Go To Trains Part 2 Go To Trains Part 3

Go To Trains Part 2A Go To Trolleys Part II

From Whitstle Stop Trains

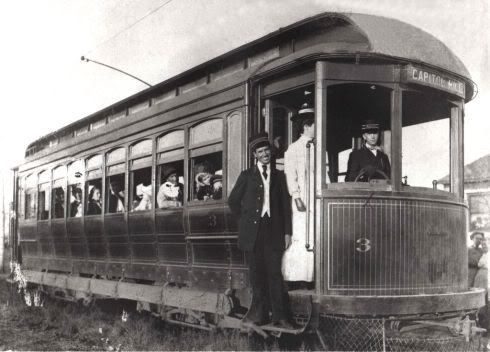

On February 6, 1903, the Oklahoman headline read, “Car Service Next Monday,” and indeed it was. The article tells a brief story about a “Boomer” who had witnessed a trial run. He had sighted “the modern electric flyer” moving north on Broadway, and “His amazement was apparent.”

Leaning forward, with his hands thrown out, sombrero tilted back, this survivor of the picturesque band of intrepid adventurers which effected the opening of Oklahoma to white settlement stood with his eyes riveted upon the receding car until it disappeared fro view over the crest of the North Broadway divide, when, straightening up and heaving a great sigh, he exclaimed:

“Well, by thunder! They’ve sure got them cars toted by lightnin.”

With this solitary comment the” boomer” entered the nearest saloon and quieted his nerves by swallowing a four-finger quantum of fire water with a toast to “civilization and the memory of David Payne.”

The article noted that, initially, there would be two lines, the University Line (South Broadway to University Heights) and the Maywood Line (Stiles Park to Colcord Park and Delmar Garden). If that be so, the routing would quickly change … When Oklahoma Took The Trolley says that, “The original plan called for a four-mile double-tracked loop around the downtown district on Main Street and Grand Ave., but by February 7, 1903, cars were operated on a more elaborate system including a line from Choctaw and Broadway north to 13th and Broadway; a line from Main and Broadway west to Western; a line from Reno and Harvey north to Fourth, west to Walker and north to 13th, and a line from Stiles Park from Fourth and Broadway via Harrison Ave.”

Whichever report is more correct, Trolleys Part 1 traces the beginnings and the development of trolleys, “traction” rail, in Oklahoma City. My sources are (1) the Oklahoman’s archives, (2) When Oklahoma Took the Trolley by Allison Chandler and Stephen D. Maquire (Interurbans 1980), (3) Born Grown by Roy P. Stewart (Fidelity Bank 1974), (4) Oklahoma City: Land Run to Statehood by Terry L. Griffith (Arcadia Publishing Co. 1999), (5) Oklahoma City: Statehood to 1930 by Terry L. Griffith (Arcadia Publishing Co. 2000), (6) Oklahoma County: Heart of the Promised Land by Bob L. Blackburn (Windsor Publications 1982), (7) Vanished Splendor (I) by Jim Edwards and Hal Ottaway (Abalache Book Shop Publishing Co. 1982), (8) Vanished Splendor II by Jim Edwards and Hal Ottaway (Abalache Book Shop Publishing Co. 1983), (9) Historic Photos of Oklahoma City by Larry Johnson (Turner Publishing 2007), (10) this nice article at the Metropolitan Library System (you may need to press your “refresh key” … F5 … after clicking the link), and (11) Oklahoma City’s First Mass Transit System: Who Brought the Streetcars for People to Ride? by Kim K. Bender (Oklahoma Historical Society, Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 72, No. 2, Summer 1994). Occasionally, I found inconsistencies in various reports and, sometimes, errors, and I’ll note these as it becomes relevant. Image sources are noted with each picture but most are from a wonderful CD produced by Whitstle Stop Trains located at 1313 West Britton Road in Oklahoma City.

The “ending” point of Trolleys Part I is a bit blurry, but, generally, it ends around 1910-1913 but excludes the 1911 strike and interurban development – that will be covered in Trolleys Part 2 long with the 1923 floods, economic ups and downs, lots more pics along the way, and the end of the line in 1947. I also expect to edit this post from time to time.

In this post, click on any image for a larger view.

THE BACKGROUND. If interstate steam locomotives and trains were instrumental in placing Oklahoma City “on the map,” local electric trolley and interurban railways were what helped the Oklahoma City “map” grow! Aside from interstate and intrastate steam engines, Oklahoma City was born in the days of horses, wagons, and buggies, and not until the trolleys arrived did Oklahoma City acquire the mobility to enable expansion beyond its then small geographical turf. As said in the Metropolitan Library System article linked above,

At this [1903] time Oklahoma City was a town of about 14,000 people crowded into about four square miles – bounded by Western Ave. on the west, Eastern Ave. on the east, Thirteenth St. on the north and the river on the south.

Oklahoma City’s trolley and interurban system (using the phrase loosely) was not funded by public funds … it was funded by capitalists who poured millions of dollars into developing and maintaining the system. Was it intended to make a profit? Sure … but it would take a pretty dim-witted economist to think that over time that the magnitude of investment would reap any significant return on even a magnificent number of riders paying a 5 cent fare (the rate for a very long time). If they had any shortcomings (as all of us do), one would be hard-pressed to argue that the likes of Anton Classen and/or John Shartel lacked business savvy when it came to making a buck, and lots of them!

These guys made their big bucks by virtue of their unofficial role as “city planners.” After obtaining a franchise from the city, it was pretty much up to a company to develop the lines as they saw fit (in the absence of a city council’s prohibition of placing track on a particular street). If they knew what they intended, land, and lots of it, could be acquired before the line was actually developed … of course, by other companies who not coincidentally were at least partially owned by the same principal stockholders of the traction lines themselves. And, what about construction? The traction companies did not “build” the tracks … that work was contracted out … and guess who to? That would be to yet another company whose stock was at least partially owned by the stockholders in the trolley company. And, what about financing the nice new house away from downtown … mortgage and/or construction lenders were needed for that, and … same story.

Now, please don’t take this as criticism of the capitalists … and I do not doubt that some if not all of them understood and followed the concept of enlightened self-interest, Alexis de Tocqueville having coined that phrase many years earlier. These early day capitalists did a heck of a lot of good for the city, including lots of trees being planted as well as providing inexpensive transportation for the public good. And, let’s not forget that they gambled a bunch of money that Oklahoma City would become the metropolitan area that they worked at it becoming. But, while one might wax nostalgic about good things gone by, it would be a great mistake to shed a tear for the capitalists ultimately not being able to make a profit on the trolley system as times changed … as they would after a good bit of geographic expansion occurred, and as they would after automobiles became available and affordable. Many made enormous profits in the by-products of trolley development which were not lost when the trolley system faltered or did not succeed.

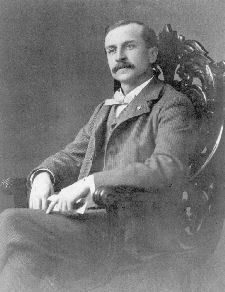

Anton Classen & John Shartel. The names most often associated with Oklahoma City’s traction “system” have already been mentioned: John Shartel (left below) and Anton Classen (right). Shartel moved from Kansas to Guthrie in 1889 and then to Oklahoma City in 1898. He was a teacher by trade, then “read law” to become a lawyer before coming to Oklahoma. He died in April 1926 during a period of ORC controversy. Classen, born in 1861, was an Illinois native, left his family’s farm at the age of 16, obtained a law degree at the University of Michigan in 1887, and homesteaded near Edmond. In 1897 he was appointed receiver for the U.S. Land office in Oklahoma City and in 1901 quit that job to form his own land company, the Classen Company. He served three terms as president of the Commercial Club, predecessor to the Chamber of Commerce. He died in December 1922. It is said that of all the early-day Oklahoma developers that Anton Classen had the most vision of what the city could become.

In 1901, the Metropolitan Railway Company was formed, the stock being owned John Shartel, among others, and the company was granted a franchise in early December 1901.

In 1901, the Metropolitan Railway Company was formed, the stock being owned John Shartel, among others, and the company was granted a franchise in early December 1901.

In late December 1901, Harold Berry, a New York investor, had been granted a franchise by the city. However, in February 1902, Anton Classen purchased this franchise from Berry. Bender’s article opines that, “Classen and Shartel probably conspired from the beginning to form a single franchise after buying out Berry’s interest to establish local control.”

In late December 1901, Harold Berry, a New York investor, had been granted a franchise by the city. However, in February 1902, Anton Classen purchased this franchise from Berry. Bender’s article opines that, “Classen and Shartel probably conspired from the beginning to form a single franchise after buying out Berry’s interest to establish local control.”

In March 1902, Classen surrendered his franchise to Shartel on “condition that Metropolitan build and maintain an electric railway line to the northwest part of the city where he possessed considerable land holdings,” according to Bender, who adds, “Shartel also agreed to continue using the Metropolitan Construction Company, a company Classen controlled, as the principal contractor for the Metropolitan Railway Company.” Vastly oversimplifying, another entity, the “Oklahoma City Railway Company,” wanted to build a line south from Britton but it was unable to obtain a franchise to enter Oklahoma City. A merger occurred between Metropolitan and the latter line with the surviving name being the “Oklahoma City Railway Company,” and, in 1907, it reorganized again becoming the “Oklahoma Railway Company.” Through this process, Classen and Shartel remained the dominant owners. For much greater detail, see the very excellent article in a large PDF file by Kim A. Bender, the best that I’ve seen on these and other inner workings of the traction companies during the early 1900s.

Other Players. Although Classen and Shartel dominated and eventually controlled the trolley market in Oklahoma City, others were on the scene, as well. For example, William Harn (who donated the land that the State Capitol sits on) operated a small line, the Capitol Traction Company, which passed by the State Capital when it was done and also a couple of lines that served northeast Oklahoma City. But, it was C.E. Patterson that made the news. Had I not been scouring through the Oklahoman’s archives during this early period, I’d have missed out on the fun since (but for some reference in Bender’s article) the topic is not covered in the literature that I’ve referenced at the top of this post.

Commonly known as “The Patterson Line,” but also as the “Oklahoma Traction Company,” the “Oklahoma Interurban Traction Company,” and perhaps some other names I’ve missed, Patterson had been granted a franchise in 1905 to construct and operate lines in certain areas in Oklahoma City and, by the time 1909 rolled around, he had done a few … I’m not certain of this, but I think some lines in the Capitol Hill area and to Packingtown … the writers aren’t very precise when describing the original owners of each of the lines and the Patterson lines are not mentioned at all except in Bender’s article.

In any event, Patterson wanted to expand and apparently his original franchise inhibited that. He said that he wanted to build interurban lines to both El Reno and Shawnee, and he was certainly not the first to advocate either of the lines — the Oklahoma Railway Company, as well as others, had been talking about doing that for several years. In early 1909, Patterson circulated a petition calling for an initiative (referendum) vote on whether his franchise should be expanded and in March Mayor Scales determined that the petition had sufficient signatures to put the matter to a vote … a mini-train war was on!

The contestants were Patterson in one corner, and the Oklahoma Railway Company (Shartel & Classen), the Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce, and the Oklahoman in the other. And, they came out swinging!

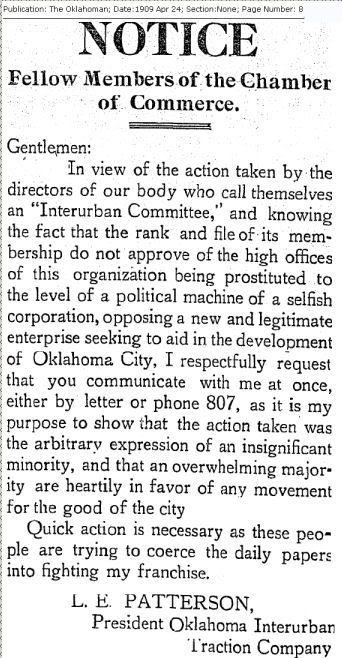

Patterson’s referendum petition did not expressly mention anything about building interurban lines … but it would grant his company the right to construct lines within Oklahoma City which would facilitate the development of interurban routes — and which would place the Patterson Lines in direct competition with the Oklahoma Railway Company within the city proper. More, even though the Oklahoma Railway Company was said to be “friendly” with the El Reno Interurban Company (it served El Reno and Yukon) and the two companies had plans for an El Reno to Oklahoma City interurban line, that had not occurred. Just a few months earlier, the Chamber had put up $50,000 to help make that happen. The “Interurban Committee” of the Chamber had met at the Savoy Restaurant on April 21, according to the April 22 Oklahoman, and passed a resolution opposing the granting of “blanket” franchises to street car companies, which meant, the Patterson Lines. The “Interurban Committee” ran this ad in the April 23 Oklahoman warning voters about the Patterson proposal:

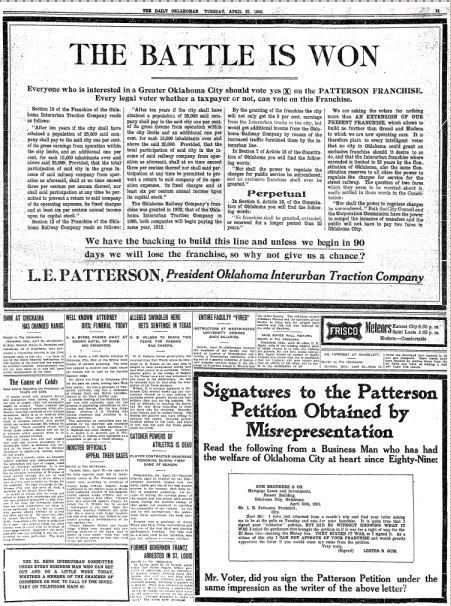

It was repeated on April 24. Patterson’s reply came on that day, also …

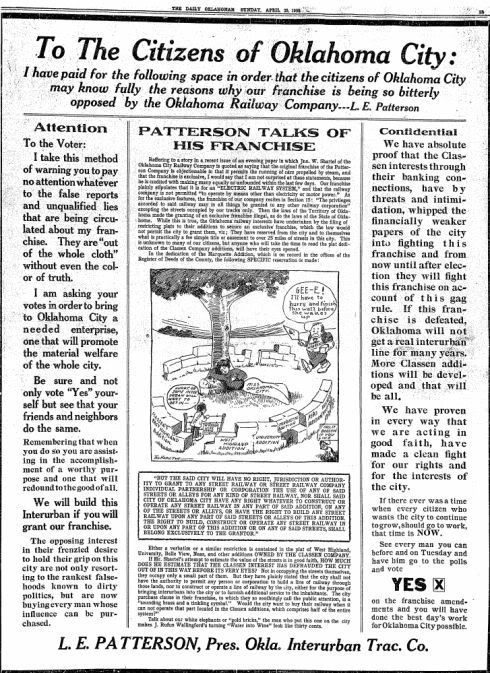

… and the next, on April 25 …

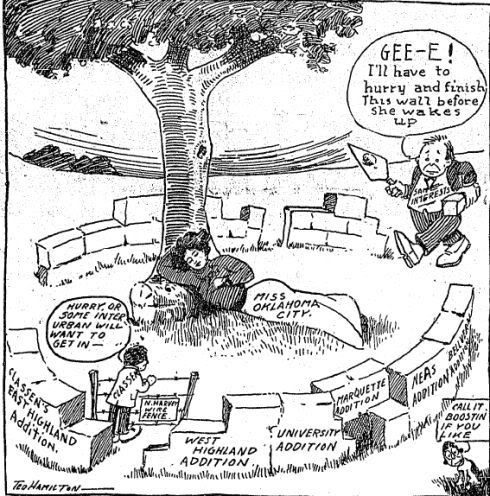

… check out the cool cartoon …

… and both sides had ads on April 27, election day …

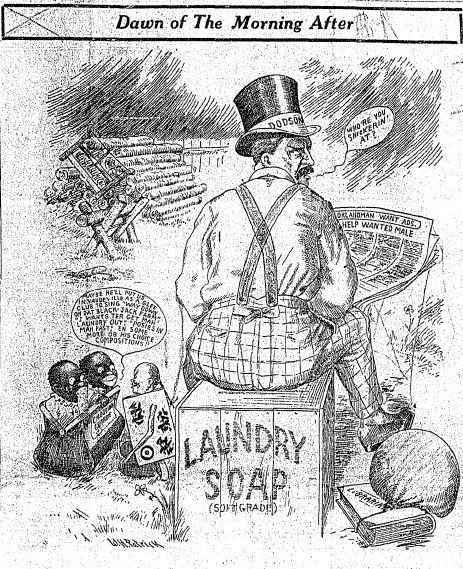

Page 1 of the April 27 Oklahoman contained a box in the lower left corner urging the voters to vote “No” on the franchise. But what is more interesting on page 1 has to do with the mayoral election between Mayor Henry Scales and his principal opponent, one George Dodson who, judging by the Oklahoman’s front-page political cartoons, must have had Guthrie roots. Dodson had apparently incurred organized labor’s ire by having the temerity to use non-union labor to construct a four-apartment-flats project in Oklahoma City — and, recall that, in these days, the Oklahoman was a newspaper that identified itself with Democrats and labor, not with Republicans and capitalists.

One of the “fun” things when researching the Oklahoman’s archives are the occasional items found which have nothing to do with what is being researched, and the Oklahoma’s caricatures of Dodson on the front pages of its April 27 and April 28 editions say a heck of a lot about the racial insensitively which was apparently commonplace in this time. Have a look …

Front Page on April 28, Dodson Having Lost the Election

Back to topic. Notwithstanding his formidable opposition, Patterson won the election by 506 votes, 2,866 to 2,360. But, what did that “victory” mean for the development of either trolley lines in the city or interurban lines anywhere? Not much, really. Patterson’s attempts to construct lines on streets the city had “restricted” (e.g., Robinson Avenue) or elsewhere were generally thwarted one way or another … even though he may have managed a few. But, after litigation resulted in unfavorable results in local courts and the state Supreme Court on at least one occasion, in the end, he threw in the towel (my conclusion) and on October 21, 1913, he sold his lines to the “North Canadian Valley Railroad Company” — which, not uncoincidentally, was headed by none other than John Shartel! The October 22, 1913, Oklahoman carried the story: “Patterson Line Sold To Shartel.” The story says,

The purchase of the Patterson street railway lines by the North Canadian Valley Railroad Company, with John W. Shartel at its head, will mean the end of the war between rival companies, but will not lend toward the construction of any new lines in the city. Mr. Shartel has stated that he bought the Patterson line to give him an outlet for the line he contemplates building east to Shawnee. Within two or three weeks he expects to have connections made between the Patterson line and the terminal station of the Oklahoma Railway. * * * Mr. Shartel states that there is no connection between the new organization and the Oklahoma Railway company …”

No connection? Yeah, right. Shawnee interurban line? Yeah, right, Shawnee again (that never happened). According to Bender’s excellent article, “Contrary to the three-forked system [ed note: west, north & south], L.E. Patterson had illustrated the ideal interurban system for Oklahoma City in Sturm’s Magazine in 1909. Like a spoked wheel, the lines ran outward in all directions leading from a central hub.” The article also notes that neither the Oklahoma Railway Company nor the Patterson lines model well served the black section of Oklahoma City lying in the low lands to the southeast.

I could go on with this, but you’re probably bored silly even if you’ve gotten this far! So, with this, I’ll close this section, at least for now, on the early-day development and background of the Oklahoma City trolley system … the interurban system will be discussed in Trolleys Part 2.

EYE CANDY. In this section, a tour is made of early day trolleys and their tracks. Sometimes the locations are clear, sometimes not. But, all are within Oklahoma City. Except as otherwise noted for individual images, the pics below are from Whitstle Stop Trains’ excellent Oklahoma City Trolley CD which I heartily recommend to you. The store is located at 1313 West Britton Road in Oklahoma City.

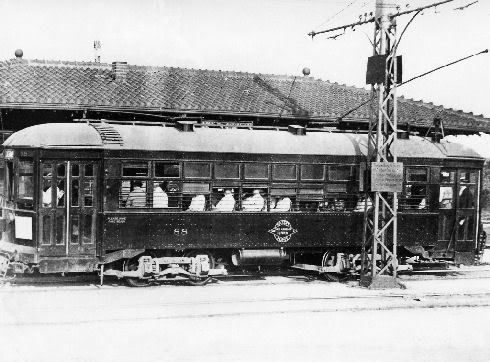

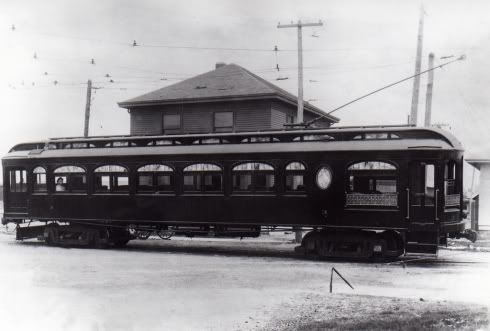

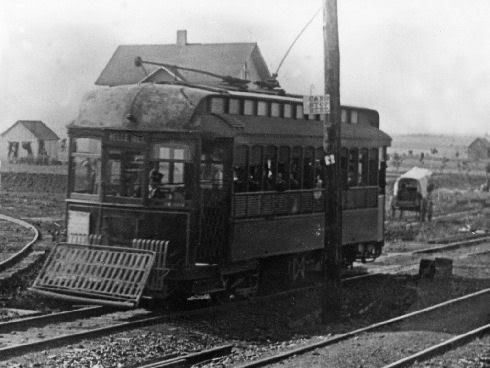

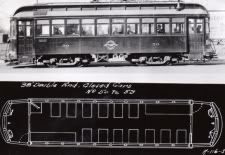

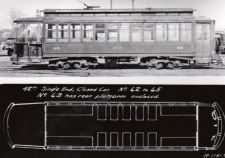

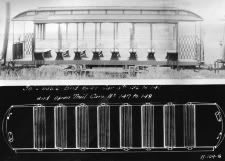

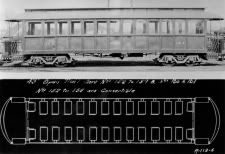

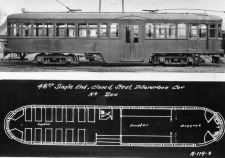

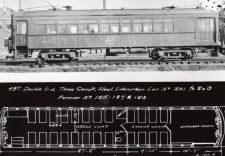

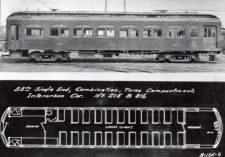

Early Car Types. Several existed as you see below. I’ve not included any of the freight or other non-passenger vehicles.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

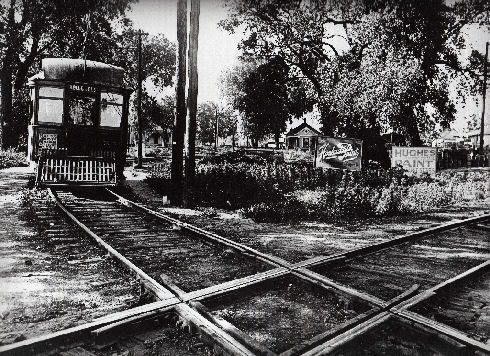

From Whistle Stop Trains

Here’s a “real” open air car

|

|

|

|

From Oklahoma County: Heart of the Promised Land

Around 1915, a car with a wicker chair lounge in the back

From Oklahoma County Metropolitan Library System

A closeup of the wicker chair lounge

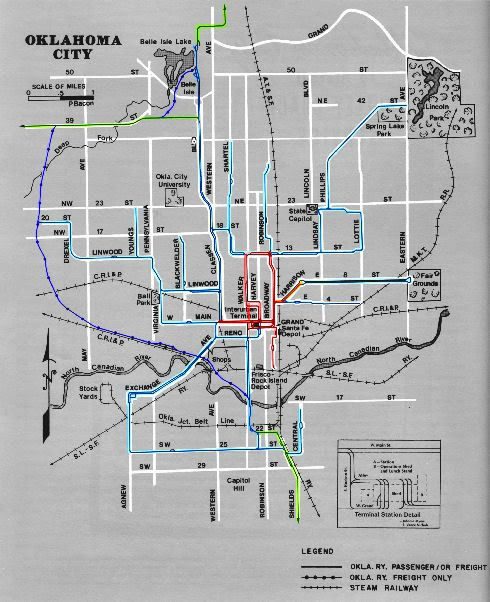

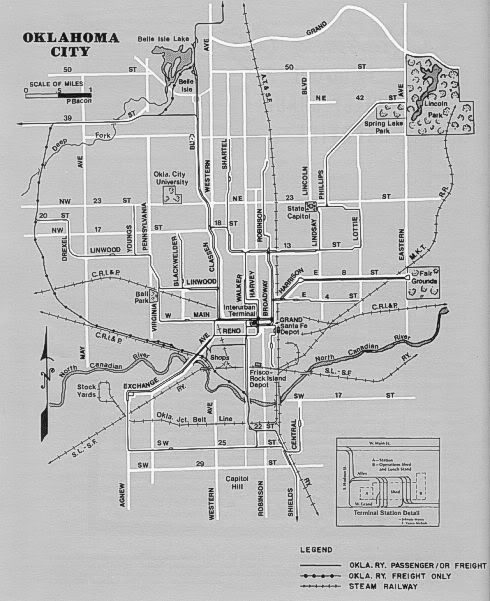

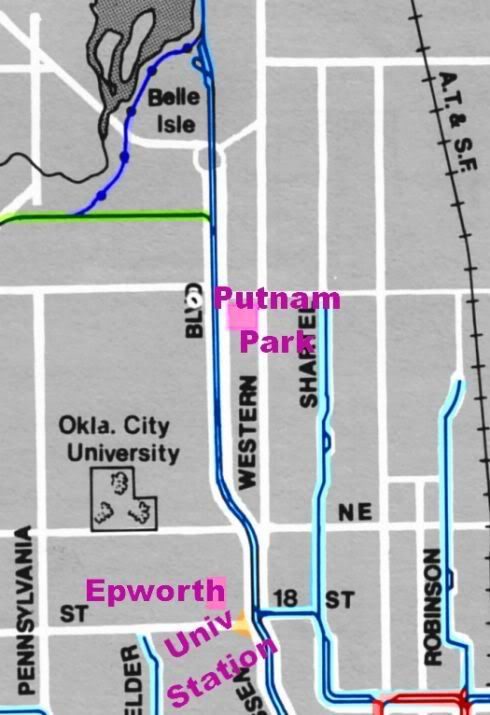

A Map Around Town. The map below is from When Oklahoma Took The Trolley … first, as it appears in the book, and, second, with the trolley and interurban lines color-coded. The map may come in handy when particular locations are referenced below.

The Color-Coded Version

Red=original tracks, Light Blue=later passenger or freight

Purple=freight only, Green=interurban

From Oklahoma County: Heart of the Promised Land

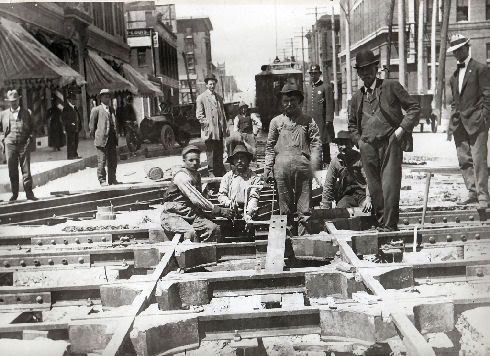

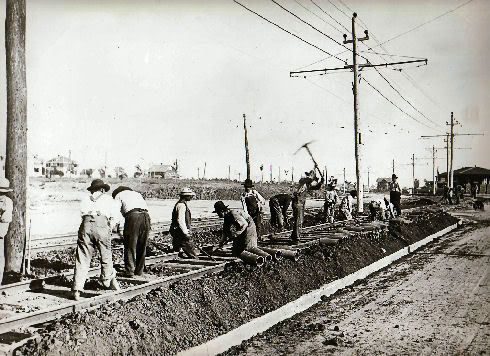

Laying Tracks Downtown

From Whistle Stop Trains (next 2 pics)

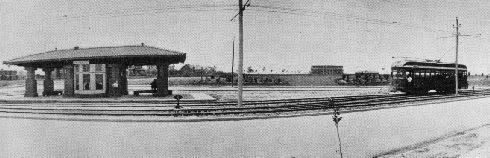

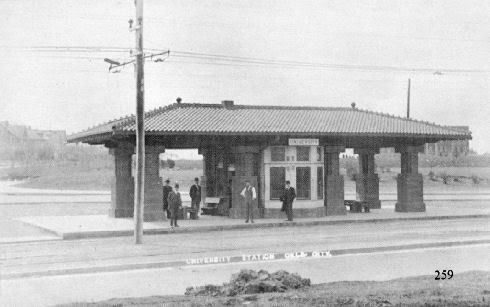

On Classen Approaching University Station

From Oklahoma County: Heart of the Promised Land

University Station just north of NW 17th & Classen

From Whistle Stop Trains

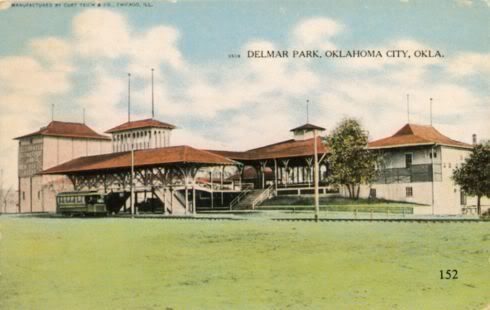

A Trolley In Maywood

From Vanished Splendor (I)

The Maywood Line apparently ran to Delmar Garden

From Metropolitan Library System

Open Air Car At Delmar (1909)

From Whistle Stop Trains

More Track Being Laid

(I can’t place the location … let me know if you do)

From Whistle Stop Trains

University Station Again

From Vanished Splendor II

Notice the building in the right background

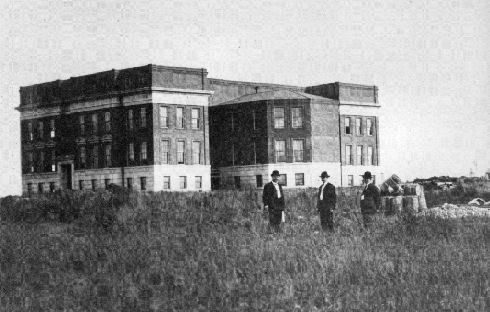

Epworth University. The building in the right background, above, is Epworth College or University, built in 1903, later named Oklahoma City University and, since 1922, located on NW 23rd. This development serves as an excellent example of “enlightened self interest.” The Methodist Episcopal Church (today, the “United Methodist Church”) had been divided by Civil War like so many other protestant denominations and, in this time, existed in two forms: the Methodist Episcopal Church headquartered in Shawnee, and the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, headquarterd in Chickasha. Anton Classen parlayed an arrangement which benefitted the churches coming together to form a common university, the city because it “got” the university, and Mr. Classen since it would be constructed along the trolley line which would go north on Classen Boulevard. Oklahoma City’s competition included Enid, Fort Worth, and Winfield, Kansas. Born Grown says that, “Adoption of the proposal by both [Methodist] conference groups was the first successful effort toward unity since seventeen years before the Civil War.” The Oklahoma City proposal, spearheaded by Classen, included the creation of a diagonal street from center city toward the proposed campus, a street which we now call “Classen Drive” — then it was just called “Classen” — which then had its northern terminus at NW 17th Street. The donation of land and gift of $100,000 capital won the day. So, when you hear about “University Addition,” that’s where the name comes from, as does “University Station” at NW 17th & (regular) Classen.

Epworth University Near University Station

Epworth University Today — Now Epworth United Methodist Church

University Station Marker, North of Braums

From Whistle Stop Trains

Early NE 6th & Walnut

From Whistle Stop Trains (next 4 pics)

In Capitol Hill

From Whistle Stop Trains

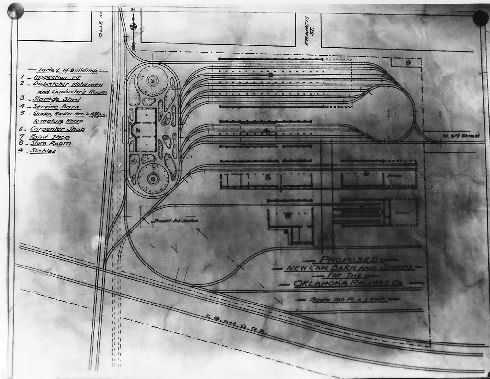

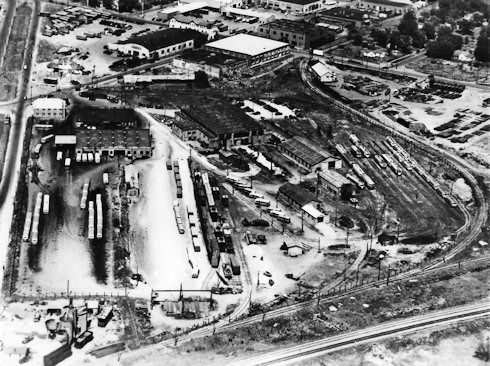

Car Barns & Facilities at NW 3rd & Ollie

Notice the Car Barn At The Right

From Oklahoma County: Heart of the Promised Land

From Vanished Splendor (I) (next 2 pics)

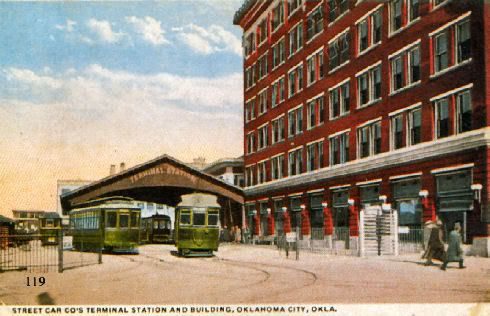

The Terminal Building (1910)

From Whistle Stop Trains

From Oklahoma County: Heart of the Promised Land

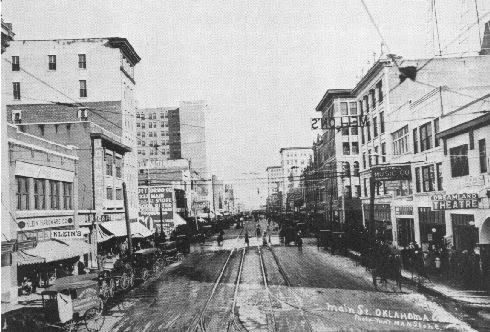

Main Street

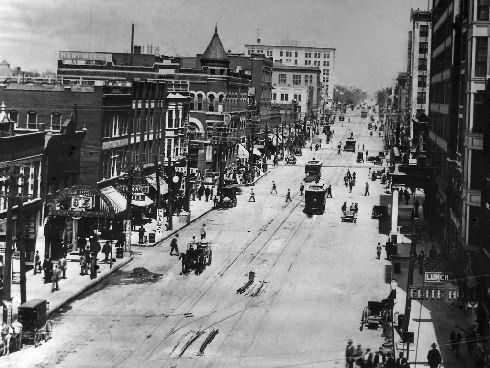

From Whistle Stop Trains (next 7 pics)

Broadway

In Front of Carnegie Library

By Lee-Huckins Hotel around 1910

(The Herskowitz Building in background was completed in 1910)

By the Patterson (left) and Levy (Mercantile) (right) Buildings

From Whistle Stop Trains (next 2 pics)

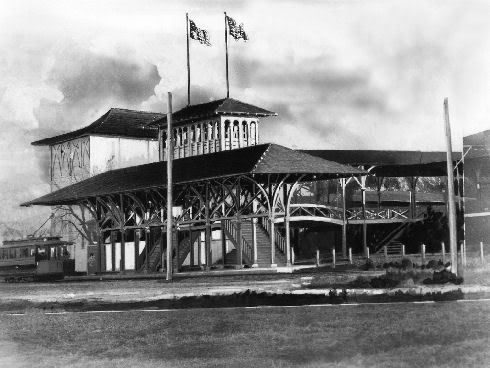

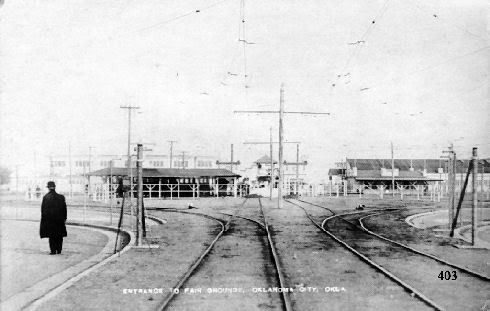

Fairgrounds Terminal, 1908 or 1909

Improved

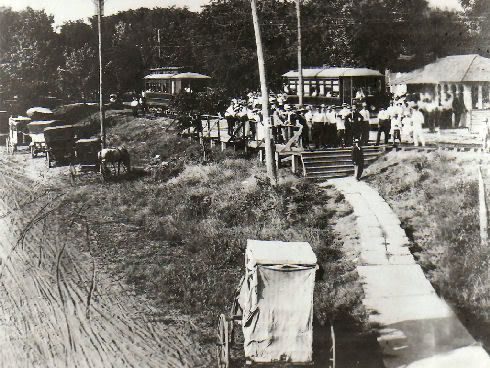

From VanishedSplendor II (next 2 pics)

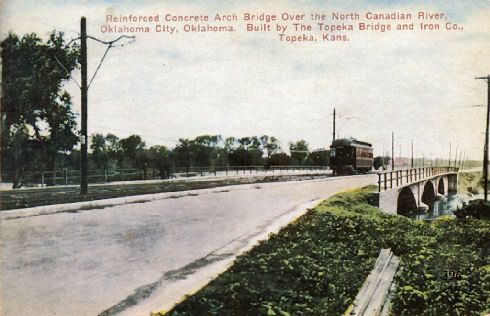

1st Exchange Avenue Bridge

Crossing North Canadian To Packingtown

From Whistle Stop Trains (next 7 pics)

National Hotel in Packingtown

The Stockyards

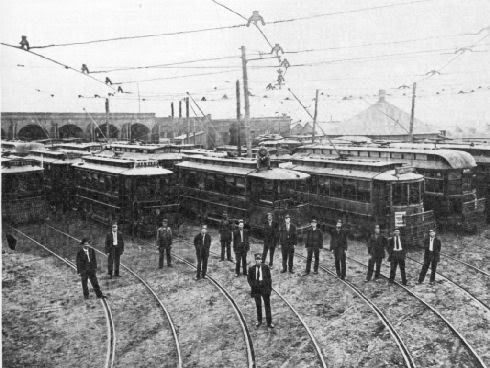

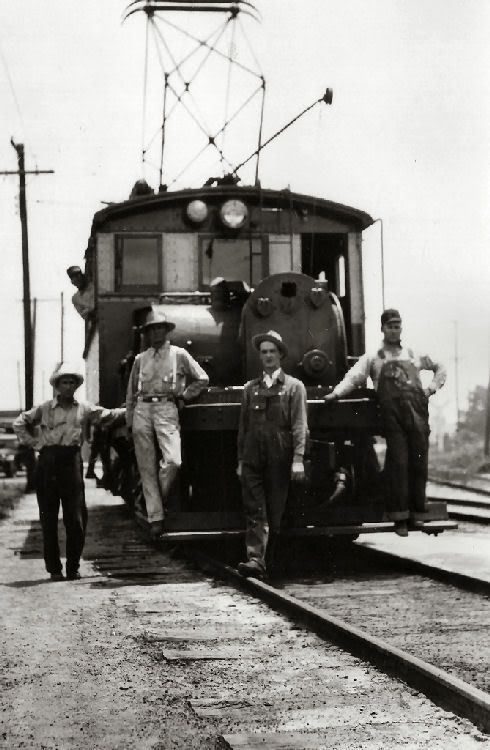

A Stockyards Crew

The Stockyards Office in Later Times

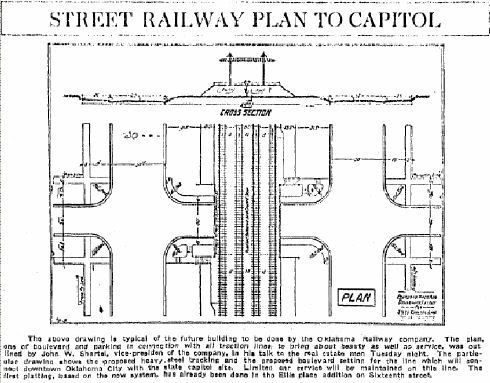

From the Oklahoman, September 22, 1910

Oklahoma Railway Company’s 1910 Plans for State Capitol (it never happened)

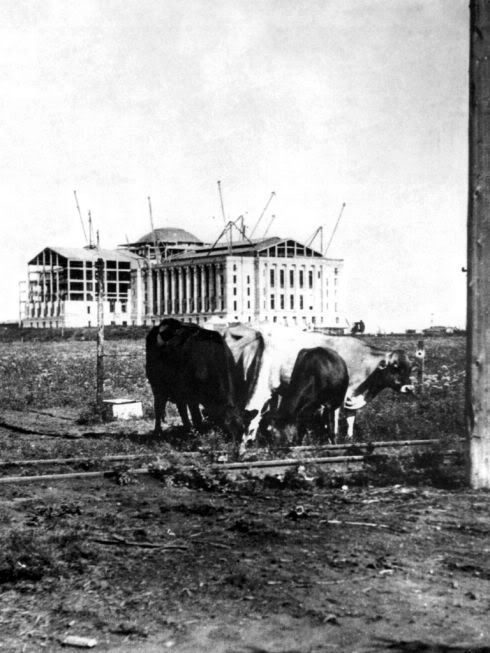

From Historic Photos of Oklahoma City

The Capitol in 1916 – Harn’s Line in Foreground

From Whistle Stop Trains

Back on Classen — New Construction

Cropped Map For Classen Perspective

(larger image not available)

From VanishedSplendor (I)

Putnam Park Around 1904-05 (The book says 1900, but

trolleys didn’t exist then … hence a likely date)

From VanishedSplendor II

Putnam Park Later Became Memorial

Memorial Park Today

Between Classen & Western, NW 36 & NW 34

From Oklahoma City: Statehood to 1930

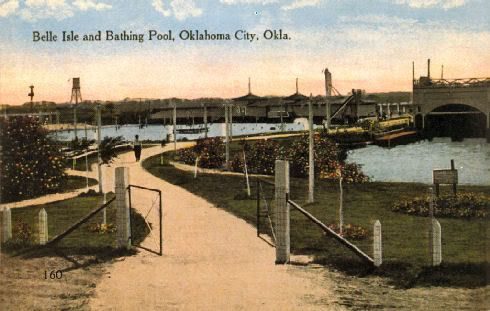

The Plan For Belle Isle Park

(Trolley line is near the top)

From Whistle Stop Trains

On Classen Looking South Toward NW 38th

(See the apartment house in the background)

The Apartment House Today — 1235 NW 38th

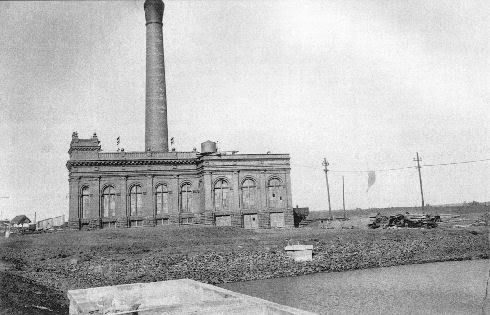

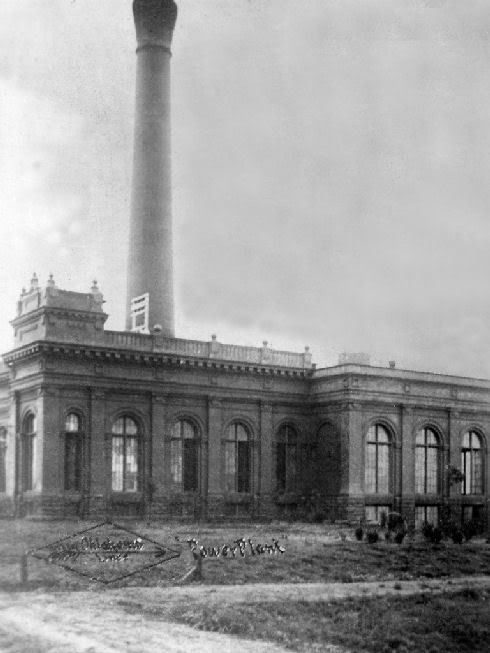

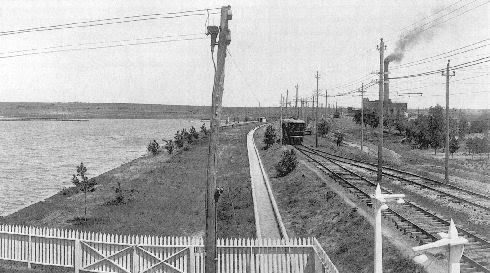

Belle Isle. Electricity was obviously needed to power the trolleys. However, during peak periods, the electric utility favored downtown lights and city use resulting in power to trolleys being suspended, the result being … stranded street cars and passengers! So, the ORC built its own power supply at Belle Isle Lake in 1908. Problem solved. Note: Oklahoma City: Statehood to 1930 says the plant was built in 1910, but Oklahoman articles show that it was commenced in 1907 and done in 1908.

From Whistle Stop Trains

Another View

From Vanished Spendor (I)

Why Not Build A Great Park Way Up There?

From Oklahoma City: Statehood to 1930

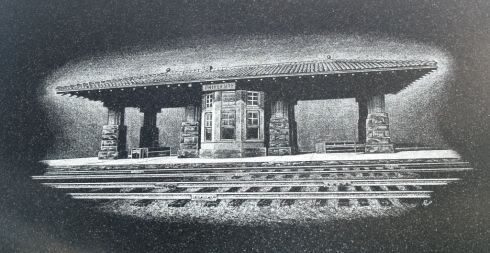

Trolley Docks at Belle Isle Park

From Oklahoma County Metropolitan Library System

Trolley Platform at Belle Isle

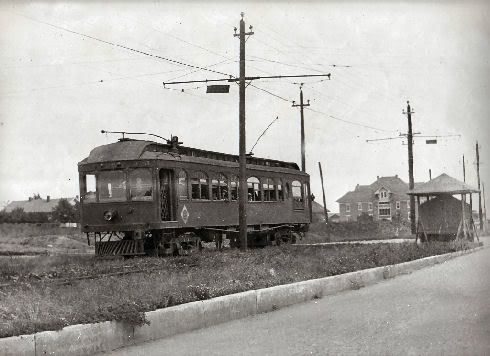

From Whistle Stop Trains

A Trolley Going To (From?) Belle Isle

I’ll end this section with a quotation from Roy Stewart’s Born Grown at page 164:

After Classen’s death in [December] 1922, Ed Overholser, president and manager of the Chamber of Commerce, who had been here since eight months after the opening, had this to say about Anton Classen: “It has been my good fortune to know intimately all the real town builders. Through association with my father I came in daily contact with them … I have been in their councils … I have heard them express their visions, hopes and fears … I have seen results of all these things crystalized into the wonderful city that we have … One man took a pencil and figured the area in square miles which this city must have to build upon, in the firm conviction that it would have 100,000 population. My father said that if he lived his alloted time he would see a city of 25,000. When that point was reached he raised the estimate to 40,000. I heard C.C. [C.J.?] Jones make the prediction that the figure would be 50,000 in his lifetime. Only Anton Classen believed 100,000 after studying the areas needed for residences and business, and other details. Then he began to purchase surrounding land that, in his judgment, the city would require. His success was due to the absolutely correct vision and working toward that vision.”

Oklahoma City’s population in 1920 was 91,295. Ten years later it reached 185,389. So, in the year he died, I’m figuring that he got it right on the nose! I’ll take a capitalist like Anton Classen any day, and I’m proud to be living in University Addition, a part of the Mesta Park Neighborhood, myself!

That’s all for now. Next stop: Okc Trolleys, Part II.

Go To Top

Go To Trains & Trolleys Intro Go To Trains, Part 1

Go To Trains Part 2 Go To Trains Part 3

Go To Trains Part 2A Go To Trolleys Part II