlet as Cheyenne and Arapaho territory, which it never was.

How big an area was it? As to the distance around the perimeter, I haven’t seen an actual mileage count but my eyeball counting of section lines along the perimeter of the 1887 Cram map of “Oklahoma Country” — the Unassigned Lands — (to be discussed shortly) comes up with a border of about 325 lineal miles, more or less. It encompassed nearly 2-million square acres, which, doing the math, is about 3,125 square miles. However, in his essay at page 124 of Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (2006), John R. Lovett puts the number at “roughly 2,950 square miles.”

Why would this map have been located in the papers of President Harrison? As said by Angelo C. Scott in his Story of Oklahoma City (Times-Journal Publishing Co. 1939),

Let us now go back to some seven weeks before the opening day. On March 2, 1889, the Indian appropriation bill was passed with a “rider” opening to homestead settlement about two million acres of land known as Oklahoma. On March 3 President [Grover] Cleveland approved the bill, and on March 23 President [Benjamin] Harrison issued a proclamation announcing April twenty-second as the opening day and twelve o’clock noon the earliest hour at which one could legally enter the land. ¶ And it was truly just the “land.” It was not a territory; it was not a state; it was just “the Oklahoma country.”

Quite possibly, someone had marked up the map in Grover Cleveland’s presidency or in the earliest days of Benjamin Harrison’s to note exactly what area was included in this unprecedented Land Run that was about to begin. A cropped portion of the above map, but with me adding yellow color for what would eventually become Oklahoma County, is shown below.

The map’s legend, easily seen in the upper right corner of the 6,000 pixel wide version, shows 4-rectangular-dots as representing “Towns, Villages.” Note that the map includes a cartographer mistake — Wellston is mislocated. Wellston is shown just slightly east of the Indian Meridian whereas, in fact, it is about 10 miles east of that location and that was a common mistake in Rand McNally and other maps made during this time period. The area marked as “Timber Res.” was originally the location of Jesse Chisolm’s trading camp which became a timber reservation for Ft. Reno located several miles west in Canadian County. Today, we know this area as the Council Grove township to Oklahoma County. Above, I’ve taken the liberty of highlighting the eastern 144 square miles of what would become Oklahoma County even though it was not within the Unassigned Lands area. In the Oklahoma County area, Oklahoma and Edmond stations are present and as is “Verbeck” south of the Oklahoma County area. It would later become “Moore” before the Land Run occurred.

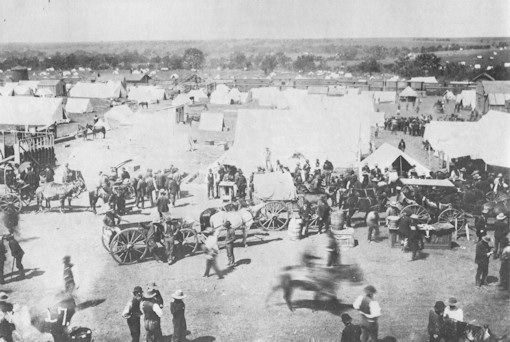

A Note About The Ewing Townsite. The above map also shows “Ewing” as a “town or village.” It is curiously interesting that, in this 1887 federally prepared map, Ewing is shown for some unknown reason since Ewing was not then a town — even though it does have a historical significance. In April 1880, David Payne had led a group of 21 Boomers into the Oklahoma County area and laid out a town which Payne called Ewing, probably named for fellow Kansan Gen. Thomas Ewing who had Payne’s admiration and respect as well Payne’s support when Ewing sought to become a U.S. Senator. Following Payne’s attempted establishment of Ewing, he and his group were forcibly removed back to Kansas after being detained at Ft. Reno for a short time. In its discussion of the Boomer Movement, OHS’s Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture shows the photograph below accompanying its discussion of Ewing.

Certainly, the wagon train shown is not specific to this particular foray — there are clearly more than 21 people represented in that caravan — but is instead intended to show an example of Payne’s Boomer activity. Payne returned to Ewing in July 1880, this time with a larger group. The group was again returned to Kansas but Payne was taken to Ft. Smith to face charges. What charges? The OHS article notes that Pres. Rutherford B. Hayes issued a proclamation on April 26, 1879, that forbade unlawful entry into Indian Territory. The OHS article says,In March 1881 the government prosecuted Payne at Fort Smith, Arkansas, before Judge Isaac Parker, who ruled against the Boomer leader. The only legal action that could be brought against Payne was a federal law levying a thousand-dollar fine for a second intrusion into Indian Territory. Payne, however, had no money or property against which the fine could be assessed. News of his arrest only made him more popular on the frontier and further publicized his cause.

The Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (2006) also shows Ewing at its map drawing of the Unassigned Lands at page 125, a crop from which is shown at the right. Note, however, that this map locates Ewing south of Oklahoma station, at variance from the 1887 map which locates it southeast of Edmond and northeast of Oklahoma station, south of a bend in the North Canadian river, the latter probably being correct. See the additional discussion in Boomers, Again, below.

Given this background, the inclusion of Ewing in the 1887 federally prepared map struck me as curious, to say the least. Ewing is mentioned again, below.

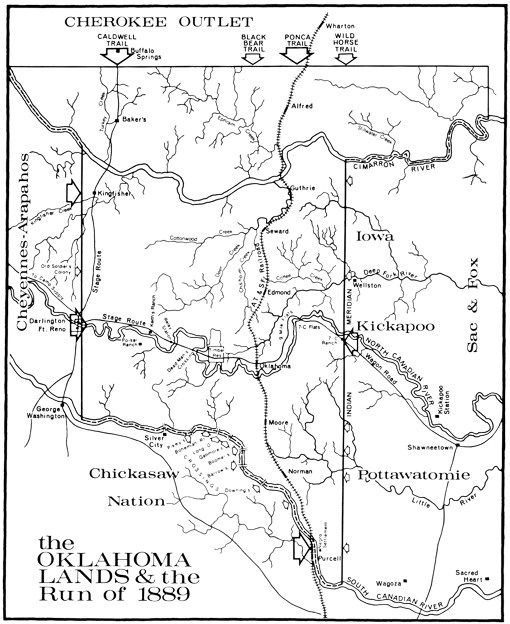

Of the cartographers whose work product I’ve had the occasion to see in my present and earlier reviews of Oklahoma maps, without a doubt the best work was done by George Franklin Cram of Chicago. The map shown here is from Cram’s Unrivaled Atlas of the World published in 1889. Have a look at the precise detail of this map of “Oklahoma Country,” below. The map was found at the University of Alabama’s historical maps area, and that website contains many Indian Territory and/or Oklahoma Territory (and other Oklahoma) maps. Unfortunately, the website does not give an option to download an entire high resolution file like the Library of Congress website does — or if it does, I didn’t find it. If one wants to save a high resolution image one must copy and save various segments of a map and then piece them together in one’s graphic software. The fabulous map below represents a quilting together of 40 such pieces.

Each horizontal and vertical line is one mile apart — section lines — and horizontal and vertical legends associate each such mile with a number. Horizontally and at the top, the numbers, east to west, are 44 through 125; vertically, the numbers are, beginning at left top, 88-152, and, beginning at right bottom, 1-40. Quite possibly, an accompanying document not shown in the map identifies what these legend numbers mean, or perhaps they are more akin to mile markers we see on interstate highway routes today. If this map was intended to be used by land runners, the numbers might relate to stakes or markers placed in the Unassigned Lands area prior to the Land Run. Or it may be that this map was prepared after the April 22, 1889, Land Run.

Whichever if any of the above possibilities be true, a great amount of exact detail is included in the map — names and locations of creeks, trails, stage lines, town and other benchmarks and points of reference. Whether the inclusion in the map of an additional six miles east of the Indian Meridian represented planning, prophesy, or coincidence, one is left to guess. As a matter of fact, that additional six mile area would be assimilated in Oklahoma Territory in later land runs, as we shall shortly see.

In the above map, the highlights and crop below show the area covered by Oklahoma County, in 1889, and now.

|

|

THE APRIL 22, 1889, LAND RUN SETTING. At what border points did the land-runners, many by rail, others by wagon or buggy, or horseback or on foot, enter the Unassigned Lands? What good and bad experiences were there? How numerous were the “Boomers” and “Sooners” and how did lawmen and tax collectors attempt to gain an advantage, and did they? Although I’ll mention others in this description, by far the most thorough and useful resource I’ve located is the one previously quoted from, Stan Hoig’s The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889. The book is out of print and is sometimes but not always pricy at Amazon.com and elsewhere, and I heartily recommend this book.

Hoig begins the book with his own rendering of a map and the similarities between his hand-drawn map and the Cram map, above, are obvious.

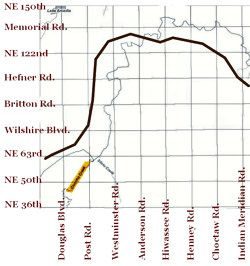

The trails and detail drawn from the Cram map are unmistakable — except that Cram did not locate Wellston incorrectly like the above drawing does — I’ve shown the correct location for Wellston in the annotated map below — about 10 miles east of the Indian Meridian. But, Hoig also adds points of ingress, major and minor, and, in his text, adds details associated with each particular point of entry. A cropped area from his map showing the Oklahoma County area is presented below — together with some color that I’ve added for emphasis. The yellow portion was not part of the 1889 Land Run but would come later; the green areas show points of ingress. The principal trails are the same as were contain in Cram’s 1889 map.

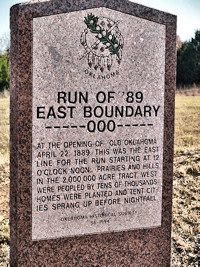

The ingress arrows outlined in black are Hoig’s — the arrows without a black outline are mine. A historical marker shown at right is present along the old Route 66 and marks the eastern boundary, near the small green arrow where Hoig incorrectly shows Wellston. If properly located, the monument would be exactly on the north/south Indian Meridian.

The ingress arrows outlined in black are Hoig’s — the arrows without a black outline are mine. A historical marker shown at right is present along the old Route 66 and marks the eastern boundary, near the small green arrow where Hoig incorrectly shows Wellston. If properly located, the monument would be exactly on the north/south Indian Meridian.

The Law. Two acts of the 1889 session of Congress formed to make the whole, on March 1 and March 2. The first dealt with the Creeks and the second with the Seminoles. The 2nd act also blended the acts together for purposes of uniformity in application — so when you see elsewhere that on March 2, 1889, federal legislation was the date of congressional law which opened the Unassigned Lands to non-Indian settlement, understand that the “March 2” legislation (Seminoles) includes the March 1 legislation (Creeks), as well. To read both 1889 statutes in their original form, click here.

Section 13 of the March 2, 1889, federal law provided, in part, “. . . but until said lands are opened for settlement by proclamation of the President, no person shall be permitted to enter upon and occupy the same and no person violating this provision shall be permitted to enter any of said land or acquire any right thereto.” In the same legislation, the provisions of the Homestead Act of 1862 were declared applicable to this Land Run. Part of that act provided,

That any person who is the head of a family, or who has arrived at the age of twenty-one years, and is a citizen of the United States, or who shall have filed his declaration of intention to become such, as required by the naturalization laws of the United States, and who has never borne arms against the United States Government or given aid and comfort to its enemies, shall, from and after the first of January, eighteen hundred and sixty-three, be entitled to enter one quarter-section or a less quantity of unappropriated public lands, upon which said person may have filed a pre-emption claim, or which may, at the time the application is made, be subject to pre-emption at one dollar and twenty-five cents, or less, per acre; or eighty acres or less of such unappropriated lands, at two dollars and fifty cents per acre, to be located in a body, in conformity to the legal subdivisions of the public lands, and after the same shall have been surveyed: Provided, That any person owning or residing on land may, under the provisions of this act, enter other land lying contiguous to his or her said land, which shall not, with the land so already owned and occupied, exceed in the aggregate one hundred and sixty acres.

Similar to the 1889 Congressional enactment, President Harrison’s March 23 proclamation expressly warned that “no person entering upon or occupying said land before said hour of 12 o’clock, noon, on the 22nd of April A.D., 1889, hereinbefore fixed, will ever be permitted to enter any of the said lands or to acquire rights . . .” The precise meaning of the phrases used would take lots of litigation and even a U.S. Supreme Court decision to figure out. In Berlin B. Chapman’s, “The Legal Sooners of 1889 in Oklahoma,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 35, p. 382, 383-384 (Oklahoma Historical Society Winter 1957-58), the author stated,