This article was originally posted on February 29, 2012, in very preliminary form and it has taken me until May 9 to finish it. It is VERY long (about 69 pages if you can print it without the left pane and top banner) but it is bookmarked so that you can move quickly to what you want to see. The largest section by far is a rather thorough account of the fascinating history of the Gold Dome, originally Citizens State Bank, which contains about 56 pages. Enjoy!

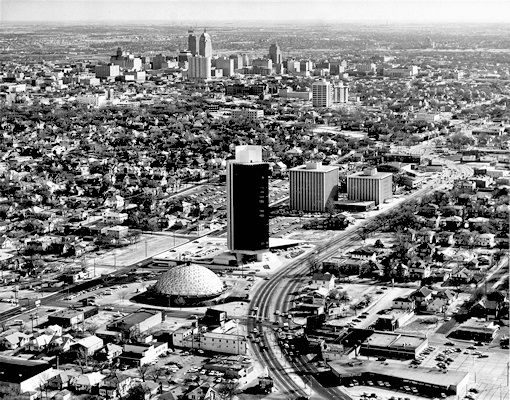

Click the above image for a 1024 px wide view

or click below for even larger views …

2000 px wide view 6040 px wide view

I rarely make a post based upon just a single photograph, but this is the exception that proves the rule — based upon the photo, I’ll write three articles, this being the first. A good friend and excellent Oklahoma City attorney, Jim Slayton, recently furnished me with a paper photo that he owns — one of his clients mailed it to him on February 24, 1967 — and the photo was probably taken in January or February 1967 or in late 1966 at the earliest. As you can see, the downtown skyline is in the background, a substantial part of Midtown is in the middle, and the Gold Dome and other properties along NW 23rd Street are in the foreground. The photo was taken from a vantage point slightly north of NW 23rd and Classen Boulevard and looks southeasterly toward downtown.

This is the first of three articles which takes a closer look at many of this photo’s pieces … organized by slices.

The Middle Slice — Midtown — This Will Come Next

The Bottom Slice — Uptown — This Is Presented Here

The remainder of this Part 1 article focuses upon the parts within the bottom slice above shown, with a good bit of history thrown in.

Click on any image for a larger view

| 1 — Beverly’s | 5 — Vacuum Cleaner Sup. | 9 — Cinema Mayflower |

| 2 — Battens Flowers | 6 — Oklahoma Blueprint | 10 — Beef & Bun Restaurant |

| 3 — Gold Bond Gifts | 7 — Townleys Milk Bottle | 11 — Someplace Else |

| 4 — Hammond Organ | 8 — Classen Cafeteria | 12 — Citizens State Bank |

Bottom Slice History & Additional Images. The 1967 photo certainly does not take in all of “Uptown” — it does not go eastbound much further than Western Avenue — but it nonetheless contains that part of Uptown which was centered around Classen and NW 23rd. Historical notes and images relevant to the bottom slice of this 1967 photo follow. For the most part, boldfaced names are the property occupants at the time the 1967 photo was taken.

Beverly’s Chicken In the Rough. I’m not able to document when this Beverly’s at 1220 NW 23rd came to exist — the earliest Oklahoman reference I’ve located is a February 27, 1966 want-ad for a waitress. But, Mo Moon (see the 1st comment at the end of this article) remembers it being there in 1962 or 1963. Note, also, that Mo recalls “the fresh-squeeze orange juice from those tall, green juicers, and the fact that the waitresses were all required to wear girdles beneath their neat white uniforms,” points worth remembering! In 1988, the same property became the home of Jeff’s Country Cafe but in 2004 it became the location of a Walgreen’s Pharmacy. Then, Jeff’s Country Cafe moved to its present location at 3401 N. Classen. For more, see discussion in the Citizens State Bank section, below.

Beverly’s Chicken In the Rough. I’m not able to document when this Beverly’s at 1220 NW 23rd came to exist — the earliest Oklahoman reference I’ve located is a February 27, 1966 want-ad for a waitress. But, Mo Moon (see the 1st comment at the end of this article) remembers it being there in 1962 or 1963. Note, also, that Mo recalls “the fresh-squeeze orange juice from those tall, green juicers, and the fact that the waitresses were all required to wear girdles beneath their neat white uniforms,” points worth remembering! In 1988, the same property became the home of Jeff’s Country Cafe but in 2004 it became the location of a Walgreen’s Pharmacy. Then, Jeff’s Country Cafe moved to its present location at 3401 N. Classen. For more, see discussion in the Citizens State Bank section, below.- Batten’s Flower & Gift Shop. This florist business was one of, if not the, oldest in the city when this 1967 photo was taken and was then owned by Roy E. Stephenson and his wife Sara Marie Stephenson, nee Batten. In 1921, the business was owned by Sara’s parents and its sole location was 320 or 322 W. Main (varying by Oklahoman ads) — see this 1924 Oklahoman ad as an example — but it expanded to include other locations, as well, including NW 23rd & Harvey in 1952. The location shown in this 1967 photo was built in 1956. Roy E. Stephenson died in December 1971 followed by his wife, Sara, in August 1982. The business continued to operate at the location, presumably by surviving family members, until at least until 1988, the last Oklahoman ad appearing in the Oklahoman on February 9, 1988. Today, the property is the home of Fashion Sports and Uniforms.

Gold Bond Gifts. This is the place where Gold Bond Stamp hoarders took their books of stamps to exchange them for goods, e.g., electric shavers and the like. IGA groceries were some of the more prominent retailers that used Gold Bond Stamps to encourage shopping — Central National Bank did so, as well.

Gold Bond Gifts. This is the place where Gold Bond Stamp hoarders took their books of stamps to exchange them for goods, e.g., electric shavers and the like. IGA groceries were some of the more prominent retailers that used Gold Bond Stamps to encourage shopping — Central National Bank did so, as well. Hammond Organ Studios of Oklahoma City. Until sometime in the mid-1950s, this property was residential. Its first commercial use appears to have been a Blalock Oil gas station, that venture being purchased by Kerr McGee in 1955. Before 1961, it became Lee Devin TV, but it became Hammond Organ Studios of Oklahoma City with an August 1, 1961, grand opening and that business lasted at least through 1975. By 1979, the premises became Audio Associates. Today, this property is part of the Jade Asian Plaza. County Assessor records reflect that this small shopping center was built in 1972, but it is evident from the 1967 photo that it was built several years earlier. Today, the strip shopping center which contains both #3 and #4 is known as the Jade Asian Plaza, shown below on March 1, 2012.

Hammond Organ Studios of Oklahoma City. Until sometime in the mid-1950s, this property was residential. Its first commercial use appears to have been a Blalock Oil gas station, that venture being purchased by Kerr McGee in 1955. Before 1961, it became Lee Devin TV, but it became Hammond Organ Studios of Oklahoma City with an August 1, 1961, grand opening and that business lasted at least through 1975. By 1979, the premises became Audio Associates. Today, this property is part of the Jade Asian Plaza. County Assessor records reflect that this small shopping center was built in 1972, but it is evident from the 1967 photo that it was built several years earlier. Today, the strip shopping center which contains both #3 and #4 is known as the Jade Asian Plaza, shown below on March 1, 2012.

Vacuum Cleaner Supply. If you’re like me, you think of this business located at 2405-2407 Classen as “Hoovers Vacuum” since that name is and has been prominently displayed and even though the business name for this mom and pop vacuum service center was and is “Vacuum Cleaner Supply.”

Vacuum Cleaner Supply. If you’re like me, you think of this business located at 2405-2407 Classen as “Hoovers Vacuum” since that name is and has been prominently displayed and even though the business name for this mom and pop vacuum service center was and is “Vacuum Cleaner Supply.”

The first Oklahoman ad I located for this business was May 5, 1960, shown here at 2407 Classen. The building abutting 2407 to the south was 2405 Classen until the buildings were joined to form a single property. Current County Assessor records show that Winfred and Velma Parker own the properties and that they also own property #6, below.

The first Oklahoman ad I located for this business was May 5, 1960, shown here at 2407 Classen. The building abutting 2407 to the south was 2405 Classen until the buildings were joined to form a single property. Current County Assessor records show that Winfred and Velma Parker own the properties and that they also own property #6, below.

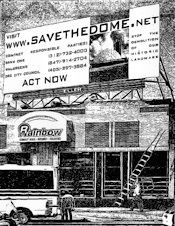

The Hoover shop is presently boarded up and appears to have ceased operations, even though its vacuums and parts thereof are readily viewable from the sidewalk in its overflow storage location in the former Rainbow Records to the south. See Oklahoma Blue Print below. County Assessor records show the property was constructed in 1914. Oklahoman want ads show that 2405 Classen was used for various purposes — in 1959 it was the campaign headquarters of Ralph M. Cissne, Ward 1 election candidate; from 1960 through 1963, it was Tom Ford Company, a carpet and furniture seller. Oklahoma Blue Print & Supply Co. Although I’m showing the County Assessor’s 2005 photo of Rainbow Records here (since that’s probably what most of us remember for this location), this property at 2401 Classen was Oklahoma Blue Print & Supply Co. when the 1967 photo was taken. County Assessor records show present ownership of the property are the same Parkers identified in #5, above, that it was constructed in 1914, and that the building was very oddly shaped. Earlier Oklahoman ads and articles show that the property was a Klein Oil Co. service station in 1925, Southern Meats & Groceries in 1930, Roberts Drug Co. between 1946 and March 1964, a Mobil Service Station in November 1964, and then Oklahoma Blue Print & Supply Co. in October 1965 until at least January 1969. In 1975, the location became Rainbow Records, once said to be “Oklahoma’s oldest independent record store,” and that is how most of us remember the property. Rainbow Records moved to 3709 N. Western in March 2004.

Oklahoma Blue Print & Supply Co. Although I’m showing the County Assessor’s 2005 photo of Rainbow Records here (since that’s probably what most of us remember for this location), this property at 2401 Classen was Oklahoma Blue Print & Supply Co. when the 1967 photo was taken. County Assessor records show present ownership of the property are the same Parkers identified in #5, above, that it was constructed in 1914, and that the building was very oddly shaped. Earlier Oklahoman ads and articles show that the property was a Klein Oil Co. service station in 1925, Southern Meats & Groceries in 1930, Roberts Drug Co. between 1946 and March 1964, a Mobil Service Station in November 1964, and then Oklahoma Blue Print & Supply Co. in October 1965 until at least January 1969. In 1975, the location became Rainbow Records, once said to be “Oklahoma’s oldest independent record store,” and that is how most of us remember the property. Rainbow Records moved to 3709 N. Western in March 2004.

Today, the property seems to be the overflow location of lots of used vacuum cleaners, parts, and other stuff by the building’s present owners. The photos below were taken on March 1, 2012, looking through the windows of the former Rainbow Records premises. JenX has blogged about this and I am compelled to agree with her, even though I lean to giving the benefit of the doubt to local mom and pop stores. Probably, nothing can be done as long as the owners follow city code requirements. But, someday, perhaps the owners may come to have a sense of civic pride. Or not. Also, see this part of #12, Citizens State Bank, below.

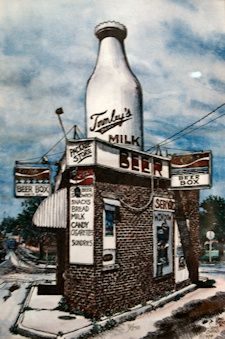

Townley’s Milk Bottle. The very large white milk bottle was placed on top of the very small flatiron building building at 2426 N. Classen in 1948. The small flatiron 1920 building is listed on the National Historical Register of Historic Places, something which would not likely have happened but for the bottle.

Townley’s Milk Bottle. The very large white milk bottle was placed on top of the very small flatiron building building at 2426 N. Classen in 1948. The small flatiron 1920 building is listed on the National Historical Register of Historic Places, something which would not likely have happened but for the bottle.

The County Assessor’s drawing shows the building’s floorspace at only 392 square feet, and it’s hard to imagine that a tenant could pull off a successful business there.

The County Assessor’s drawing shows the building’s floorspace at only 392 square feet, and it’s hard to imagine that a tenant could pull off a successful business there.

But, as part of today’s Oklahoma City Asian District, the present day Saigon Baguette has managed to pull that off that improbability. This photo was taken on March 1, 2012.

But, as part of today’s Oklahoma City Asian District, the present day Saigon Baguette has managed to pull that off that improbability. This photo was taken on March 1, 2012.

However, before Braum’s, there was Townley’s, the bottle in place when the 1967 photo was taken and the milk bottle that older folk identify with. Oklahoma City renowned artist Greg Burns shows the Townley’s milk bottle which made it an Oklahoma City icon.

However, before Braum’s, there was Townley’s, the bottle in place when the 1967 photo was taken and the milk bottle that older folk identify with. Oklahoma City renowned artist Greg Burns shows the Townley’s milk bottle which made it an Oklahoma City icon.But what were the origins of this small tract, building, and milk bottle? Brandon Bowman writes this here:

The unusual shape of the property was created by the diagonal meeting of the old Belle Isle streetcar line with northwest 23rd Street. The resulting triangular lot was chosen as the construction site for a similarly shaped building, which was completed in 1930. Originally known as “Triangle Grocery and Market”, the building was a stop on the streetcar line until the rail service was stopped in 1947, and the tracks were paved for roads. Despite no longer being a way point for mass transit, the little triangle building and site remained prime commercial territory, a small island in a sea of traffic.

The name of the building was changed to “Milk Bottle Grocery” shortly after a large metal milk bottle sign was added to the roof in 1948. With the lack of adjacent ground space for a sign, the only space left available for a sign was the roof. To be effective, the sign had to be sufficiently eye-catching to gain the attention of passing traffic, and the result was a metal sign almost as tall as the building itself. The sign, being 8 feet wide and almost 11 feet tall, almost dwarfs the building that serves as its base. It’s constructed of sheet metal, and has a tapered neck, rimmed mount, and crenelated cap, just like the old glass milk bottles of the early 20th century. The sign was traditionally rented separately from the building below, and was used to advertise local dairies. Over the years, the sign has advertised Steffen’s Dairy, Townley’s Dairy, and nowadays carries the Braum’s emblem.Bowman’s observations are completely consistent with the registry application filed with the with National Register of Historical Places, and that’s good enough for me and there you have it.

Classen Cafeteria. This property was located at 2400 N. Classen (most often called 2400 Classen) Boulevard and, when the principal photo was taken in December 1966 or January 1967, it was Classen Cafeteria (observable by clicking on the thumbnail shown here), the entry being from Classen Boulevard. The earliest Oklahoman mention I could find for the address is a 1940 ad showing that it was a Humpty-Dumpty grocery. In the mid-1940s O’Mealey’s Cafeteria opened their first business in the property. Vanished Splendor II by Jim Edwards and Hal Ottaway (Abalache Book Shop Publishing 1983) says that Classen Cafeteria began its operations at the address in mid-1948 and the Oklahoman’s first mention was in February 1948.

Classen Cafeteria. This property was located at 2400 N. Classen (most often called 2400 Classen) Boulevard and, when the principal photo was taken in December 1966 or January 1967, it was Classen Cafeteria (observable by clicking on the thumbnail shown here), the entry being from Classen Boulevard. The earliest Oklahoman mention I could find for the address is a 1940 ad showing that it was a Humpty-Dumpty grocery. In the mid-1940s O’Mealey’s Cafeteria opened their first business in the property. Vanished Splendor II by Jim Edwards and Hal Ottaway (Abalache Book Shop Publishing 1983) says that Classen Cafeteria began its operations at the address in mid-1948 and the Oklahoman’s first mention was in February 1948.

This image is is a postcard from Vanished Spendor II. The book’s text says that Classen Cafeteria closed “sometime in 1967.” Later tenants were Jeans America (1972), The Jeannery (1972), Oklahoma Rehab, Inc. (at least by 1993 and into 1994). In 1996 a $500,000 building permit was issued to Anderson & House to construct a retail store, and, presumably but I’m not certain, this project involved the destruction of the building shown in the 1967 photo. In any event, the property became part of the parking lot for an Eckerd Drug, and, later, the CVS Pharmacy at 2412 N. Classen which occupies the space today.

This image is is a postcard from Vanished Spendor II. The book’s text says that Classen Cafeteria closed “sometime in 1967.” Later tenants were Jeans America (1972), The Jeannery (1972), Oklahoma Rehab, Inc. (at least by 1993 and into 1994). In 1996 a $500,000 building permit was issued to Anderson & House to construct a retail store, and, presumably but I’m not certain, this project involved the destruction of the building shown in the 1967 photo. In any event, the property became part of the parking lot for an Eckerd Drug, and, later, the CVS Pharmacy at 2412 N. Classen which occupies the space today. Cinema Mayflower. Independent suburban theater owner Sam Caporal’s Mayflower Theater at 1133 NW 23rd Street opened in April 1938 with the 1936 movie Pennies From Heaven staring Bing Crosby and featuring Louis Armstrong in a supporting role, a rare happening in that day. Click here for the Oklahoman’s movie ad.

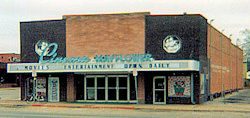

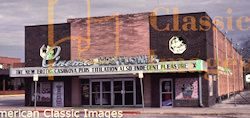

Cinema Mayflower. Independent suburban theater owner Sam Caporal’s Mayflower Theater at 1133 NW 23rd Street opened in April 1938 with the 1936 movie Pennies From Heaven staring Bing Crosby and featuring Louis Armstrong in a supporting role, a rare happening in that day. Click here for the Oklahoman’s movie ad.

This wasn’t Caporal’s first suburban movie venture, he having established the Yale Theater in Capitol Hill at least as early as 1921 according to William D. Welge’s Oklahoma City Remembered (Arcadia Publishing 2007). Caporal later built and operated the Bison (1941 – 1314 NE 23rd) and Skyview Drive-In (1948 – 3800 NE 23rd).

This wasn’t Caporal’s first suburban movie venture, he having established the Yale Theater in Capitol Hill at least as early as 1921 according to William D. Welge’s Oklahoma City Remembered (Arcadia Publishing 2007). Caporal later built and operated the Bison (1941 – 1314 NE 23rd) and Skyview Drive-In (1948 – 3800 NE 23rd).As best as I can determine, the theater rarely if ever showed first run movies but in the main they were good solid movies, often double or triple features. In 1966 the Mayflower Theater closed temporarily to be completely remodeled and reopen in October as the Cinema Mayflower, the original intent being to present quality foreign films. That idea eventually failing, in its last years, the theater resorted to X-rated films which perhaps catered to a daytime male business-worker group — such as might occur for an extended lunch-and-a-movie break (yeah, I’ve been there and done that).

1975 – Credit Jeff Chapman

1985 – Credit American Classic

After the movie theater closed around 1991, comments here say that the property operated as “Planet Earth” for a time as a live music venue. The property was purchased in 1996 by Vietnamese refugee immigrants Johnny and Tina Hy who opened Asian Restaurant, and, today, it is part of Sun Moon Plaza. A March 2012 photo of the former Mayflower is shown below.

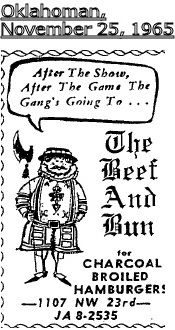

Beef & Bun Restaurant. That was the name of the business property at 1107 NW 23rd Street in 1967 when the aerial photo was taken. In 1944 the residential property which then occupied the space was either destroyed or removed and from 1947 through 1963 the Carnation Company operated a business at the property, it frequently advertising in the Oklahoman for fountain help and waitresses during that 16-year period. See the Carnation Ice Cream Store article in Steve Lackmeyer’s Oklahoma City history website for much more about that store, including photos.

Beef & Bun Restaurant. That was the name of the business property at 1107 NW 23rd Street in 1967 when the aerial photo was taken. In 1944 the residential property which then occupied the space was either destroyed or removed and from 1947 through 1963 the Carnation Company operated a business at the property, it frequently advertising in the Oklahoman for fountain help and waitresses during that 16-year period. See the Carnation Ice Cream Store article in Steve Lackmeyer’s Oklahoma City history website for much more about that store, including photos.

For a time, the property experienced an ethnic identity crisis. From 1965 through 1972, it was the Beef & Bun but for a short time in 1974 it was the home of “Happy Days,” a Jack Sussy Italian restaurant. By 1979 until 1981, it was the home of R. L. Sullivan’s Steak & Spaghetti restaurant and in 1982 it was renovated to become the home of New Orleans and southern cooking as Rhett’s Place, but that only lasted until 1983. In July 1983, the property was renovated and became the home of “the 23 Corner” restaurant operated by Loc & Kim Le. Loc, a political refugee from Vietnam after the fall of Saigon in 1975, was one of the many Vietnamese who came to call Oklahoma City home. But, other than egg rolls, Asian food was apparently not on the menu. When 23 Corner opened, Loc and Kim already owned and operated two Jimmy’s Egg restaurants in the city and American food was the principal offering at 23 Corner, including the same omelets served at their Jimmy’s Eggs in addition to steaks, hamburgers, and seafood dishes. I’ve not determined when 23 Corner stopped operating but Loc and his family has continued the expansion of Jimmy’s Egg with other franchises in and beyond the city.

For a time, the property experienced an ethnic identity crisis. From 1965 through 1972, it was the Beef & Bun but for a short time in 1974 it was the home of “Happy Days,” a Jack Sussy Italian restaurant. By 1979 until 1981, it was the home of R. L. Sullivan’s Steak & Spaghetti restaurant and in 1982 it was renovated to become the home of New Orleans and southern cooking as Rhett’s Place, but that only lasted until 1983. In July 1983, the property was renovated and became the home of “the 23 Corner” restaurant operated by Loc & Kim Le. Loc, a political refugee from Vietnam after the fall of Saigon in 1975, was one of the many Vietnamese who came to call Oklahoma City home. But, other than egg rolls, Asian food was apparently not on the menu. When 23 Corner opened, Loc and Kim already owned and operated two Jimmy’s Egg restaurants in the city and American food was the principal offering at 23 Corner, including the same omelets served at their Jimmy’s Eggs in addition to steaks, hamburgers, and seafood dishes. I’ve not determined when 23 Corner stopped operating but Loc and his family has continued the expansion of Jimmy’s Egg with other franchises in and beyond the city.  By July 1985 the property became the home of Shalimar India restaurant which appears to have operated at the location until 1987. In fact, I got my first taste of India-Indian cuisine there and loved it.

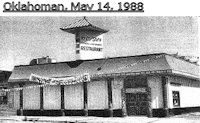

By July 1985 the property became the home of Shalimar India restaurant which appears to have operated at the location until 1987. In fact, I got my first taste of India-Indian cuisine there and loved it. In May 1988, the property was again remodeled and this time it became Kim Son, its owner Phung Hy serving Chinese, Vietnamese, Cantonese and other Asian foods. This restaurant lasted until 1995 or 1996 — the only Oklahoman evidence during that time being reports of a murder which occurred in November 1995 in the kitchen over a dispute concerning the victim’s wife’s fidelity. Both the victim and the accused, who plead guilty to manslaughter in May 1996, had the same last name. The Oklahoman report of the conviction was the paper’s last mention of Kim Son. By the time the 1996 photo below was taken, the property was called China Garden.

In May 1988, the property was again remodeled and this time it became Kim Son, its owner Phung Hy serving Chinese, Vietnamese, Cantonese and other Asian foods. This restaurant lasted until 1995 or 1996 — the only Oklahoman evidence during that time being reports of a murder which occurred in November 1995 in the kitchen over a dispute concerning the victim’s wife’s fidelity. Both the victim and the accused, who plead guilty to manslaughter in May 1996, had the same last name. The Oklahoman report of the conviction was the paper’s last mention of Kim Son. By the time the 1996 photo below was taken, the property was called China Garden. In 2004, the property was purchased by Asian Plaza, Inc., and Steve Lackmeyer reported in the July 26, 2006, Oklahoman that Mike Nguyen and Denny Ha, they having purchased this and other adjoining properties, had big plans to create a new “gateway” into Oklahoma City’s Asian District called “Sun Moon Plaza.” Although the recent recession appears to have put that project on hold, by the time this article is written it is fully underway. In the March 1, 2012, photo below, the property’s location would be to the left of the leftmost building shown in the photo.

In 2004, the property was purchased by Asian Plaza, Inc., and Steve Lackmeyer reported in the July 26, 2006, Oklahoman that Mike Nguyen and Denny Ha, they having purchased this and other adjoining properties, had big plans to create a new “gateway” into Oklahoma City’s Asian District called “Sun Moon Plaza.” Although the recent recession appears to have put that project on hold, by the time this article is written it is fully underway. In the March 1, 2012, photo below, the property’s location would be to the left of the leftmost building shown in the photo.Sun Moon Plaza  Someplace Else Deli & Bakery and Cookies Tavern. Unfortunately, the 1967 aerial photo of this property immediately east of the Gold Dome is not sufficiently crisp to be able read any signage on either of these buildings. The signage on the property at 2310 N. Western, Someplace Else today, appears to begin with “25,” but that’s far from certain, and the property located at 2304 N. Western, Cookies tavern today, is even less helpful in the 1967 aerial. The only thing certain is that neither property bore their present day names, shown below on March 1, 2012.

Someplace Else Deli & Bakery and Cookies Tavern. Unfortunately, the 1967 aerial photo of this property immediately east of the Gold Dome is not sufficiently crisp to be able read any signage on either of these buildings. The signage on the property at 2310 N. Western, Someplace Else today, appears to begin with “25,” but that’s far from certain, and the property located at 2304 N. Western, Cookies tavern today, is even less helpful in the 1967 aerial. The only thing certain is that neither property bore their present day names, shown below on March 1, 2012.

That said, here’s a bit of each property’s prior history. County Assessor records state that each property was constructed in 1935. The Someplace Else business has existed since 1976 but I don’t know when Cookies tavern was born but it was by 2001. Today, both properties have the same owners, David and Peggy Carty, the operators of the deli.2310 N. Western. Among other uses and names, this property was a small grocery and meat market (1947), Moser’s Pet Shop (1952-53), Universal Improvement Co. (1955), appliance repair (1959-60), DeSpain Realty (1962), Doll Haven & Hospital (1963-64), Acme Vacuum Sales (1964-65), AAA Upholstery (1968), and, most notably, Sound Warehouse (1972-1973), which I understand was that company’s first location.

2304 N. Western. In 1947, this property was advertised for rent as a storeroom, it measuring only 20 x 40 feet, with a glass front. In 1947, Robert Goodman’s beer license was revoked (the property being immediately east of Jefferson School — see Citizens State Bank, below) but that decision was appealed — the Oklahoman does not report the outcome but the appeal likely lost since Jefferson did not cease operating as a school until May 1950. Oklahoman ads between 1948 and 1985 do show the property’s names as Emerald Lounge (1948), Embro Lounge (1953), Ralph’s Club (1985). By November 2001, the premises were advertised as “Cookies.”

About the above pair of properties, Jim Kyle, a contributor here and former Oklahoman reporter, adds a bit more via his comment here on March 14:

Someplace Else was established in 1976. Peggy was a co-worker of my wife’s at the Crum & Forster Insurance Company’s claims office in the American Fidelity complex, and I remember the going-away party they had when she and David opened the deli. We still visit there often; David’s baked goods (made on the premises) are the best available!

When Cookie’s was operating as the Emerald Lounge, its owner also ran stock car races at a small track located on N. May avenue, near the present location of the Honeybaked Ham place. The track circled a small farm pond, and even ran over its dam. I used to shoot photos at the track on Sunday afternoons; he paid the winners at the lounge every Sunday night, so I would process the photos in a hurry and have 8 x 10s available for the winners to buy with their winnings that night! Thanks for bringing back those memories…You are more than welcome, Jim, but mainly, thanks to you for the additional memories about this fine pair of properties which would otherwise have been unknown!

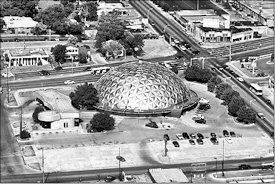

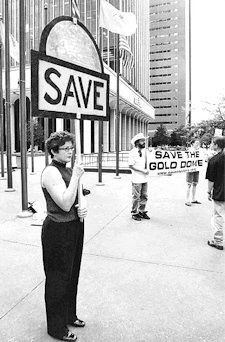

Citizens State Bank aka the Gold Dome. I’ve saved the best for the last in this bottom slice of the 1967 aerial photo, and it will take longer to tell the story than any of the above have. Constructed only about 9 years before the 1967 photo, this story not only involves the building structure and good times, it involves bank failure and the corruption of an eventual principal owner, but, in the end, the building’s salvation and redemption which was spearheaded by citizens concerned with the building’s preservation.

Citizens State Bank aka the Gold Dome. I’ve saved the best for the last in this bottom slice of the 1967 aerial photo, and it will take longer to tell the story than any of the above have. Constructed only about 9 years before the 1967 photo, this story not only involves the building structure and good times, it involves bank failure and the corruption of an eventual principal owner, but, in the end, the building’s salvation and redemption which was spearheaded by citizens concerned with the building’s preservation.

Glory Days Masked & Dark Days Corruption Bazarian

Mitchell Charges Mitchell Trial Appeal Mitchell Aftermath

Later Banks Salvation Restoration

● Origins — Jefferson Elementary School. Way before the Gold Dome was the 1905 Jefferson School which sat between Classen and Western along NW 23rd Street. I’ve not located any good images of the school, so the September 24, 1916, Oklahoman image will have to do for now.

The school was built in 1905 to serve the then far northwest part of the city, but as early as December 1905 it was seen as being too small to serve the city’s expanding northwest and in October 1907 four additional rooms were ready for use. Between these two dates, overall city student attendance grew by more than 1,000 students — 4,600 in December 1905 to 5,700 in October 1907.

I didn’t make a thorough study of the Oklahoman’s archives concerning the school, but this September 20, 1916, article did catch my fancy:

“Statue Bell” Is New Feature Introduced at Jefferson School — The “statue bell,” inaugurated at the Jefferson school by Principal G.B. Mitchell, is an innovation in the school signals in Oklahoma City. Four times a day — just before school starts in the morning and for the afternoon session, and at the close of each recess, the bell is sounded. Its ringing is a signal for every child to drop everything and become absolutely motionless. The pose lasts for sixty seconds.

The purpose of this bell is not only to teach the child the habit of instant obedience but also to prepare him to march into his classroom with a minimum of commotion.

The new bell has been used at the Jefferson school for about a week and it is proving to be decidedly successful, Mr. Mitchell said. [Emphasis supplied.]

Holy Human Midget Statues, Batman — principal Mitchell’s grade school kids must have been hell on wheels back in 1916 to merit them being turned into stone four times a day — or maybe it was only Mitchell who was the devil. I am reminded of Pink Floyd’s classic 1979 rock opera, The Wall … “Wrong! Do it again!” … “If you don’t eat yer meat, you can’t have any pudding! How can you have any pudding if you don’t eat yer meat?!”, and “You! Yes! You behind the bikesheds! Stand still, laddie!” One can but wonder if the good principal himself tried being a 60-second statue four times a day, Monday through Friday, or ever. “All in all it’s just another brick in the wall,” I’m thinkin’.

Skipping forward, the school board closed Jefferson School in May 1950 over heated objections by parents. Between the closing through 1954 or so the building was used as part of the school systems administrative offices and for other purposes. In September 1954 some if not all of the property was zoned for commercial use by the city council, over the objection of the city planning department, and the school board wanted to sell the property for commercial use, as well. In February 1956, attorneys David Shapard and Woodrow McConnell and insurance agency owner Hill Hodges signed a 120-day $410,000 option agreement to acquire the property and create an “ultra modern” 16-story on the property but the prospective purchasers failed to exercise their option. Finally, the September 5, 1956, Oklahoman reported that Citizens State Bank had agreed to purchase the property for $351,000 for its new location, although the agreement was contingent of full payment by February 1957. The last $150,000 payment was made on February 1 or 2, 1957, and the stage was set for Citizens State Bank to build its new building.

● Citizens State Bank. Citizens State Bank organized in December 1946, incorporators being C.R. Anthony, Fred Sewell, Felix Simmons, B.D. Eddie, V.V. Harris, and Virgil Brown, and its initial facility at 601 NW 23, on the northwest corner of Dewey and NW 23rd, opened for business on May 27, 1948. Even though presently vacant, the property still stands as shown by this photo taken in March 2012. The images below show the bank shortly after its construction and a few years later after adding a drive-through to the west. Both are from the Oklahoma Historical Society archives.

● Citizens State Bank. Citizens State Bank organized in December 1946, incorporators being C.R. Anthony, Fred Sewell, Felix Simmons, B.D. Eddie, V.V. Harris, and Virgil Brown, and its initial facility at 601 NW 23, on the northwest corner of Dewey and NW 23rd, opened for business on May 27, 1948. Even though presently vacant, the property still stands as shown by this photo taken in March 2012. The images below show the bank shortly after its construction and a few years later after adding a drive-through to the west. Both are from the Oklahoma Historical Society archives.

|

|

Advertising itself as a convenient suburban bank but with all of the facets of a downtown bank, the state bank grew rapidly and outgrew its original home and in only eight years, by September 1956, total deposits reached $20 million and it was the largest “state” bank in the state and the 9th largest of any bank in Oklahoma.

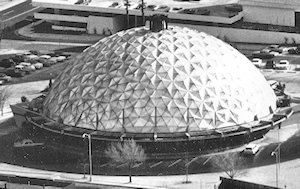

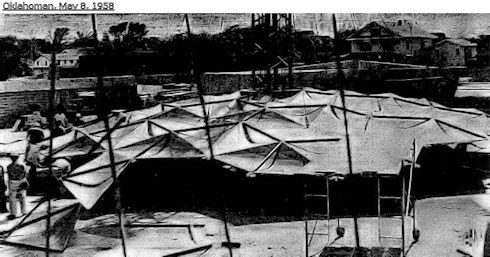

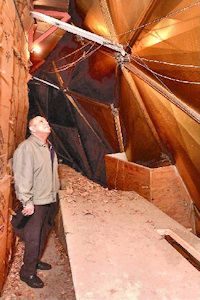

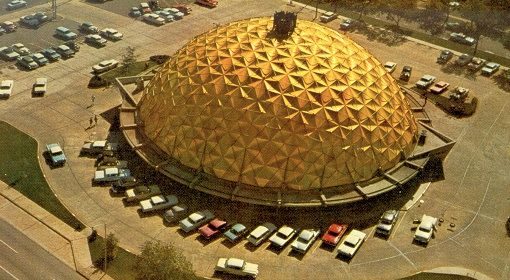

● The Gold Dome Is Born. When the bank purchased the old Jefferson School property for its new location in 1957, the remarkable design of its new facility wasn’t publicly known. After razing the school, bids were solicited for the project in November 1957, but if the Oklahoman contained any description of the property before May 1958 I couldn’t find it. It may well be that the public’s first knowledge was in the newspaper’s May 8, 1958, story and construction photo, the photo appearing below. Those passing by the Classen & NW 23rd intersection must have been puzzled and fascinated.

Also, see this December 7, 1958, Oklahoman article for some additional description. The general contractor was Secor Construction Co. of the city but the geodesic dome itself was being assembled by Dale Benz Inc. of Phoenix. The article says that the dome would include 625 diamond shaped panels of gold anodized aluminum and that its assembly began on May 7 and was amazingly expected to be complete only one week later.

The first geodesic dome was designed by German Walther Bauersfeld to house his planetarium which was completed in 1926 in Jena, Germany, but it was Richard Buckminster Fuller who coined the term “geodesic” and improved upon the science and and popularized it — he received a U.S. patent for his version of the dome in June 1954. He is shown in this July 2004 stamp with a domed head, the stamp commemorating the 50th anniversary of Fuller’s patent.

The first geodesic dome was designed by German Walther Bauersfeld to house his planetarium which was completed in 1926 in Jena, Germany, but it was Richard Buckminster Fuller who coined the term “geodesic” and improved upon the science and and popularized it — he received a U.S. patent for his version of the dome in June 1954. He is shown in this July 2004 stamp with a domed head, the stamp commemorating the 50th anniversary of Fuller’s patent.

I’m just guessing, but one would suppose that neither the bank’s 1957-1958 owners nor directors came up with the notion of using the then fledgling concept of a geodesic dome for the new bank. Most probably, that idea came from the architects they selected, the Oklahoma City firm of Bailey, Bozalis, Dickenson & Roloff. The 2003 documentation submitted to request registration of the building on the National Register of Historic Places indicates that Robert B. Roloff was the principal architect. Like Larry Nichols and Devon Energy decades later, the bank’s owners and directors apparently chose to make an architectural statement in their city, and they did. Admission of the dome to that august organization of American historic structures occurred in 2003.

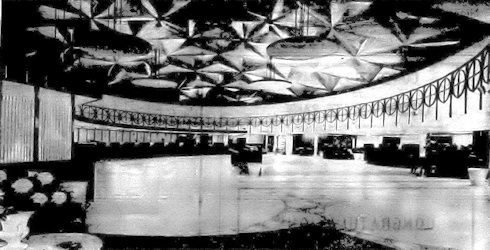

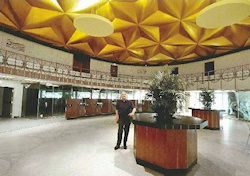

The initially planned opening date of the day after Labor Day did not happen, but, on Sunday, December 7, 1958, the new bank was open for public inspection, and on December 8 it was open for business. A photo from the December 7, 1958, Oklahoman shows a view of the interior.

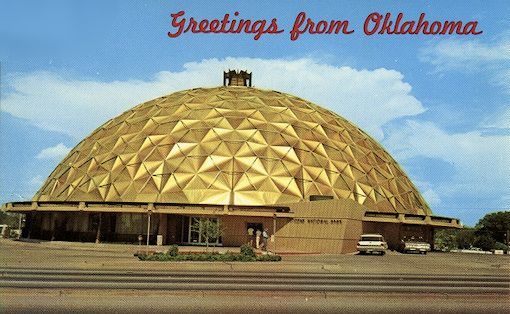

● Glory Days. Citizens State Bank opened for business at the Gold Dome on Monday December 8, 1958, following an open house to the public on Sunday, and it was a sight to behold. Although the gold color has faded now, the photos below from the Oklahoma Historical Society show that the building’s cap was indeed a brilliant gold.

|

|

Under the leadership of its board chairman and chief executive C.R. Anthony, Citizens continued its growth in the Gold Dome. In 1963, it shed its state bank status and became Citizens National Bank of Oklahoma City. In January 1970 Citizens added a trust department and the bank got its final name, Citizens National Bank & Trust Co. of Oklahoma City.

Although not owned by Citizens, several of its owners and directors joined to purchase the block south of the bank during 1960-1963. An August 2, 1963, Oklahoman article told why — those investors would build an office building, Citizens Tower, south of the bank. The article reported that the building would be 25 stories tall and would be designed by the same architect, Bob Roloff of Bailey, Bozalis, Dickenson & Roloff, that had designed Citizens State Bank only a few years earlier. It, too, would maximize gold anodized diamonds which were very compatible with the bank’s design. The article notes that B.D. Eddie was president of Citizens Tower Corporation and that other of Citizens’ officers and directors were involved with the project — C.R. Anthony, Myron Horton, L.A. Macklanburg, V.V. Harris, Jr., among others. This building, which was actually built to 21 stories, will be more particularly described in Oklahoma City Circa 1967 — Part 2.

At least by 1965, Citizens became the city’s 5th largest bank and 9th largest bank in the state — by 1976, Citizens’ deposits broke $100 million for the first time and it was the city’s 4th largest, behind Liberty, First National, and Fidelity. That remained true through 1979. A general January 13, 1980, Oklahoman article boasted that assets at metro area banks approached the $5 billion level in the 1979 year. The article quotes various metro banking officers as saying such things as,

[Wilfred] Clarke [of Fidelity] expects the Oklahoma City economy to continue to grow, describing it as “vigorous, diversified, expanding and strong.” * * * Jack Foster, president of fourth-ranked Citizens National Bank, attributed increased earnings to expansion of the bank’s commercial lending to firms able to pay the 15 percent to 17 percent interest on their loans. Foster said Citizens Bank’s earnings increased 22 percent before taxes last year, and 14.49 percent after taxes, compared with 1978 profits.

At the time, Oklahoma City metropolitan unemployment was only 2.9% (compared to the nation’s rate of just under 6%), and, as well, the city’s General Motors assembly plant went into production in May 1979 and added more than 5,000 jobs to metro employment.

The article also includes this then-benign observation …

Banking executives agreed that a booming rise in oil and natural gas exploration, production and land leasing contributed primarily to the increase in business activity and jobs.

A March 2, 1980, Oklahoman article presented detail on the performance of the 13 Oklahoma banks with assets of $100 million or more … published asset values, rounded down, are shown here …

| 1 1st NB, Okc — $1.5B | 5 Fidelity, Okc — $522M | 9 F&M, Tul — $210M |

| 2 Liberty, Okc — $1.2B | 6 4th NB, Tul — $317M | 10 Citizens, Okc — $155M |

| 3 BOK, Tul — $977M | 7 Utica, Tul — $283M | 11 Commerce, Tul — $137M |

| 4 1st NB, Tul — $909M | 8 1st NB, B’ville — $232M | 12 Union, Okc — $125M |

| 13 Penn Square, Okc — $114M | ||

The importance of #13 on the list, Penn Square Bank, would become known two years later when, on July 5, 1982, Penn Square Bank was declared insolvent, probably unknowingly foretold by the above quote in the January 13, 1980, Oklahoman article. A February 15, 1981, Oklahoman article reported that Penn Square Bank replaced Citizens as the city’s fourth largest bank during 1980.

In 1980-1981, oil prices dropped substantially and Penn Square Bank’s speculative oil and gas lending practices, mimicked or indirectly participated in by other banks, started a bank failure domino effect heard around the world — more about that in the next section.

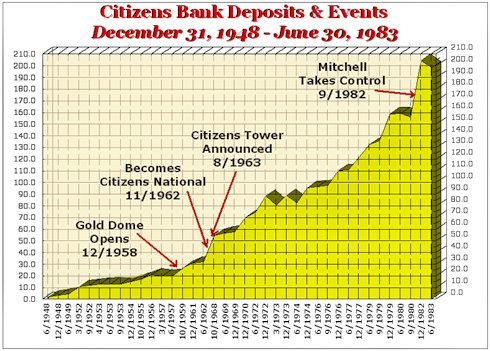

A snapshot of the remarkable rise of Citizens Bank deposits during its history through June 30, 1983, is shown below. Thirty-eight (38) Oklahoman ads and articles published during the period are the sources of this detail which I’ve collectively assembled in the chart below.

But, of course, deposits are not all there is in terms of a bank’s well-being. Citizen’s performance report on June 30, 1985, published in the July 25, 1985, Oklahoman show deposits at $232.4 million. Before the end of 1985, things at Citizens would change.

● Days of Masked Darkness & Failure. Although Citizens was far less aggressively involved with speculative lending than Penn Square Bank (what bank wasn’t?), in 1981-1982 it nonetheless had a substantial loan portfolio that became bad and had to be written off the books, meaning “pretty much uncollectible,” or something like that. Although Citizens did not begin to be referred to as a “troubled bank” until later, a September 12, 1982, article did note that Citizens charged off $4.3 million loans in 1981 and an additional $6 million in April 1982 “as a result of an examination of the bank completed that month.” The article did not identify who had made the examination, but, in the banking business, it is a given that a bank’s examiners are federal level banking types of folk.

A month earlier, an August 17, 1982, article reported that a bank holding company had been established to own Citizens which was called “Citizens National Bankshares Inc.” (actually, the name was Citizens National Bancshares, Inc.). Its stated purpose was to “allow Citizens to respond [with] more flexibility to the changing requirements of the banking public and to permit geographic diversification of bank operations,” said Citizens’ President, Jack Foster. An August 8, 1982, Oklahoman article reported that such holding companies had become a trend and gave further explanation of why the same was occurring. That article said,

Thomas G. Watkins, economist for the Kansas City federal reserve bank, said transfer of ownership to bank holding companies gives owners opportunity to pump more capital into the bank to raise its operating performance, and provides attractive benefits that, in effect, make it possible to buy a bank with a minority of cash and loans from the bank being purchased.

Probably that makes sense to those who are well-versed with banking practices, but to simple ears like mine it sounds more like, “Citizens just ain’t cutting the mustard without someone trying something new.” Probably, that’s just me.

• Dale E. Mitchell. Regardless, that development was the vehicle for the old regime to substantially exit and a new player to enter the unfolding Citizens drama, that being Dale E. Mitchell, then only 39 years old. The Oklahoman reported on September 12, 1982, that,

Oklahoma City banker Dale Mitchell has bought control of Citizens National Bank & Trust Co., and will take over top management of Citizens on Oct. 1, it was confirmed Saturday.

At the time, Mitchell was principal owner of the Bank of Commerce, Tulsa, and had a substantial interest in 1st National, Tulsa (see the table, above). Immediately before the move, he was the president and vice-chairman of First National Bancorporation (i.e., 1st National, Oklahoma City). A September 14, 1982, article said that he “jumped at the chance” to acquire the interest and become chairman and CEO of the bank and its new holding company. The article said,

Mitchell said the opportunity to buy control of Citizens came up quickly only a few weeks ago. “I jumped at it,” he said. ¶ He is resigning as vice chairman of the First Oklahoma Bancorporation, which owns the First National Bank & Trust Co., the state’s largest bank with $3 billion in assets. ¶ In seven years at First National, Mitchell rose from vice president to president and chief executive of the bank and vice chairman of the holding company. ¶ Mitchell acknowledges that he will take a substantial cut in salary and perquisites [ed. note: perks], but he also is starting, at age 39, a career as an owner and chief executive. He owns control of The Bank of Commerce and the neighborhood Gilcrease Hills Bank in Tulsa. ¶ The Bank of Commerce has assets of $270 million, and with the Citizens’ assets of $227 million, Mitchell has control of about $500 million in bank assets, with a joint lending limit of $4½ million. ¶ “We will be able to serve and keep our customers as they grow,” he said.

The article says that Mitchell characterized Citizens as “strong,” and he also said that “energy” loans had been reduced to 5%. As to the loans which had been written off, Mitchell said, “We expect good recoveries from those loans written off.”

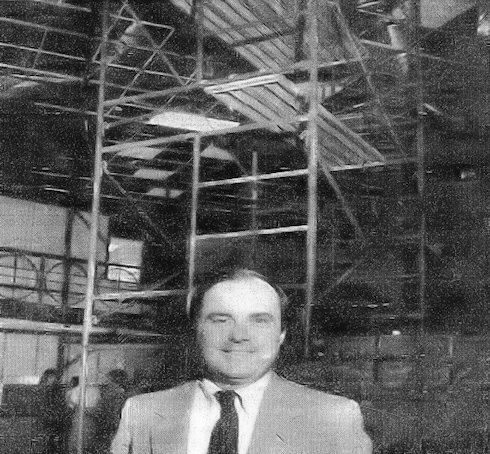

In fact, Citizens’ experiences after Mitchell assumed control were optimistic. Below is a photo from a March 3, 1983, Oklahoman article showing Mitchell during a remodel of Citizens’ interior which carried the headline, “Overhauled Citizens Bank All Set for Profitable Year.” Also in this regard, see this April 15, 1983, article.

The March 1983 article called 1982 a “disaster year” for Citizens, even though an Oklahoman reader could not have known that from reading 1982 Oklahoman articles pertaining to Citizens.

Despite the remodeling of the Gold Dome then underway, the article reported that Mitchell said,

“We have to get commercial and retail banking physically separated,” he said. “We need a new building, a square building, but we won’t build until we can afford a new building on our property.”

That remark did not bode well for future of the Gold Dome. Mitchell was evidently interested in seeing Citizens compete with the largest commercial banks in the state, and he was apparently interested in seeing the then defunct Penn Square Bank tower, then named Northwest Tower, but shortly to be renamed Citizens Plaza, become Citizens’ home.

Mitchell acknowledges the differences between executive rank in a $3 billion banking firm, with regional and even international connections, and once a highly profitable bank. He risked the change with the conviction a new era is coming in Oklahoma banking. * * * He is considering the idea of merging the Citizens and Commerce [of Tulsa] Banks into one holding company if the legislature passes the pending multibank measure, and making the Gilcrease Bank in Tulsa a branch of Commerce. ¶ Their consolidated assets have grown to just under $500 million; loans exceed $300 million and deposits are at $420 million.

The June 21, 1983, Oklahoman reported that a young, 32-year old, Timothy A. Baker had been appointed to be Citizens’ president. According to the article, his prior banking experience was vice-president of InterFirst Bank of Dallas in charge of its new loan production office, in addition to Mitchell’s appointment of Baker to be executive vice-president of Citizens in March 1983.

Very quickly, though, Mitchell was recruited to become the savior of Fidelity Bank by a search team headed by Dean A. McGee whom Mitchell had evidently impressed. Mitchell was elected chief executive officer of Fidelity Bank on July 7, 1983, for the apparent purpose of doing at Fidelity what he was at least perceived to have done at Citizens — shed bad energy loans, improve capitalization, and improve profitability. He acquired no stock in Fidelity and kept his holdings in other banks, including Citizens.

But, due to banking regulations, Mitchell could not maintain his leadership roles at Citizens while performing lifeguard duty at Fidelity. At Citizens, Baker became CEO at and Larry Hartzog became chairman of the board, and they led Citizens until Mitchell would return in November or December 1984 (Oklahoman reports varied).

A possible new physical future emerged for Citizens during Mitchell’s absence — but it is inconceivable that major moves would not have been informally discussed between Mitchell, Baker and Hartzog. Even if Mitchell had no official position at Citizens during his hiatus, he remained Citizens’ major owner. The December 2, 1983, Oklahoman contained the bold headline, “Northwest Tower Becomes Citizens Plaza.” Among other things, the article says,

A possible new physical future emerged for Citizens during Mitchell’s absence — but it is inconceivable that major moves would not have been informally discussed between Mitchell, Baker and Hartzog. Even if Mitchell had no official position at Citizens during his hiatus, he remained Citizens’ major owner. The December 2, 1983, Oklahoman contained the bold headline, “Northwest Tower Becomes Citizens Plaza.” Among other things, the article says,

Citizens National Bank & Trust Co. will rent 43,604 square feet of space in the new 21-floor Northwest Tower at Interstate 44 and Northwest Expressway and the name of the building will be changed to Citizens Plaza, it was announced Thursday. * * *Citizens will be designated the anchor tenant, occupying space on the ground floor and on the third and fourth floors. The agreement includes options for Citizens to lease space on the fifth, sixth and seventh floors for future expansion.

The article noted that negotiations had been underway since April (i.e., when Mitchell still held his positions at Citizens), so Mitchell was very clearly involved in the process. The article was vague as to whether the Citizens Plaza property would become the bank’s primary location or would only be a branch and it noted that, either way, the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency’s approval would be required.

A March 20, 1984, article reported that Citizens planned to move to Citizens Plaza in August, leaving the future of the Gold Dome in doubt. The article quoted Tim Baker as saying,

We will either have to refurbish it or tear it down and build a new building on the site. * * * We will maintain banking operations at NW 23 and Classen, but we’re just not sure if it will be a branch or a main headquarters. Our building is 26 years old and it was only meant to have a useful life of 10 to 12 years. The roof leaks, the pipes freeze and the golden dome is not as shiny as it used to be.

Once again, however, the article reported that the move was still waiting the approval of the U.S. comptroller. Status of the Gold Dome became a little clearer in a July 13 article. While noting that Citizens’ original intent was that Citizens Plaza was to become the bank’s headquarters, the application then pending before the comptroller was that the latter would be a branch and that the Classen and NW 23rd location would remain bank headquarters.

Thursday, Tim Baker, Citizens president, said executive offices and lending and trust operations will move to Citizens Plaza when the branch application is approved. He said the Golden Dome at the bank’s current site has inadequate space to handle the bank’s growth, but that it technically will remain the headquarters bank, at least for the present.

Although I admit to doing a bit of tea-leaves-reading here, my suspicion is that Mitchell, Baker and Hartzog wanted Citizens Plaza to become Citizens’ headquarters but that the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency had thrown a critical eye in that regard and that the application, which had been pending since December 1983, had been modified to gain the comptroller’s approval. Mitchell had made very clear that his goal was to make Citizens a player in commercial lending, inclusive of his ventures in Tulsa, particularly the downtown Commerce Bank. On at least four occasions during 1982 and 1983, a side-by side “Statement of Condition” for each bank was published in the Oklahoman, for ending quarters for December 1982, April 1983, June 1983, and September 1983. I’d hazzard a guess that the same thing was occurring in the Tulsa World. See this October 18, 1983, example, published during Mitchell’s stay at Fidelity. Under the common banner, “Oklahoma’s Banks That Mean Business,” were the statements,

There’s a new commercial banking network in Oklahoma. Bank of Commerce in Tulsa. And Citizens Bank in Oklahoma City. The first full-service commercial banking network that’s making history. A business-banking network specifically designed to give your company powerful new resources and expanded service. * * * If your company has branch offices in either the Tulsa or Oklahoma City areas, this new joint working relationship can be particularly advantageous foryou.

Very plainly, the earlier retail/consumer oriented goals of Citizen State Bank’s founders — implied in the choice of the name, “Citizens” — had changed under the Mitchell regime.

A festive black-tie dinner dance in the new Citizen Plaza penthouse (actually, there were two penthouse floors, but who’s counting?) a day or so before December 9 served as sort of a christening party for the new tower. The event was described in a December 9, 1983, Oklahoman society page article like this:

Peter Duchin and his orchestra were flown in from New York to add their special music to the sophisticated atmosphere. * * * It was definitely the black-tie invitation that motivated the “in” crowd to deck themselves out in their holiday finest, put on their dancing shoes and spend a delightful evening high in the sky. * * * Guests could circle the penthouse and take their pick of such delicacies as lobster, lamb chops, thin sliced beef …

Etc., etc., etc. Chances are good that no readers of this article were invited to the ball, but the event was attended by Dale Mitchell and Cleta Deatherage among many others who the article described as being in the “in” crowd. Andy Coats, to be mentioned later, was present, as well. As for your and my absence of an invitation … oh, well … maybe next time or in some other life we too will have such an opportunity.

Back to topic. I couldn’t determine the reason for the branch opening delay — comptroller issues or something else — but Citizen’s branch bank at Citizens Plaza did not open until almost a year after the gala party described above. A November 22, 1984, article said that Citizens would formally open its new branch at Citizens Plaza on December 3, although the article also said that limited operations were already occurring there as of the article’s date. A December 9, 1984, Oklahoman ad by Citizens publicly announced the opening of the new branch office at Citizens Plaza.

By that time, Mitchell had finished his business with Fidelity — which is a story for another day, but, in a nutshell, during his time at Fidelity was acquired by and merged into BankOklahoma Corp. (Bank of Oklahoma) of Tulsa — and had returned as Citizens’ chief executive officer and chairman of the board. As part of his leaving Fidelity, he was given a $1 million promissory note which note would become important in two of the later criminal charges against him. Notwithstanding that a November 7, 1984, article already said that Mitchell was then Citizens’ chairman, and that his wife, Cleta Deatherage Mitchell, was the bank’s general counsel and a vice president, a later November 22, 1984, Oklahoman article reported that Dale Mitchell had been re-elected chairman and chief executive of Citizens, that James Burgar, formerly with Fidelity, was named president, and that former president Timothy A. Baker had relinquished his presidency and chief executive positions to become vice chairman of the board of directors, all effective December 1. In the article, Mitchell announced that Citizens would formally open its Citizens Plaza (called Tower in the article) branch on December 3 although limited operations were already occurring there when the article was written.

As for Mitchell after his return to Citizens, Oklahoman articles — and there were several — mainly show his involvement in the dispute between Dean Krakel and others with several prominent members of the board of the National Cowboy Hall of Fame for control of the Cowboy Hall and the possibility that it might leave Oklahoma City. Mitchell was the Cowboy Hall’s board treasurer and Citizens had a substantial loan to the Hall. That’s quite a fascinating story all by itself but it won’t be further gotten into here.

As for banking, only four stories about Citizens appeared in the Oklahoman in 1985, plus Statements of Condition. Recalling what has been previously said about Mitchell’s interest in the Tulsa’s Bank of Commerce, a May 23 article described steps being proposed and taken to bolster the Bank of Commerce and other banks with a linkage which would potentially include Citzens. I’ll get to the other 1985 Oklahoman stories shortly.

Statements of Condition published in 1985’s Oklahomans were no longer paired with similar statements about Commercial Bank of Tulsa. Citizens’ 1985 published statements showed deposits, loans & reserves for loans, and total assets as follows:

| Report Date | Deposits | Loans & Reserves | Total Assets |

| 3/31/1985 | $235.672M | $172.350M | $256.610M |

| 6/30/1985 | $232.451M | $168.075M | $253,551M |

| 9/30/1985 | $216.021M | $155.827M | $229.973M |

| 12/31/1985 | $159.675M | $146.503M | $204.994M |

The December 31, 1985, Statement of Condition was the last to be filed by Citizens in the Oklahoman. A June 13, 1986, article reported that, “Citizens has not published its bank call (ed. note: statement of condition?) for the first quarter. Most Oklahoma City banks published theirs in April.” None were published during the remainder of 1986, either.

The second 1985 Oklahoman article appeared on December 4 and was evidence of internal discord within the Citizens organization. The article reported that, on November 18, two officers had resigned, Jan L. Miller, executive vice president for lending, and Jim D. Burgar, president of the bank. The article says that, “Burgar said he left because of disagreement over how the bank ought to be run.” Mitchell then assumed Burgar’s role.

The third 1985 Oklahoman story about Citizens appeared on December 17 and that article marked the end of Mitchell’s leadership roles in Citizens. The article reported that the directors of Citizens Bancshares Inc., which owned the bank, voted to approve an option agreement with Shawnee banker H.E. Gene Rainbolt to buy control of Citizens — later articles indicated that meant an option which Rainbolt could exercise within a 5-year period to buy 55% of Citizens but it was an option that Rainbolt never exercised — and that the directors elected Ray F. Bauer, Rainbolt’s choice, to be president and chief executive officer of Citizens. Mitchell was replaced as President although Mitchell would remain chairman of Citizens National Bancshares until the Federal Reserve Board would approve Rainbolt as chairman and chief executive. Bauer’s appointment as chief executive already had the approval of the regional director of the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency, so this development must have started well before the December 17 article.

The last 1985 article, December 29,1985, was about what Dale Mitchell would do with himself upon his departure from Citizens. Read the article for more particulars, but a synopsis is that he would become a professional adviser in the following regards:

“I’m going to spend all my time trying to interpret to clients how to invest and how to sustain those investments,” he said. “I intend to concentrate on revitalizing businesses that are already here in Oklahoma, those with 25 workers who can grow and avoid going broke.”

Good luck with that — see the Days of Corruption section, below.

• Post-Mitchell Last Days. Mitchell was effectively gone from Citizens by December 16, per a December 17, 1985, article, and the new person in control seemed to be H.E. Gene Rainbolt. Rainbolt was a successful Shawnee banker who had created a consortium of banks within a holding company named United Community Corp. which involved banks in several Oklahoma cities, e.g., Shawnee, Guthrie, Konawa, McAlester, Sand Springs, Seminole and Stillwater. If he was able to make substantial changes at Citizens during his tenure as chair of Citizens Bancshares, chances were good that he would have exercised his purchase option for 55% of Citizens and would have added Citizens to his stable of banks. It is difficult to imagine that he would have become involved with Citizens’ fate for any other possibility.

His view of Citizens was different than Mitchell’s and was more akin to the original Citizens State Bank incorporators when C.R. Anthony and others formed the bank in 1948. But his view would not prevail — by May, it became evident that a majority of the board of Citizens Bancshares did not share Rainbolt’s aspirations for the bank.

A March 2, 1986, Oklahoman article anticipated federal approval and a March 20 article reported that federal approval of the Rainbolt development had been granted. The direction that Rainbolt wished to take Citizens was described in the March 2 article by Bauer who had been acting President for about two months:

He [Bauer] said Citizens is on a reducing regimen, changing its goal of becoming a $300 million commercial lending institution to a community bank of between $200 million and $225 million to serve smaller businesses and consumers. ¶ He said the Golden Dome at NW 23 and Classen comprises “our main bank, our main offices and the primary source of deposits and lending. ¶ Those people have been our customers and will continue to be,” he said. “Our goal is to re-emphasize a community banking philosophy. We intend to increase installment lending. It is prudent to take care of our core depositors and borrowers.”

Perhaps that would have happened had Rainbolt had greater control but, as it was, an August 8 article reported that Bauer, Rainbolt’s choice as bank president, had been replaced by the Citizens Bancshares board in May and that board members selected Wallace H. Emerson to serve as president instead. Although Rainbolt continued as board chairman after that board action in May, his role became passive and the August 8 article reported that Rainbolt resigned his chairmanship of Citizens Bancshares. Rainbolt’s reasons were reported in the article.

“We saw it as an opportunity, and the board saw it a different way,” he said. “We picked our person and our approach, and if that was not what they wanted to follow, that was sufficient to terminate our agreement.”

Earlier articles, in June, were less specific about those factual developments but those June articles evidenced that the bank’s attorney, Terry W. Tippens, had become the bank’s principal spokesman, he doubtless speaking on behalf of the board. In the June 13 article mentioned previously, it was reported that the Oklahoman had obtained the bank’s first quarter 1986 report filed with the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency, principal regulator of U.S. banks, prepared during Bauer’s regime. Even though the submitted report had not been made publicly available, it was a “public record,” and that fact entitled the Oklahoman to obtain the information. The report was not a good one for citizens.

The article’s main headline read, in bold print, “Citizens Bank Net Worth Drops 68%,” and the secondary headline was, “Report Indicates Problems in Loan Portfolio.” Emerson, Bauer’s successor as bank president, would only say, “I have no comment,” to Kevin Laval, the Oklahoman’s reporter. Lawyer Tippens said that the figures were based on information prepared by Bauer’s staff and that they had been withdrawn for re-evaluation. The article also noted, however, that Ellen Stockdale, spokesperson for the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency, “said such reports are public records that can be revised but not withdrawn.”

“Oh, come on, Terry,” I was thinking as I read this article — Tippens, a top-flight lawyer in this field, would have known better, and his remarks only represented a failed transparent attempt at window dressing, in this writer’s opinion.

The report reflected that during the first quarter Citizen’s net worth dropped from $12 million to $3.8 million and that assets had dropped to $179 million. The article said that federal regulations require that “a bank of Citizens’ assets * * * maintain net worth of $10.7 million.” If that’s so, that means that Citizens was under-capitalized at the end of March by $6.9 million.

The article also said,

Tippens also said a plan has been developed for increasing the bank’s net worth, although he would not discuss the proposal in detail.

“But, wait, there’s more” (ala Ron Popeil). The article goes on to say,

The Oklahoman obtained a [ed. note: another] report from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, which regulates bank holding companies. Martha Conner, of the Fed’s Freedom of Information office, said the report was written by the FDIC and consists of data filed with the FDIC by the bank. ¶ The report shows problems in Citizens’ loan portfolio and, as a result, weakness in the ability to produce income. When a loan is lost, the income it would produce is also lost. ¶ The report shows that the bank acknowledged $7.6 millions of loans — most of them commercial lendings — as losses during the quarter. * * * With the net loss, equity capital — which was $5.9 million at the beginning of the period — fell to a negative $7.8 million.

This report was not a report by Citizens, it was a report by the FDIC, and neither Tippens nor his client Citizens Bancshares would have any control over withdrawing or revising that federal report.

These things, and other items mentioned in the full June 13 article, explain the reason for Terry Tippens’ fancy-dancing.

But the dance would not work. Although an Oklahoman article as late as August 12 indicated that Dallas-based MCorp might be considering acquiring Citizens Bank and probably as part of the new regime’s plan, it was too little too late. From the federal perspective, several things were possibly, and I think probably, seen as true and as probable givens:

- Federal authorities did not like what had occurred at Citizens during the several months before December 1985.

- As evidence of that hypothesis, by December 1985, Federal authorities had already pre-approved Bauer as president before he was appointed to that position — such kinds of things do not happen quickly at the federal level.

- Federal authorities liked Bauer’s proposed appointment and approved the proposed arrangement with Rainbolt.

- Both Rainbolt and Bauer had more modest visions of what Citizens’ goals would become.

- Bauer was gone from Citizens in May and Rainbolt was gone in August. By May, the board majority at Citizens Bancshares had assumed control.

- This new regime was perhaps more interested in Mitchell’s commercial model than Rainbolt’s consumer model (I’m just guessing).

- First quarter 1986 was a disaster for Citizens.

- Regardless of any hype from Tippens, nothing had happened after the first quarter to present a more promising Citizens to federal officials.

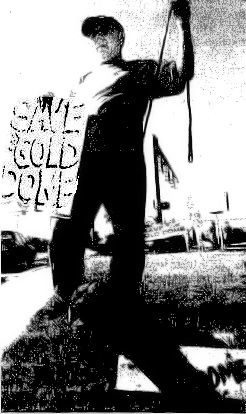

● Citizens Fails On August 14. Whether my above analysis of the situation is correct or not, Citizens National Bank & Trust Company of Oklahoma City was closed by federal regulators at 5:00 p.m. on August 14, 1986. A pair of Oklahoman articles on August 15 gives the detail — the main front page story and the chart showing failed Oklahoma banks on page 21. Citizens’ failure was the 3rd largest in state history (Penn Square Bank, Oklahoma City, July 5, 1982, $470 million deposits; First National, Oklahoma City, July 14, 1986, $1.5 billion deposits; Citizens on August 14, $158 million deposits). The page 21 chart shows that Tulsa’s Bank of Commerce in which Mitchell had a major interest was closed on May 8, 1986, with $126 million deposits, and the relevance of that bank closure will become evident in the next section.

The front page article contained a Bulletin that Liberty Bank, Oklahoma City, had purchased Citizens the better assets of Citizens from FDIC. Citizens’ Gold Dome and its branch at Citizens Plaza would reopen on Monday, August 18, but as branch banks of Liberty National Bank & Trust Co. of Oklahoma City and the once proud bank originally known as Citizens State Bank would be seen no more.

● Days of Corruption. I’m not sure that’s the best title for this section since I’m not interested in being judgmental — but, sadly, a rose by any other name is still a rose. The names mentioned in this section are associated with Dale E. Mitchell’s name in one way or another.

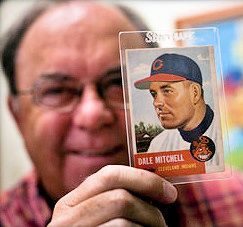

Dale E. Mitchell. Dale is one of the sons of L. Dale Mitchell, a former baseball great at the University of Oklahoma who became a major league baseball icon and for whom the L. Dale Mitchell Baseball Park at the University of Oklahoma is named. In this October 2010 picture, the son is in the background and the father is shown in the foreground in a Cleveland Indians baseball card. The son, too, played baseball at the University of Oklahoma, but the story here is not about baseball.

Dale E. Mitchell. Dale is one of the sons of L. Dale Mitchell, a former baseball great at the University of Oklahoma who became a major league baseball icon and for whom the L. Dale Mitchell Baseball Park at the University of Oklahoma is named. In this October 2010 picture, the son is in the background and the father is shown in the foreground in a Cleveland Indians baseball card. The son, too, played baseball at the University of Oklahoma, but the story here is not about baseball.

After Dale Mitchell’s 1983 divorce from his first wife, Mary Ellen Mitchell, Mitchell married Cleta Deatherage in March 1984. Deatherage was then a Norman up-and-commer in the Democratic party — she served eight years as member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives (1976-1984) and was seen by many as a beacon of progressiveness in Oklahoma and in the Democratic party, generally. She felt so strongly about the Democrat party that, as a premarital condition of her changing her last name to Mitchell upon marriage, she insisted that Dale switch his party affiliation to Democrat before their marriage, and he obliged. A March 9, 1984, Oklahoman article reported Deatherage as saying, “He wanted that [name change] and it wasn’t negotiable. It was important to him.” At their marriage, Dale was 41 and Cleta was 33 years of age. A few months earlier, both attended the gala black-tie invitation-only dinner-dance for the opening of Citizens Plaza as was reported in the Oklahoman on December 9, 1983. After their marriage, in November 1984 the Mitchells purchased a home at 6715 Avondale Drive in Nichols Hills, leaving their Norman residence. Oklahoman, November 7, 1984. According to the County Assessor’s records, on November 1, 1984, Cleta Deatherage Mitchell became the owner of the Avondale Drive property and she sold the property, valued around $1 million, for only $310,000 on May 1, 1987. Go figure.

After Dale Mitchell’s 1983 divorce from his first wife, Mary Ellen Mitchell, Mitchell married Cleta Deatherage in March 1984. Deatherage was then a Norman up-and-commer in the Democratic party — she served eight years as member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives (1976-1984) and was seen by many as a beacon of progressiveness in Oklahoma and in the Democratic party, generally. She felt so strongly about the Democrat party that, as a premarital condition of her changing her last name to Mitchell upon marriage, she insisted that Dale switch his party affiliation to Democrat before their marriage, and he obliged. A March 9, 1984, Oklahoman article reported Deatherage as saying, “He wanted that [name change] and it wasn’t negotiable. It was important to him.” At their marriage, Dale was 41 and Cleta was 33 years of age. A few months earlier, both attended the gala black-tie invitation-only dinner-dance for the opening of Citizens Plaza as was reported in the Oklahoman on December 9, 1983. After their marriage, in November 1984 the Mitchells purchased a home at 6715 Avondale Drive in Nichols Hills, leaving their Norman residence. Oklahoman, November 7, 1984. According to the County Assessor’s records, on November 1, 1984, Cleta Deatherage Mitchell became the owner of the Avondale Drive property and she sold the property, valued around $1 million, for only $310,000 on May 1, 1987. Go figure.

This was her second marriage, as well. It has been reported that her first husband was gay, and it has been suggested that that fact may have influenced her metamorphosis from a liberal Democrat into an ultra-conservative Republican activist after she and Dale left Oklahoma, but I’m offering no opinion about that. After first moving to New York, they eventually settled in Washington, D.C., as will be discussed below. As has already been mentioned, after Mitchell left his Fidelity Bank duties and resumed his positions at Citizens Bank in November or December 1984, Cleta Deatherage Mitchell became General Council for and a vice president of Citizens National Bank & Trust Company.

Mitchell was eventually charged with bank fraud, in 1992, and one might think that just telling a bit about that trial and its outcome would be a simple thing to do — but, the problem is, that such an approach would leave out significant parts of the story which, before the end be told, has elements of a melodrama, a very interesting con-man (Bazarian, not Mitchell), an ex-wife and a bankruptcy thrown in.

I’m saying that a very engaging television soap opera could easily be crafted upon the Mitchell story unfolding here.

I’ll start with Mitchell’s ex-wife. As alluded to above, following a 19-year marriage, Mitchell and his first wife, Mary Ellen, were divorced in Oklahoma City on August 24, 1983. But, in July 1985, Mary Ellen filed a petition to vacate that decree which wasn’t the result of a trial but of a negotiated divorce agreement. The July 12, 1985, Oklahoman reported that Mary Ellen filed a petition to vacate that decree, alleging that Dale had omitted assets, “knowingly and with the intent to mislead” Mrs. Mitchell into entering into the agreed divorce settlement. Her lead attorney was Los Angeles attorney Marvin Mitchelson who came to fame during his representation of California actor Lee Marvin’s paramour in her claim against the actor for what has come to be called, “palimony.” Dale Mitchell’s attorney was Mayor Andy Coats. The Oklahoman does not contain a report of how the post-divorce litigation was resolved, but in Mr. Mitchell’s December 31, 1986, bankruptcy petition, one of the creditors he identified was Mary Ellen whom he identified as a $341,547 creditor.

I’ll get back to the bankruptcy shortly after moving fast forward to July 1988 and 1991 — and, yes, the bouncing ball is a bit hard to follow. The July 19, 1988, Oklahoman reported that Dale E. Mitchell and Timothy A. Baker had agreed to be banned for life from employment at federally insured banks. The article said,

Specifically, the [U.S.] comptroller [of the currency] said the two arranged loans that were concealed from the bank’s board and officers. It said the loans, which it described as unsafe and unsound, were intended to “further Mr. Mitchell’s financial interests in violations of banking law and their fiduciary responsibilities to the bank.” ¶ The comptroller said the loans resulted in $1 million of losses for Citizens, which was declared insolvent and closed August 14, 1986, and another $400,000 of losses for the bank’s holding company.