A Book Review by Doug Loudenback

Who doesn’t savor extravagantly entangled murder mysteries, nefarious melodramas in which big business is allegedly unworried about harming the public, and yarns of political corruption-crime-and-intrigue?

I’m not presently thinking of stories like the modern-day Sherlock on PBS, or movies like 1979’s The China Syndrome, or Netflix’s House of Cards — as much as I enjoy them all. Right now, I’m thinking, “Ya got trouble, my friend, right here, I say, trouble right here in River City.” We’ve had real true-to-life similar troubles right here in Oklahoma River Cities!

That kind of trouble is what Oklahoma’s Most Notorious Cases is all about. Hereafter, I use “Notorious” to reference the book title. In it, Oklahoma City author Kent Frates chronicles six of those true-story troubles — those befitting his label of “Oklahoma’s most notorious cases.” He identifies them as …

1. Machine Gun Kelly & the Urschel Kidnapping

2. U.S. v. David Hall

3. The Girl Scout Murders

4. The Karen Silkwood Case

5. The Sirloin Stockade Murders

6. The Oklahoma City Bombing

… and this is my review of and a few notes about Mr. Frates’s book, Oklahoma’s Most Notorious Cases (The RoadRunner Press, Oklahoma City, 2014).

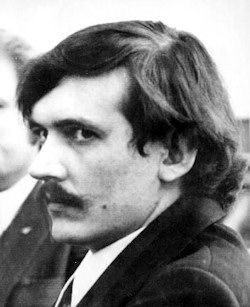

First Booksigning. It was at the Full Circle Bookstore, Oklahoma City, Tuesday, November 11, 2014, at 6:30 p.m. — which is to say, a few days ago. My intention was to have this review done well before then, but that didn’t work out. I should have been too embarrassed to attend, but I sucked it up, attended the booksigning, and got the photo of the author, at the left. Other notable lawyers — (Honest) Don Davis, H.K. Berry, and John Michael Williams — were present while I was there. Probably, other booksignings will occur, and I will update this paragraph as I learn of them.

First Booksigning. It was at the Full Circle Bookstore, Oklahoma City, Tuesday, November 11, 2014, at 6:30 p.m. — which is to say, a few days ago. My intention was to have this review done well before then, but that didn’t work out. I should have been too embarrassed to attend, but I sucked it up, attended the booksigning, and got the photo of the author, at the left. Other notable lawyers — (Honest) Don Davis, H.K. Berry, and John Michael Williams — were present while I was there. Probably, other booksignings will occur, and I will update this paragraph as I learn of them.

Booksigning UPDATE! The next booksigning: Saturday, Nov. 29th, 3 – 4:30 p.m.

Best of Books, Kickingbird Square, 1313 E. Danforth Road, Edmond 405.340.9202 (At least I’m on time for this one.)

The Book’s Website:

http://www.okmostnotoriouscases. com/ … at this website, in addition to purchasing the book, you can read several pages of text in the Girl Scout Murders case and view a few images in the book.

Perhaps because I wrote such glowing words about his June 2014 issue of Common Cause, Kent thought that I would be as generous were I to review his latest literary offering, Oklahoma’s Most Notorious Cases. If he did think that (and he probably didn’t — he is a stand-up guy), he was certainly correct. Having received his October 7 invitation to review his latest book, and having finished my reading and analysis, the briefest review is simply this: I just loved this excellent Oklahoma (primarily Oklahoma City) history book.

Naturally, I am obliged to be more particular and critical in an objectively written book review, so let’s have a closer look.

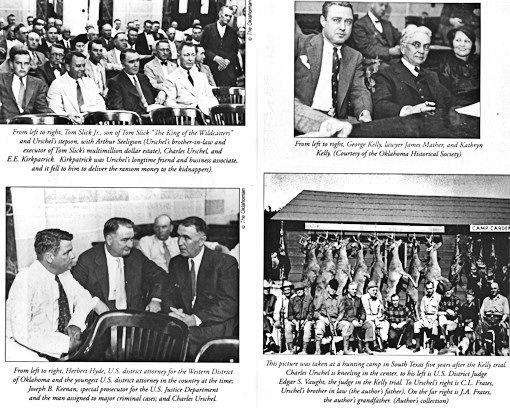

The Book Itself. This hardback book is 338 pages long, plus 11 pages of chapter notes, plus 16 pages of mostly small but 30 high quality photos on glossy photo paper. That makes the actual page length 365 pages, not including the introductory pages to each chapter four of which begin with a poem penned by Mr. Frates. Paper and print quality are excellent. Graphics quality is also excellent, as shown by the reduced-size scan of two pages below:

My favorite of the above photos is the lower right hunting trip — Urschel is kneeling in the center and to his immediate right is the author’s father, C.L. Frates — the resemblance between the author and his dad is remarkable.

The book size is approximately 6″ x 9.” The price is $24.00 U.S. dollars, $26 Canadian. It is also available at Amazon at a slightly lower price. For a quality hardback history book such as this book is, at any of these prices, it is quite a steal.

Why We Care About The Trouble. In the book’s Introduction, Kent says,

Legal cases are, of course, about events, but they are more about people. They have heros, and they have villains … sometimes really bad villains. Who the good guys and the bad guys are goes to the heart of any good legal case, or true story. How often has someone picked up the newspaper or turned on the television and asked himself, How could anyone do that? How could anyone be that evil?

It may well be fortunate that we cannot know the thought process of the most vicious criminals, but it would be disingenuous to pretend that their crimes do not catch and hold our attention. As much as we’d like to understand what drives the villains, we are equally, if not more so, enamored by the heroism, resourcefulness, and pure tenacity of the law enforcement professionals who bring down the same criminals. It is somehow this ying and yang of our justice system that creates memorable cases.

In a world of instant news and constant communication we must remember it was not always like this. The shrill buzz of 24/7 coverage is a relatively new phenomenon. Newspaper stores, word-of-mouth accounts, radio bulletins, and early-day television reports spread the news in less graphic and slower ways. Trials remain a source of mass entertainment, but there was a time when people actually traveled from town to town to attend them, as fans might travel for a sporting event. [Emphasis supplied]

Kent didn’t put it this way, but the truth is (I think) that most of us, including me, are voyeurs — we like to watch — and our attention is drawn to both humanity’s dark and light sides at the same time, for whatever reason. We like to watch Darth Vader as much as we do Luke Skywalker.

The Author’s Choices. The preface page to his Introduction contains this definition of “notorious,” doubtless derived from some unnamed dictionary:

Notorious: well-known or famous especially for something bad: generally known and talked of; especially: widely and unfavorably known: from the Latin noscere to come to know

In the Introduction, he amplifies his intended meaning and the reasons he chose the six cases he did from Oklahoma’s (and, largely, Oklahoma City’s) history:

What then makes for a notorious case? Some trials are so universally well known, we simply refer to them as the “Trial of Galileo” or the “Scopes Trial.” But to rise to the level of notorious requires that a case be more than just ubiquitous, think, “Lizzie Borden” or “Charles Manson,” “John Hinckley Jr.,” or “O.J. Simpson.” Such cases carry a hint of evil, an indifference to one’s fellowman not found in your average murderer or corrupt politician or thief. [Emphasis supplied]

* * *

The cases chosen for this book cover a wide swath of Oklahoma history from 1933 to 2004. Some older cases were rejected because of the lack of sufficient reliable records.

Doubtless, the author’s six choices match all of his requisite standards — even though one could make a case for the addition of populist Governor Jack C. Walton, Oklahoma’s fifth Governor, who was impeached by the Oklahoma House of Representatives, and then tried, convicted, and finally removed from office by Senate on November 19, 1923, after serving only eleven months in office. The story of this politician and his career has all the earmarks of being “notorious” — plus, evidence of evil was ample on all sides surrounding his fascinating eleven-month term in office — including Walton’s imposition of martial law, his placement of armed National Guardsmen around and on top of courthouses, even his commandeering The Tulsa World newspaper for a time, his suspension of the writ of habeas corpus and massive corruption in office, as well as the KKK’s involvement both in and out of the Oklahoma Legislature. Other scholars have noted that, most probably, a majority of Oklahoma House and Senate members were members of the KKK during the time of Walton’s tenure as Governor. Although I would have relished reading Mr. Frates’s description of this period of Oklahoma City history, I must give him a pass for not doing so because, after all, Notorious is his book and not mine.

As to Kent’s content choices, I’ll make a few comments, but I’ll spend more time with the first case than the others — partly because I want to illustrate an exemplary case, but also because the Heritage Hills Urschel home is only three blocks from where I live in Mesta Park.

Case #1 — Machine Gun Kelly & The Urschel Kidnapping, Chapters 1-11.

The Kidnapping, Not Your Normal Hostage, The FBI, The Ransom, The Hunt, On the Run, The First Trial, Capturing the Kellys, The Kelly Trial, Aftermath, Kathryn & Ora Set Free

Some sources say that George Francis Barnes Jr. was born on July 18, 1895, in Memphis, Tennessee — Notorious says that he was born on July 14, 1900, in Chicago, Illinois. Either way, he changed his name to George R. Kelly and came to be popularly known as Machine Gun Kelly. He died on July 18, 1954, in Leavenworth, Kansas. His last wife, Kathryn, co-conspirator and probable planner of the kidnapping but not present when it occurred, was born Cleo Mae Brooks in Saltillo, Mississippi, in 1904. A third principal bad guy and participant in the actual kidnapping was Albert Bates, born October 16, 1893.

About Kathryn, Notorious notes that J. Edgar Hoover said, in his 1938 book, Persons in Hiding:

Several years ago, thousands of our citizens shivered in fear of a kidnapper whose name had much to do with the terror he engendered: he was called Machine-gun Kelly. However, there was someone far more dangerous than Machine-gun Kelly. That was Machine Gun Kelly’s wife.

Anecdotally, I’ll mention that another lawyer friend of mine, John Brewer of Oklahoma City, whose father had been married to Kathryn before she married Kelly, related to me that Charles Urschel may have been an afterthought concerning their pending kidnapping. He says:

Some time prior to the Urschel kidnapping, Kathryn and George showed up in Pauls Valley [Oklahoma] with the intention of kidnapping my older brother. A hotel employee overheard the plotting, told my dad, and my dad told the local sheriff. Kathryn and George were told to leave town. Urschel was next in line. Actually Urschel was MUCH better off financially than my dad.

The actual victim-in-waiting proved to be Charles F. Urschel. He lived in Oklahoma City at 327 N.W. Eighteenth Street with his second wife, Berenice. Urschel was born in Hancock County, Ohio, on March 7, 1890, and died on September 16, 1970, in San Antonio, Texas.

Frates doesn’t quantify Urschel’s wealth, but he does note that the Cushing oil field was developed by Urschel and Tom Slick and that, in 1919, “it accounted for seventeen percent of the United States and three percent of world production of oil.” Think about that for a moment — 17% of oil production in the United States and 3% of the world’s. That’s one heck of a lot of o’ earl!

The pair continued their business partnership until Slick died in 1930, leaving Bernice as his widow. After Urschel’s first wife died in 1931, Charles married Berenice, Slick’s widow, thereby combining their vast fortunes.

The author describes the Urschel home as a “mansion,” and indeed it was, and it so remains. The Oklahoma County Assessor’s records state that the home contains 6,330 square feet. This photo was taken October 2014. The Oklahoma City Historical Preservation Commission’s marker on NW 18th states that it was built in 1923, was originally owned by Tom Slick, and would later be owned by US Senator Robert S. Kerr.

The author describes the Urschel home as a “mansion,” and indeed it was, and it so remains. The Oklahoma County Assessor’s records state that the home contains 6,330 square feet. This photo was taken October 2014. The Oklahoma City Historical Preservation Commission’s marker on NW 18th states that it was built in 1923, was originally owned by Tom Slick, and would later be owned by US Senator Robert S. Kerr.

This view from Google Earth shows the spacious mansion from the air.

This view from Google Earth shows the spacious mansion from the air.

While playing a late-night hand of bridge within the above home’s screened back porch on July 22, 1933, at 11:15 p.m., Urschel and, initially, his friend Walter Jarrett, were abducted — Jarrett was released some hours later in eastern Oklahoma County once the abductors managed to figure out which of the pair was actually Urschel, the intended target of the kidnapping. A $200,000 ransom was demanded, paid, and, eventually, somewhat recovered. The author notes that the sum would be the equivalent of about $3,000,000 in today’s currency. He deliciously takes his readers through the lives of the people and events surrounding the first FBI kidnapping case and the first criminal trial to occur in Oklahoma City’s then new federal courthouse — quite possibly setting a land speed record for “speedy trial.”

These comments just skim the surface of this fascinating case — and, no, Kelly did not coin the phrase, “G-man,” as in, “Don’t shoot, G-man.” Most probably, that phrase can be attributed to Hoover and his then infant FBI organization.

Many internet sources exist for the events described in this Notorious case, but given that (1) the author’s research is extensive, and (2) he is a nephew of Charles and Berenice Urschel and communicated with Charles about it before his death, my expectation is that the author’s accounts are the most accurate of all available.

Case #s 2-6. This review is already too long so I’ll make fewer comments about the other cases in Notorious, below.

Case #2 — United States v. David Hall, Chapters 12-24.

Case #2 — United States v. David Hall, Chapters 12-24.

The Road To Success, Politics, Governor Hall, Kickbacks, Bribes & The IRS, Political Defeat, Wired, The Sting, The Payoff, Federal Charges, The Trial, The Defense, Guilty, Payback & Denial

This case describes the legacy of the 20th Governor of Oklahoma (1/1/1971 – 1/13/1975). It is a story of money, bribery, kickbacks, and extortion, all wrapped up in a governor’s clothes. It tells the story of what can happen when blind ambition is coupled with very shallow pocketbooks in the power of the office of the Governor of Oklahoma. Near the end of his term in office, Hall was already the subject of federal grand jury proceedings — but the Fall 1974 investigation didn’t end there. Amazingly, Hall engaged in one of his most arrogant schemes during his last 1½ months in office, he knowing all the while that he was under intense scrutiny by federal authorities.

On January 13, 1975, he served his last day in office. Three days later he was indicted on four counts in federal court involving extortion, conspiracy to use interstate commerce to carry on an unlawful activity, and bribery. His trial began on February 24 and the jury was given its instructions on March 12. On March 14, verdicts of guilty were returned on all counts. All appeals failed and, after serving only 18 months of his 4-year sentence, he was released from federal prison. He and his wife are living out the remainder of their lives in southern California, Hall still professing his innocence.

Case #3 — The Girl Scout Murders, Chapters 25-37.

Case #3 — The Girl Scout Murders, Chapters 25-37.

The Crime, The Investigation, Gene Leroy Hart, Manhunt, Homeboy, Captured, The Prosecution, Preliminary Hearing, Newly Discovered Evidence, The OSBI Reports, The Trial, The Defense, Controversy

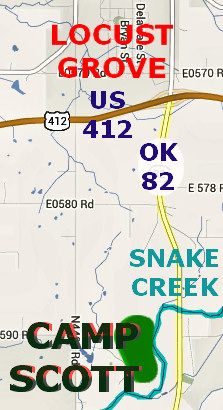

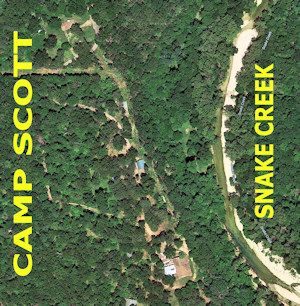

Late night, on June 13, 1977, three young Girl Scouts camping at Camp Scott south of Locust Grove in Mayes County were sexually molested and brutally murdered. They were Lori Lee Farmer (8 years old), Michelle Heather Guse (9), and Doris Denise Milner (10).

This is the only case in Notorious which does not have a metropolitan Oklahoma City venue.

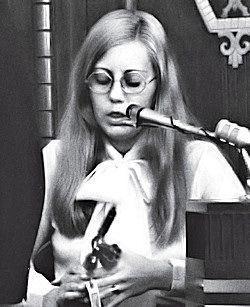

That said, the only person ever charged with the murders, James Leroy Hart, was defended by a then-young Oklahoma City lawyer, Garvin Isaacs, who would make his name on this case.

This case is as much a description of inept investigation and prosecution as it is with the only person charged with these brutal crimes — Gene Leroy Hart — who was eventually charged and acquitted. The author notes at the outset:

This case is as much a description of inept investigation and prosecution as it is with the only person charged with these brutal crimes — Gene Leroy Hart — who was eventually charged and acquitted. The author notes at the outset:

When a heinous crime occurs, and a suspect is charged and later found not guilty, public doubt always persists as to whether the defendant did or did not commit the crime. This is especially true when no other suspects emerge and no one else is ever charged with the crime. Such a case marks a failure by law enforcement. Either a guilty person was somehow acquitted, or the real perpetrator of the crime has not been found. In either event, the person who committed the crime goes free. It is this controversial result that marked the conclusion of what became known nationwide as “The Girl Scout Murders.”

Hart was a primary suspect from the beginning of the investigation. He was an escaped convict and grew up in the area where the crimes occurred. He was also a Cherokee Indian, and the author describes how that fact played into the mix. The trial began on March 5, 1979, and jury deliberations began at noon on March 29. By 10 a.m. the next day, the jury had reached a unanimous verdict of not guilty. On June 4, 1979, Hart died of a heart attack while in prison for earlier offenses.

If Hart was guilty, very clearly the state — investigators, local sheriff, OSBI, and lawyers, had not done their collective job. The author notes, at page 146:

Later, jurors would say they had believed there was “manufactured evidence” and that “the investigation was a screwed-up mess.”

Although the science of DNA testing did not exist at the time of the Hart trial, three post-trial attempts to determine DNA matching, in 1989 or so, 2002, and 2008, were inconclusive.

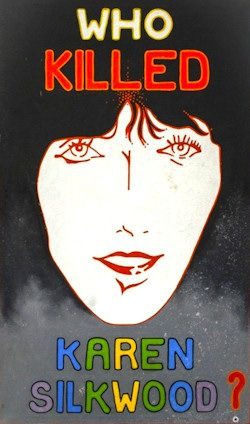

Case #4 — The Karen Silkwood Case, Chapters 38-49.

Case #4 — The Karen Silkwood Case, Chapters 38-49.

Unlikely Adversaries, The Union, Contamination, The Fatal Accident, Accident Reconstruction, Headlines, The AEC, The FBI, & Congress, Silkwood v. Kerr-McGee, The Trial, The Plaintiff’s Case, The Defense, Appeal, Reversal, & Settlement

This is the only case presented in Notorious that did not involve a criminal trial — but it did involve a high profile civil suit brought by the surviving members of Silkwood’s family against Kerr-McGee, the then mainstay energy company in Oklahoma. It was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma on the grounds of negligence — gross and ordinary — and strict liability in tort due to an allegedly inherently dangerous substance — plutonium.

Inexplicably, Kerr-McGee denied that plutonium was an inherently dangerous substance and its denial opened the door for the plaintiffs to offer evidence that — duh — plutonium was an inherently dangerous substance and to prompt the plaintiffs’ often-mentioned mantra during trial that, “If the lion gets away, Kerr-McGee must pay.”

Inexplicably, Kerr-McGee denied that plutonium was an inherently dangerous substance and its denial opened the door for the plaintiffs to offer evidence that — duh — plutonium was an inherently dangerous substance and to prompt the plaintiffs’ often-mentioned mantra during trial that, “If the lion gets away, Kerr-McGee must pay.”

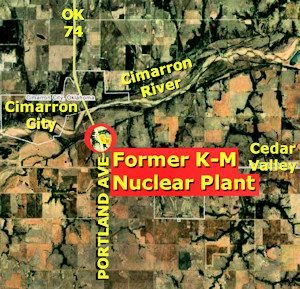

Karen Gay Silkwood was born February 19, 1946, in Longview, Texas, and died on November 13, 1974, along OK 74 located south of the Cimarron River and of Crescent, and north of Oklahoma City on the same road which becomes Portland Avenue and the Lake Hefner Parkway in Oklahoma City.

Shortly before and certainly after her death, Silkwood became a cause célèbre for labor, women’s rights, and anti-nuclear movements. The events even spawned a fine movie, Silkwood, a Mike Nichols film starring Meryl Streep as Silkwood, Kurt Russell, and Cher. Notwithstanding how public perception may have come to view and/or mold her legacy, she was not opposed to the nuclear energy industry in the United States, but she was concerned about labor and safety issues. Silkwood’s job at the Cimarron plant was to create plutonium pellets and load those pellets into long, stainless steel rods, and no information is presented indicating that she had any objection to those assignments.

How and/or why did she die? Was it because she was a whistle-blower concerning Kerr-McGee’s safety practices? Ultimately, the question became, what was Kerr-McGee’s culpability in causing her death?

On November 13, Silkwood drove from the Kerr-McGee plant southbound on OK 74 toward Oklahoma City when her car veered off the road and crashed, the crash causing her death. It was said that she was on her way to a meeting with a reporter for the New York Times and was carrying evidentiary documents harmful to Kerr-McGee. Those documents, if any there were, were never to be found.

Some surmised that her vehicle struck was from the rear, forcing her car to careen off the road — one accident reconstruction expert surmised that the scenario was at least possible or even likely. Or was she under the influence of drugs or otherwise fell asleep, causing her own death? Was the plutonium contamination found in her residence placed there by Silkwood or planted there by Kerr-McGee?

The federal court litigation had high-powered lawyers all around and Kent explores them all very nicely. Without getting into much detail here, the case went to the jury and it returned a verdict for $5,000 property damage, $500,000 for personal injuries, and $10,000,000 for punitive damages. Very evidently, the jury bought the substance of the plaintiffs’ case. But, on appeal, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals determined that the issue of personal injuries should have been pursued in Oklahoma Worker’s Compensation Court and the personal injuries award was vacated as was the $10,000,000 punitive damage award — only the $5,000 property damage award was affirmed. The U.S. Supreme Court accepted further review, and it determined that the 10th Circuit was wrong in vacating the punitive damage claim and the issue was remanded (sent back) to the 10th Circuit, which, in turn, sent the matter back to the trial court for retrial, five years after the original verdict.

Rather than undergo another expensive and lengthy trial, in August 1986, the parties reached a compromise and Kerr-McGee agreed to pay $1,380,000 for a settlement of all claims.

Even today, this being the 40th anniversary of Silkwood’s death, her case is the subject of retrospective analysis and controversy. As examples, see the October 28, 2014, issue of County Line Magazine, and the November 10, 2014, issue of The Tulsa World.

Case #5 — The Sirloin Stockade Murders, Chapters 50 – 61.

The Crime, The Investigation Begins, The Lorenz Case, The Guns, Getting a Break, Roger Dale Stafford, Lawyered Up, The Trial, Roger Dale Takes the Stand, The Death Penalty, The Lorenz Trial, Verna

On Sunday night, July 16, 1978, the bodies of six employees at the Sirloin Stockade restaurant, 1620 S.W. 74th Street, Oklahoma City, were discovered in the restaurant’s small walk-in freezer, all shot. All but one was dead and she died later that evening. They were Terri Horst (age 15), David Salsman (15), David Lindsey (17), Anthony Tew (17), Isaac Freeman (56), and Louis Zacarias (43). Almost a month earlier, on June 22, 1978, a passing motorist discovered the bodies of Air Force Sgt. Melvin Lorenz (38) and his wife, Staff Sgt. Linda Lorenz (34). The body of their twelve-year old son, Richard, was found the next day. All had been shot dead about two miles south of Purcell, Oklahoma, near the northbound lanes of Interstate 35. While driving from San Antonio to Fargo, North Dakota, to attend Melvin’s mother’s funeral, they stopped to offer assistance to motorists whose car was apparently disabled, but instead of helping the stranded motorists, they were murdered by them.

In all these murders, the same people, Roger Dale Stafford, his wife Verna, and his brother, Harold, were the killers, but that was anything but evident at the outset. Early on, linkage between the pair of killings was not evident, and the identity of the killers was a mystery without leads.

If the Girl Scout Murders case serves to illustrate poor police work and prosecution, this pair of group homicides represents the other side of the coin. As to the Sirloin Stockade case, the author says,

No rational motive existed for the killings, and no obvious suspects could be identified. Solving the murders had to be accomplished the old fashioned way, by intense and thorough police work. The officers involved deserve credit for cracking the case, though the big break came compliments of the bizarre personality of the killer, Roger Dale Stafford.

Stafford’s brother, Harold, died in a motorcycle accident six days after the Oklahoma City killings; after all his appeals failed, Roger Dale died on July 1, 1995, by lethal injection in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester, Oklahoma; and Verna is living in the Mabel Bassett Correctional Center in McLoud while serving the early part of her eventual sentence — two consecutive life terms.

A subchapter title in this case might have been Verna Rae Stafford vs. Roger Dale Stafford, husband and wife. Roger had apparently counted on her not being able to testify against him, but a change in Oklahoma law was interpreted by the courts as allowing her testimony.

A subchapter title in this case might have been Verna Rae Stafford vs. Roger Dale Stafford, husband and wife. Roger had apparently counted on her not being able to testify against him, but a change in Oklahoma law was interpreted by the courts as allowing her testimony.

The author reports on Roger Dale being interviewed/questioned by Arthur Linville, OSBI agent, as follows:

The author reports on Roger Dale being interviewed/questioned by Arthur Linville, OSBI agent, as follows:

When Linville advised Roger Dale that she [Verna] could indeed testify against him, Roger Dale was visibly shaken.

“Man, I can’t think. I’ve got to think. All I can see is the gas chamber,” he said.

Verna’s cooperation with the prosecution doubtless facilitated the state’s case, even though much other evidence was presented at Roger Dale’s trials other than his wife’s testimony — not the least of which was Roger Dale’s own testimony. He evidently considered himself as possessing an unerring ability to talk himself out of anything and he apparently insisted on waiving his right against self-incrimination and testifying to the juries in both the Sirloin Stockade and Lorenz murder trials. That didn’t work out — he received six death sentences in the Oklahoma City and three in the Purcell trials.

Doubtless, Verna hoped for leniency when her own participation in the murders was decided, following Roger Dale’s death sentences. Initially, in a plea agreement between the prosecutors in both cases and her attorney, she received an indeterminate sentence of 10 years to life. However, the author states at page 249:

In an unrelated case, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals had ruled that a court could not set an indeterminate sentence in a case in which a life sentence was the maximum imposed. Based on this decision, Verna moved to set aside her sentence and be resentenced to ten years which, given time served, would have allowed her to go free immediately.

Her resentencing hearing was assigned to Oklahoma County District Judge Richard Freeman. The judge correctly set aside Verna’s original sentence but then proceeded to conduct a hearing in which both parties offered evidence.

* * *

At the close of the evidence, Judge Richard Freeman hammered Verna with two life sentences to be served consecutively, effectively meaning she would have to be paroled twice to ever have a chance to get out of prison. Judge Freeman told Verna, “I would wager that there’s one of the hottest corners of hell vacant with your name right above it.”

The author spins the true tale of these two groups of grizzly murders, step by step, inch by inch, in a darkly fascinating and unfolding drama. Any number of interesting items could be mentioned, e.g., Roger Dale’s Oklahoma City trial was the first trial in Oklahoma to be broadcast on television.

The above killings were the worst to occur on Oklahoma soil, but that would change on April 19, 1995.

Case #6 — The Oklahoma City Bombing, Chapters 62-79.

Where Were You, McVeigh & Nichols, Waco, The Plot, Leaving a Trail, Building the Bomb, The Crime, The Arrest, The Investigation, The Arrest of Nichols, McVeigh’s Lawyer, The Legal Battle Begins, The Trial, The Defense, The Case Against Nichols, Nichols’s Defense, State of Oklahoma v. Nichols, Conspiracy Theories

Candidly, this is one case about which I did not want to read. I can answer the question, “Where Were You,” posed by the author’s first sub-chapter in this case. . I can answer the question, “Where Were You,” posed by the author’s first sub-chapter in this case. I was downtown in the first floor of the Oklahoma County Courthouse on Friday, April 19, 1995, at 9:02 a.m., sitting in the jury box of Judge Clinton Dennis’s courtroom as he was beginning to call his regular Friday morning motion docket. Rather than elaborate on my personal experience further, allow me to say that the cases of the Murrah Bombing, Timothy McVeigh, Terry Nichols, the 168 murdered victims, including 19 babies and older children, and another 680 who were injured, and the trauma that all Oklahoma Citians suffered and endure through this day, are not things that I willingly recall, even now, almost 20 years later. I’ve never written on the topics in Doug Dawgz Blog, and, aside from these brief paragraphs, I never will.

Gladly, the author’s “just the facts, ma’am,” approach keeps a reading of this case from becoming teary, and that method pleased me greatly. A very tough and sensitive subject was handled brilliantly, and that’s all I have to say about that.

Mastery of Content. Notwithstanding my mild criticism of his Notes section, below, Mr. Frates’s research and command of the subject matter of his book are plainly evident. Meticulously, he pieces together each facet of the six cases with amazing ease — a task which could not be done without a deservedly confident knowledge that he had done his research well and thoroughly. The Notes section reflects his review of media reports, trial transcripts, appellate case decisions, interviews with defense and prosecuting attorneys, and more. In the Machine Gun Kelly & Urschel Kidnapping case, he even relates conversations with Charles Urschel, the man kidnapped who also happens to be the author’s uncle.

Writing Approach and Style. In describing how he formed the book’s title, Kent says, “For a lawyer, a straightforward statement is usually the best way to communicate,” adding, “That’s not necessarily true for writer of history.” Although I am uncertain about how he would differentiate between the two, his use of simple words, short sentences, short paragraphs and chapters, and straightforward language in fitting together the often-complicated pieces of each of the six cases’ puzzles results in an exceptionally easy to read masterpiece of story telling. By comparison, not one of his sentences are as complicated as the compound sentence I’ve just written. Not once did I need to re-read a sentence to understand what the author just said.

Each of the six cases in Notorious are broken into a varying number of context-driven chapters for each of the six cases. By “context-driven,” I mean “subtopic” — e.g., in the Machine Gun Kelly & The Urschel Kidnapping case, the chapters are “The Kidnapping,” “Not Your Normal Hostage,” “The FBI,” “The Ransom,” “The Hunt,” “On the Run,” “The First Trial,” “Aftermath,” and “Kathryn & Ora Set Free.” One might say that each chapter represents one large piece in the overall legal puzzle. By the use of such chapter subtopics, a reader understands what piece of the puzzle is being described and no need exists to have a strictly lineal timeline since multiple pieces of the puzzle may well be occurring simultaneously — much like a modern-day movie would do.

The chapters are short, ranging from three to eight pages with three-to-four pages being the norm. Coupled with what I already said — that sentences are short and easy to read — each case story flows easily and quickly and, before you know it, the book is done.

In addition to his content mastery, Mr. Frates’s writing style garners my highest compliments. It is no small task to take a complex case, regurgitate it, and then parcel it into coherent, brief, and easy-to-read subtopic-chapters — and do that six times — a task which the author brilliantly accomplishes.

Criticisms. I have just a few …

No Index. Academically, I criticize any history book that does not contain an index at its end — maybe that’s just me or my view of good scholarship. Even though I’m hard-pressed to see how an index would add a great deal that the book’s very descriptive table of contents fails to provide, still, I note that Notorious contains no index.

The Notes. As a reader of history, I like specific endnotes or footnotes within the text as the author tells his/her story. That way, I can follow up to the referenced note and check out the source and/or read more from that identified source than the author provided, if I want. Although an 11-page Notes section does exist at the end of Notorious and is fairly extensive, my preference is that actual endnote numbers be used within the text of the book which link to particular notes identified in the closing Notes section.

Moreover, in the Notes section, the word “chapter” is used to refer to a particular case, e.g., “Chapter 2, The United States of America v. David Hall,” as opposed to the “chapter” usage which appears in the book’s body which range from chapter 1 through chapter 79. In this example, the David Hall case was identified as chapters 12 through 24 which are collectively identified as “Chapter 2” in the Notes section.

Last, on occasion, the Notes section is date specific, sometimes not — e.g., referencing the David Hall case, the author notes that personal interviews occurred with three individuals by name and date, but sometimes other sources are not as particularly identified, such as when referencing “Newspapers” — the names of the newspapers (Oklahoma City Times, The Oklahoman, San Diego Union, Tulsa World) are mentioned but no particular articles are identified by byline or by date or in what context and/or literal chapter they might relate to. In the David Hall case, literal chapter numbers are from chapter 12 through chapter 24 — but the Notes section is unspecific in such regards.

Summary. This is one of the most thorough, easy to read, substantive, and, yes, finest books on Oklahoma (and Oklahoma City) history that I’ve had the pleasure to read. It is also inexpensive. Its content is well-chosen. It is easy to read. The book production quality is excellent in all respects. Only in its lack of an index, and footnotes or endnotes within the text, coupled with more particular note identification in the book’s Notes section, does any shortcoming exist. In balance, these criticisms are not sufficient to cause me to lower my esteem for this book from 5-stars, my highest rating, to any lower number. Notorious is a 5-star book. It is a must buy for any lover of Oklahoma City, as well as Oklahoma’s, history.

The Book’s Website: http://www.okmostnotoriouscases.com/

Full Circle Purchase: Click here Amazon description/purchase: Click here

The author’s biography: click here