This is a test question: The first “legal” settlers in Oklahoma City acquired their rights on:

(1) April 22, 1889, Land Run

(2) Earlier than the Land Run

If you chose (1), amazingly, you may well be mistaken; if you chose (2), you are just as amazingly, but more likely than not, correct.

How can the second choice possibly be correct? Most if not all established historians and other writers take it as a given that land in the Unassigned Lands could not be legally acquired prior to the April 22, 1889, Land Run. Boomers couldn’t; Sooners couldn’t. The notion is so ingrained that it is almost universally assumed to be a “given,” something beyond dispute, beyond being questioned.

But are legitimate Land Runners really all there were in the context of legitimate claim holders to that part of the Unassigned Lands which today comprise a part of Oklahoma City?

Not necessarily. There were arguably if not most likely a handful of black freedman who settled in Oklahoma City south of Reno, east of May, in 1884, in part of the area that became known as “Sandtown,” more particularly in the Sandtown area that I’ll call “the boot,” in the bend of the North Canadian River which is more or less in the Lewis Addition to Oklahoma City, described below.

The fact that the Sandtown area was a black neighborhood in Oklahoma City in early Oklahoma City annals is not disputed by anyone. But, the issue of how and when those black residents came to be there in the first place has not been investigated by any Oklahoma City historian, save one, Ronald James Webb.

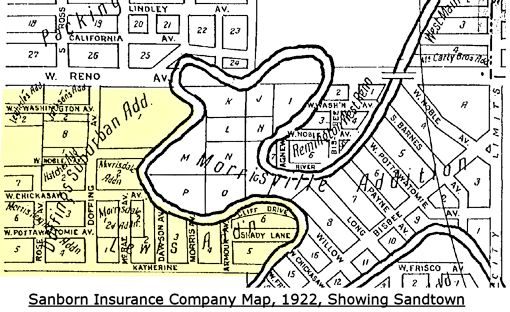

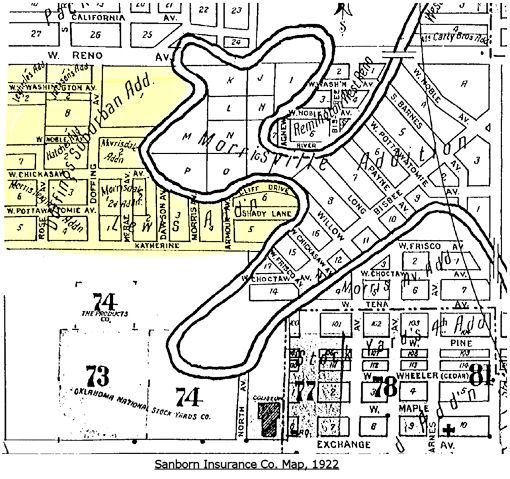

Sanborn Ins. Co. 1922 Map Showing The Sandtown Area

INTRODUCTION. The “Five Civilized Tribes” residing in Indian Territory before the Civil War owned African American slaves, but after the Civil War they were freed, hence their name, “freedmen.” This article develops the notion that some of them came to reside in the Sandtown area in 1884, five years before the April 22, 1889, Land Run, and that they continued to reside there from that time for as long as the Sandtown community continued to exist. As well, it provides as much information about their community, life, and environment as I’m able to tell.

In a September 29, 1997, Oklahoman article by Melissa Nelson, “Memories Help Sandtown Area Come Alive,” she wrote:

William Welge, the Oklahoma Historical Society’s archive director, said his organization has no records on Sandtown’s history. ¶ Welge said he doubts the claim by Antioch Baptist Church at 2727 SW 3 that it was founded in 1885. That was before the unassigned lands were opened to public settlement. ¶ But Welge said former slaves known as freedmen could have settled the area under a federal program to relocate southern blacks. ¶ “It’s unfortunate that the Sandtown area is largely forgotten and has been totally ignored by historians,” he said. “Really, there are only a handful of people who [illegible] it ever existed.”

Are the claims of these freedmen and their descendants imaginary, as OHS historian Bill Welge suggested, or are they real? If real, the written history of the origins of Oklahoma City requires a rewriting so that written history matches factual reality. In addition to tracing the history of Sandtown, this article explores the possibility that, like Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Invisible Man, these black men and women who collectively comprised “Sandtown” did exist even if they have been invisible in Oklahoma City’s written history.

PART 1: THE RESEARCH AND WRITING OF RONALD JAMES WEBB. While doing my research on Oklahoma City’s Sandtown, one of the links I followed was to www.sandtownhistory.com (which doesn’t appear to be working as I write this text). In that website, a link was present to “History of Sandtown,” or something like that. When I clicked the link, the referenced internet page was no longer available. But I also found an email address for Mr. Webb and I began an e-mail discussion with him which turned out to provide a treasure trove of information … a godsend, actually.

PART 1: THE RESEARCH AND WRITING OF RONALD JAMES WEBB. While doing my research on Oklahoma City’s Sandtown, one of the links I followed was to www.sandtownhistory.com (which doesn’t appear to be working as I write this text). In that website, a link was present to “History of Sandtown,” or something like that. When I clicked the link, the referenced internet page was no longer available. But I also found an email address for Mr. Webb and I began an e-mail discussion with him which turned out to provide a treasure trove of information … a godsend, actually.

Due to his host’s web page formatting issues, he explained, the paper that he’d written in 2005 was no longer available on that website … but, he asked me if I would like to have a copy.

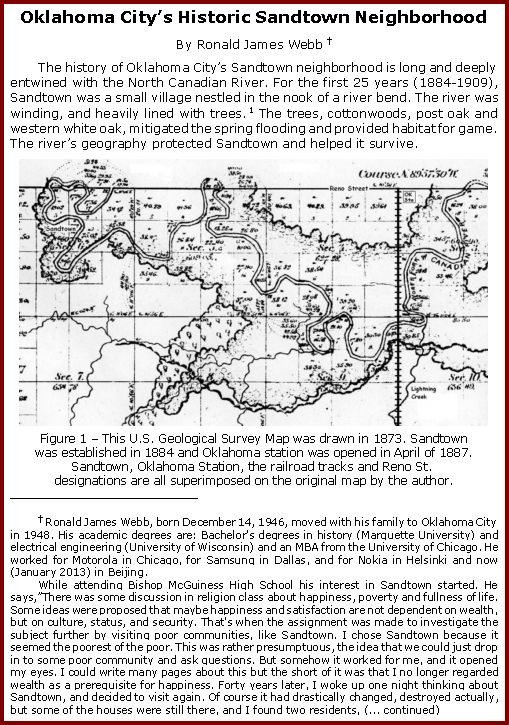

Would I like to have a copy? Hoorah! Cha-ching! “Are you kidding?” I replied. Of course I would. To shorten the story a bit, he furnished me a copy of his paper in Microsoft Word format; I converted it to WordPerfect format (the word processing software that I use); I then created a PDF version of his paper, complete with bookmarks. He kindly allowed that I re-publish his paper here. Aside from formatting changes, the only difference between his 2005 research paper and the 2013 re-publication here is that I have added a footnote which gives his own background information and describes how he became interested in Sandtown, as follows:

| Ronald James Webb, born December 14, 1946, moved with his family to Oklahoma City in 1948. His academic degrees are: Bachelor’s degrees in history (Marquette University) and electrical engineering (University of Wisconsin) and an MBA from the University of Chicago. He worked for Motorola in Chicago, for Samsung in Dallas, and for Nokia in Helsinki and now (January 2013) in Beijing.

While attending Bishop McGuiness High School his interest in Sandtown started. He says,”There was some discussion in religion class about happiness, poverty and fullness of life. Some ideas were proposed that maybe happiness and satisfaction are not dependent on wealth, but on culture, status, and security. That’s when the assignment was made to investigate the subject further by visiting poor communities, like Sandtown. I chose Sandtown because it seemed the poorest of the poor. This was rather presumptuous, the idea that we could just drop in to some poor community and ask questions. But somehow it worked for me, and it opened my eyes. I could write many pages about this but the short of it was that I no longer regarded wealth as a prerequisite for happiness. Forty years later, I woke up one night thinking about Sandtown, and decided to visit again. Of course it had drastically changed, destroyed actually, but some of the houses were still there, and I found two residents, Glennie Hunter and Lucile Williams, who had been born and raised in Sandtown, I mention these in the article. Glennie Hunter was the most valuable source of information, she provided many photos, stories and a fairly complete history of Sandtown. I was hooked. I then made a systematic study of Sandtown, starting with the Antioch Baptist Church, which had been located in Sandtown from 1884 until 1999, according to their records. I spent hours at the OHS, with help from a friendly worker there. Consulted old newspapers, Polk City Directories, Sanborn maps and census data. I spent hours at the land and tax offices researching warranty deeds starting with April 22, 1889. I read several books about OKC, including McRill’s classic And Satan Came Also, and Stan Hoig’s The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889. McRill was involved personally with Sandtown, and Hoig provides excellent detailed information about what happened around OKC in the 1880’s before the Land Rush. I found a monograph about Sandtown culture, written by Phelicia Ann Morton, a Sandtown resident who went to Cornell University, graduated and got a Master’s degree there. In short, it became a passion for me, culminating in this article.” “I sent the article to the OHS. After several months without response I inquired again, did they receive it? Again, no response. So after six months, I created a website www.sandtownhistory.com, and published an abbreviated, but more decorative version, online. I then was contacted by the head of the OHS who said that she just started in the job, and found my manuscript in an old shoebox. I told her that I had already published the article on my website, and she said that it was regrettable, but the OHS cannot publish anything that has been published already elsewhere.” As noted above, Mr. Webb’s article was originally self-published in 2005. This republication is made in January 2013, with only formatting changes to the original. |

Mr. Webb’s 25-page single-spaced article includes 14 images and 54 endnotes which identify his sources. In addition to establishing a legitimate basis for the claim that Sandtown’s origins trace to 1884 and continued thereafter, his article contains information about the people, community, culture, and environment in and around Sandtown, much of that based upon interviews with Sandtown residents in 2005. The paper is seriously researched and is written by the pen of a scholarly author, one not to be taken lightly. We are all indebted to Mr. Webb for allowing his paper to be available here, for all to read.

Click here or click the image below to open and/or save to your computer Ronald James Webb’s “Oklahoma City’s Historic Sandtown Neighborhood.”

The author describes Sandtown before and after the passing of Jim Crow ordinances in Oklahoma City which established residential white and black “blocks,” and he explores the impact of the Packingtown district in and after 1906 upon Sandtown residents. Churches, schools, business, and other activities are discussed, as are the environs around Sandtown itself, including conflict with the antagonistic residents of nearby Mulligan Flats. At page 17, this description of Sandtown is presented:

In the 1940’s and 50’s Sandtown hosted weekly block parties between Chickasaw and Pottawatomie (3rd and 4th) Streets on Doffing Ave. Maddie Wright, on the piano, and her husband George on the guitar, got things started on Friday nights. The parties often extended through the weekend. Glennie recalls that “there was never trouble except when Eastsiders came over.” The Sandtown community was stable and close-knit. “People looked out for each other and the town was like a big family.”

Something about living on the river, the uncertainty and the possibility of imminent disaster, gave the citizens an edgy lust for life that is found today only in places like New Orleans and San Francisco. On the other hand, Sandtown was very stable. People moved into Sandtown and stayed, at least until the packing plants closed.

Of course, the North Canadian River is also described — as the source of both early day sustenance and the devastation caused by occasional flooding. River straightening from 1953 to 1958, construction of the I-40 crosstown expressway in the mid-1960s which split Sandtown apart, and the closing of the meat packing companies from 1960 through 1981, all contributed to the demise of this first and most historic neighborhood of Oklahoma City.

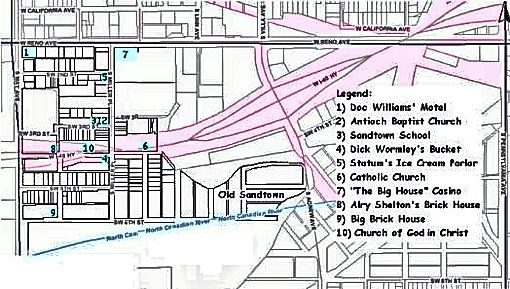

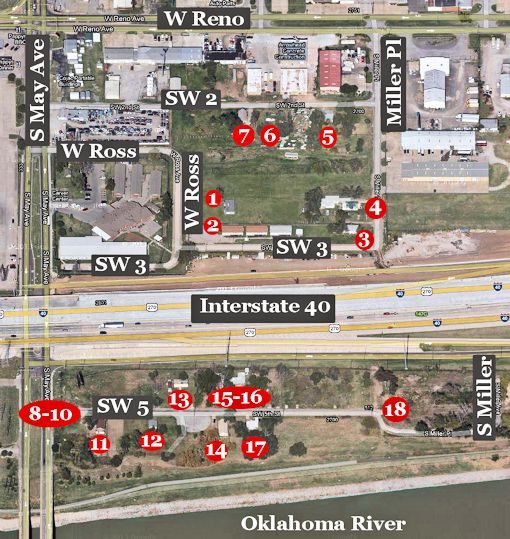

The last image in Mr. Webb’s article portrays Sandtown over time … after the I-40 crosstown was built and which split the region, and after the relocation of the North Canadian River, and it provides an index locating some of Sandtown’s once-existing structures.

Thanks, Ronald James Webb, for allowing that this outstanding piece of work be made available here and for your contribution to Oklahoma City history.

PART 2: MY OWN RESEARCH. First, some definitions and clarifications are in order. Although sometimes reported as “Sand Town” in the Oklahoman, the correct name for the black community south of Reno, east of May Avenue, north of Packingtown (more particularly, north of Katherine Street [SW 6th Street]), and west of Agnew (broadly defined — Sandtown was not as far east as Agnew; the old riverbed of the North Canadian River was Sandtown’s eastern border) is “Sandtown,” one word. Secondly, Sandtown is not at all the same as the the Walnut Grove area south of Bricktowown or the “May’s Camps”, also called “Community Camps” or “Hoovervile Camps” which existed during the Great Depression, nor is it the same thing as “Mulligan Flats,” the latter area being mentioned in Mr. Webb’s article.

Last, it may be that a totally different area known as “Sand Town” existed near the North Canadian River south of the warehouse district that is known as Bricktown today, perhaps what Dr. Blackburn had in mind for the Walnut Grove area which he labeled “Sand Town.” In this post on Deep Deuce history, I reported that our renowned Oklahoma historian Bob Blackburn said,

From 1889 to the 1930s Bricktown was a battleground for social justice and the birthplace of cultural diversity in Oklahoma City.

It began when some of the first 200 African-Americans attracted by the land run settled in Sandtown, located along the north bank of the river east of the Santa Fe tracks. From there, the black community grew northward as jobs were created and new waves of immigrants arrived looking for a piece of the promised land.

STOP, already. If an area did exist where Dr. Blackburn said, known as “Sandtown” or as otherwise reported “Sand Town,”, it was NOT the more historic area more properly known as “Sandtown,” south of Reno, east of May Avenue, about three miles west of the Santa Fe railroad tracks, that arguably if not most probably existed in 1884. The settlers in the “real” Sandtown almost certainly appeared in their chosen area five years before the 1889 Land Run, or, at least, I am so persuaded. No disrespect at all is intended to Dr. Blackburn in saying this … instead, I am reminded of the words of William Welge, mentioned at the outset of this article,

William Welge, the Oklahoma Historical Society’s archive director, said his organization has no records on Sandtown’s history. * * * “It’s unfortunate that the Sandtown area is largely forgotten and has been totally ignored by historians,” he said. “Really, there are only a handful of people who [illegible] it ever existed.”

Déjà vu, ala Ralph Waldo Ellison’s, The Invisible Man. “The Sandtown area is largely forgotten and has been totally ignored by historians.” Enough said.

Second, let’s have a look at a few maps showing the Sandtown area.

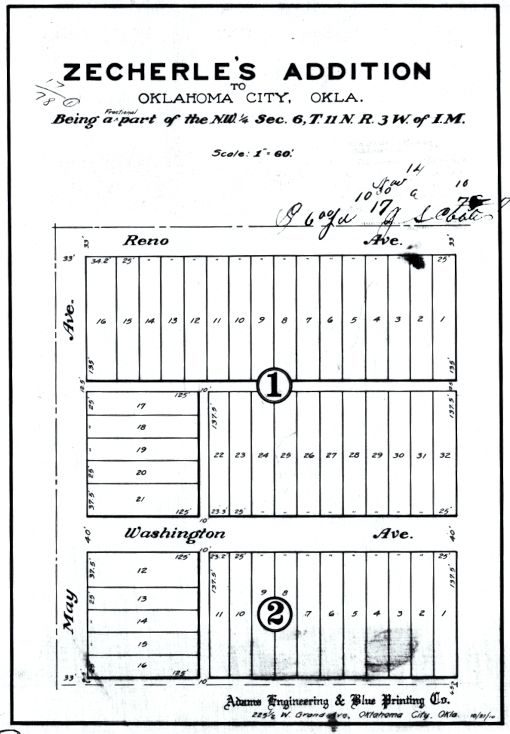

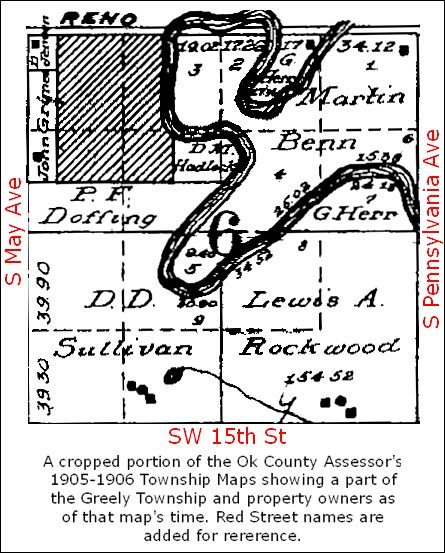

County Assessor’s 1905-06 Township Plats. Probably the earliest map available is a crop from the 1905-06 Oklahoma County Township Maps showing part of Greely Township, more particularly, Section 6, Township 11 North, Range 3 West of the Indian Meridian, Oklahoma County, Oklahoma:

Mr. Webb’s article includes this map and discusses early real property transactions involved with early-day Sandtown real property transfers. Particularly, he notes that the small area at the river’s bend owned by D.M. Hadlock was acquired by him in January 1906 and was the “original” or “old” Sandtown before its expansion west toward May Avenue and north toward Reno.

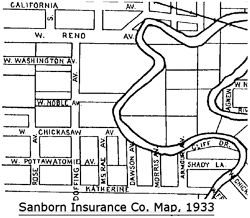

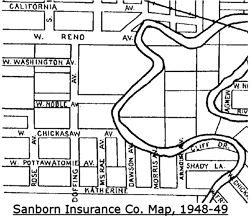

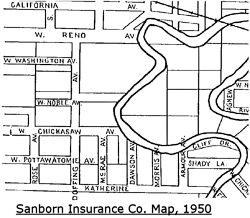

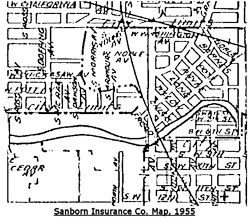

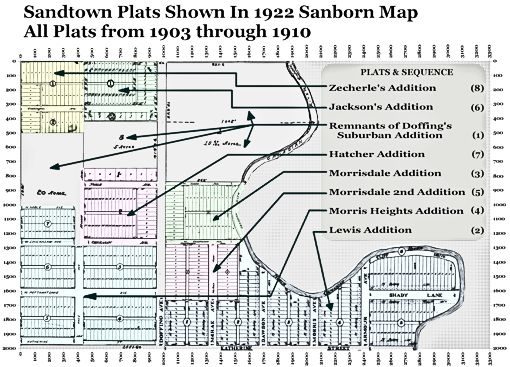

Sanborn Insurance Co. Maps. Sanborn Insurance Company maps between 1922 and 1955 show the Sandtown area in “Index” maps but none of those Sanborn maps present detailed maps of the area as was generally done with other areas within the boundaries of Oklahoma City. Nonetheless, the index maps are useful. Click on map images for larger views.

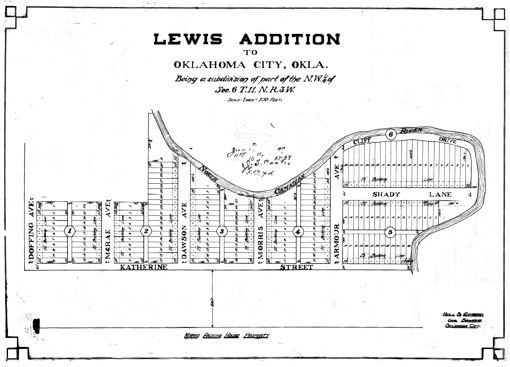

Beginning with the 1922 Sanborn map, the Sandtown area is shown with various street names and those street names remained constant through the 1950 map. About that, Mr. Webb says, in his article when describing Figure 6, “The streets of Old Sandtown were never named. Cliff Drive and Shady Lane appear on maps from the 1920’s perhaps as a mapmaker’s joke.” With respect to Mr. Webb, Cliff Drive and Shady Lane are present in the Lewis Addition plat, presented shortly, and from which the Sanborn Maps assuredly derived their names. After the filing of the Lewis Addition plat in June 1909, those names were plainly official, even if they may not have been used by Sandtown residents.

The 1955 Sanborn map image, above, is the poorest quality of any other Sanborn map images. Nonetheless, it does show the change in the North Canadian River that had occurred by that time.

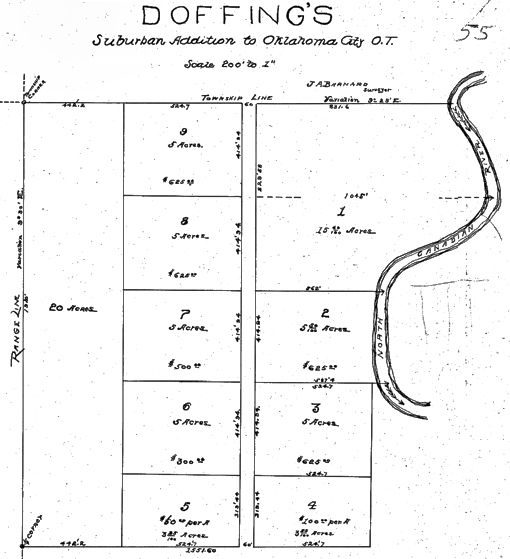

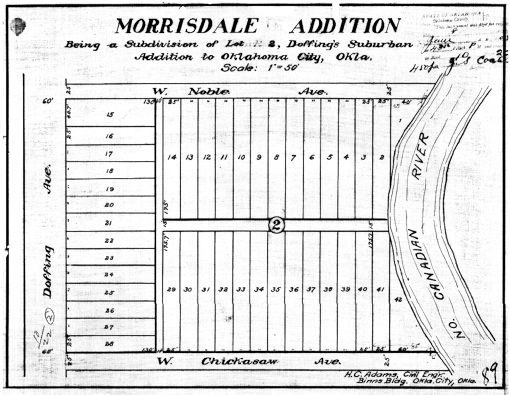

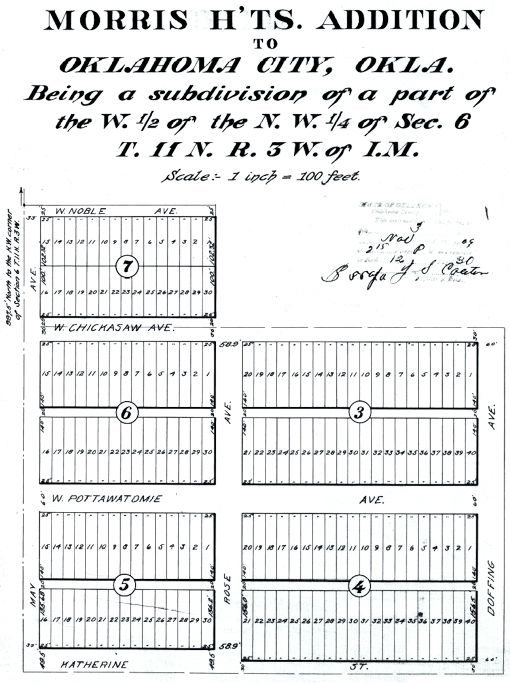

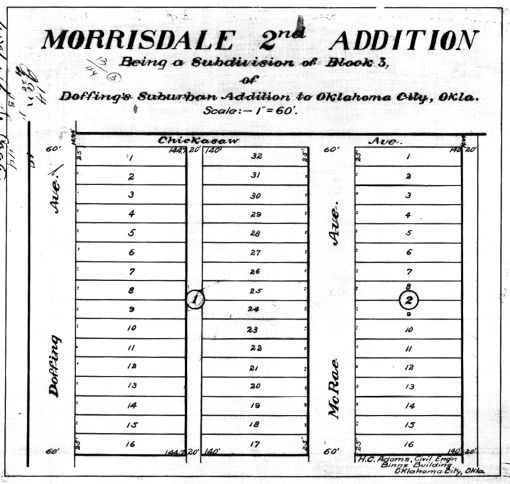

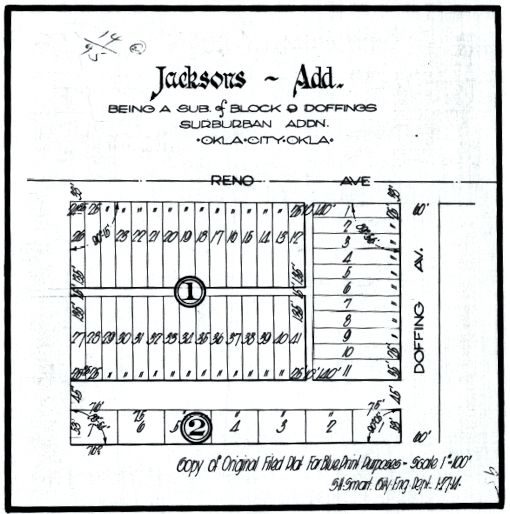

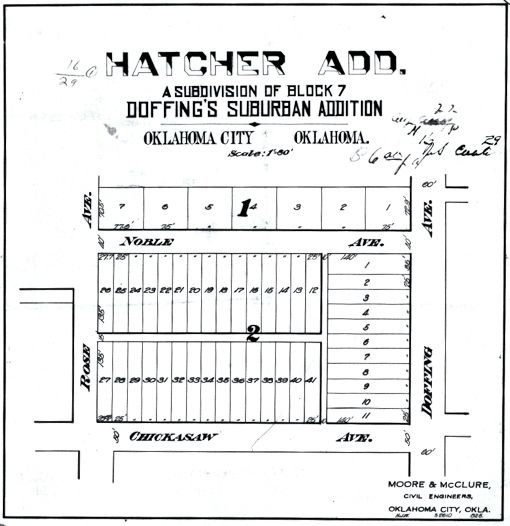

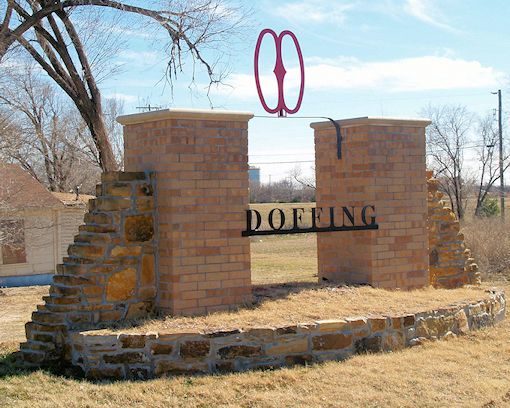

Plats. As of the 1922 Sanborn map, eight plats were filed for record embracing all of Sandtown from 1903 through 1910. The first, and from which the Doffing Neighborhood organization takes its name, is Doffing’s Suburban Addition, filed November 18, 1903. Aside from Lewis Addition, it embraced all areas in Sandtown from Reno to Katherine (SW 6) and from May Avenue east to the North Canadian River, many of which areas would be further subdivided during 1909-1910. It did not include the “original” Sandtown area represented by most of the Lewis Addition plat, reminiscent of a boot. All plats are shown below.

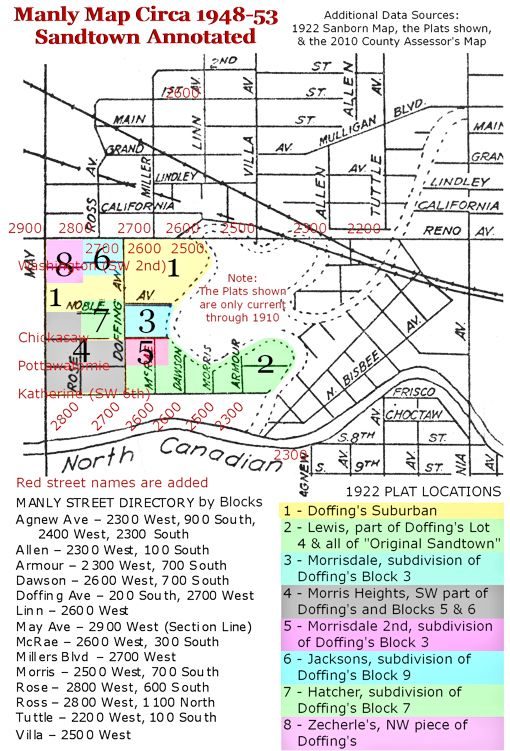

How It All Fits Together. I’ve assembled a Sandtown map which fits all of the above plats into a single image and in which the Sandtown puzzle-pieces are made clear. The map is scaled and the scaled measurements fit the specific and general regions of Sandtown. To see a high resolution image of this map, click here. To see a 1024 px wide image of the map, click the map, below.

Other plats or modifications to existing plats doubtless occurred after 1910 but I’ve not explored such possible changes, my intent here being to focus on Sandtown as it existed in its earliest days.

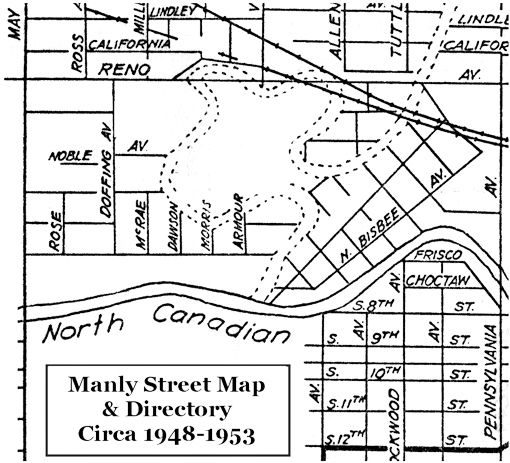

Manly Office Supply Map. Manly Office Supply Company was a long-existing office supply company located downtown in the First National Center. It produced a map of Oklahoma City which appears to span the 1930s and 1940s, perhaps even into the early 1950s, with updates over time. Unfortunately, the map is not dated. I had thought that the copy that I own was published around 1947-1948, but, given that the North Canadian River’s location is shown as changed or changing in this map, it may be that this map was published around 1953. Regardless, the map shows the Sandtown area as follows:

The Manly Map is also helpful in getting a fix on particular street locations since it includes a street index. In the expanded, annotated Manly map view below, note that blocks north of Reno had a different numbering system than blocks south of Reno and that they are “skewed.” For example, “the Big House casino” mentioned in Mr. Webb’s article shows the property located on Reno in the north part of Sandtown. However, the 2500 block on the north side of Reno would locate that property at Villa and Reno, different than Mr. Webb’s map. BUT, adjusting block numbers south of Reno for those shown in the Manly Map places the Big House casino just as located in Ron’s map.

An expanded and annotated view of the Manly Map is shown below. Manly’s Map doesn’t include all Sandtown street names but they have been added, largely based upon locations identified in the 2010 County Assessor’s aerial map, shown shortly. The annotated map also identifies the plats shown in the 1922 Sanborn Map, they being added from 1903 through 1910. Doffing’s Suburban Addition (1903) included most of Sandtown, but it did not include the “Original Sandtown” area shown at the river bend, lower right, which was platted as Lewis Addition in 1909. Other plats may have been filed after 1910. The remnant of the original Doffing’s Surbaban Addition after the subsequent plats is shown in yellow.

Sandtown In 2013. The Google Map below shows what’s left of Sandtown as this article is written. Basically, a slice exists north of Interstate 40, along SW 3rd and thereabouts, and south of Interstate 40, along SW 5th Street. Sandtown’s former southern border, SW 6th Street (earlier named Katherine), mostly lies at the bottom of the Oklahoma River.

Contemporary Images. On February 4, 2013, I drove through the areas shown in the above map and took some photos. Some items didn’t occur to me to take, but I’ve assuaged my neglect by using images from Google Maps street view. An index of the photographs appears below:

The numbers in the map correspond with the following pictures. It will be obvious that some images are not historic Sandtown structures but I’ve included the more contemporary buildings for completeness. The thumbnail images shown below are cropped and reduced in size from the larger (1024 px wide) images. Click on any thumbnail to see its larger image.

| Buildings North of Interstate 40 | |

1 – Near W Ross |

2 – On SW 3rd |

3 – Corner of SW 3 & Miller Pl |

4 – On S Miller Pl |

5 – On SW 2nd |

6 – On SW 2nd |

7 – On SW 2nd |

|

| Buildings South of Interstate 40 | |

8 – SW 5th From May Ave |

10 – Adopt A Street Sign |

9 – Neighborhood Association Gateway MarkerIn 2006, under the leadership of Dana Lusk Dunn, the Doffing Neighborhood Association was formed. It chose the name Doffing instead of Sandtown, but the association’s intent is to embrace the historic Sandtown neighborhood, most of the remnants being on SW 5th Street. In 2007, the association received a $10,000 grant from Oklahoma City to construct this “gateway” edifice on SW 5th Street, on the east side of May Avenue. |

|

11 – On SW 5th |

12 – On SW 5th |

13 – On SW 5th I’m showing a larger thumbnail for this image since it was one |

|

14 – On SW 5th |

15 – On SW 5th |

16 – On SW 5th |

17 – On SW 5th 17 – On SW 5th |

18 – At the end of SW 5th, looking west toward May Avenue |

|

2010 County Assessor’s Aerial Map. Is the above all there is, all that remains? Yeah, pretty much, and the Google map used above doesn’t include all of the Sandtown area. For a full view of what once was Sandtown, I’ve patched together aerial views from the Oklahoma County Assessor’s website, the aerial pieces being taken between March 19 and 29, 2010, and have emphasized the street names shown in the assessor’s map. Using the above Manly map as a guide, the original Sandtown area has been highlighted, the curvy part on the east being the former location of the North Canadian River. Click on the image below for a 1024 px wide view. Or, click here for a 2000 px wide image, or click here for a 2,599 px wide image, it showing the actual size of the assembled pieces from the assessor’s website. For the original map, 2,599 px wide, without my annotations or highlighting, click here. The assessor’s detailed lot and block information will only be readable in the 2,599 px wide views.

More noticeable in the larger views is that the outlines of by-gone streets and street names are observable, e.g., Katherine (same as SW 6th Street), the southern boundary of Sandtown which is shown as mostly being in the bed of the North Canadian River. I guess that the County Assessor’s office didn’t get the memo that the portion of the river shown is now the Oklahoma River.

Notice that much of the original Sandtown is empty space or, in some parts of the north and northeast areas, commercial property.

What happened — why do contemporary aerial maps, like the above, depict Sandtown areas that were previously occupied by homes, even if decrepit, being replaced by (1) grassland or by (2) commercial property, particularly in the north and northeast areas of Sandtown?

I’m not completely clear about this. Based upon articles in the Oklahoman in late 1962, my first impulse was to opine that the answer probably comes from activity by Oklahoma City’s Urban Renewal Authority (OCURA) in the 1960s-1970s. Three 1962 Oklahoman articles cause me to think this way. First, a pair of articles in the October 31, 1962, Oklahoman, reported as follows:

(Article 1) Official designation by the city council of Oklahoma City’s first blighted areas was urge Tuesday by the city planning commission. ¶ The planning board adopted and sent to city councilmen a report prepared by Sam B. Zisman, planning consultant, in which recommendations were made for designations of four geographic areas of the city for priority attention of the Urban Renewal Authority. ¶ They include: * * * Reno-May Renewal Area located south of Reno Ave. and east of May in the George Washington Carver School and Doffings Addition area.

(Article 2) Reno-May Area. Planners described this area as “wholly blighted” except for the George Washington school and a few non-residential establishments. ¶ The area has already been disrupted by clearance of right of way for the Downtown Expressway.

The third 1962 Okahoman article, on December 7, says that, among other things, the planning commission’s “Reno-May” area report had been approved by city council and said,

Three general areas of blight and a group of seven pocket areas were designated with the last month by the Oklahoma City Council and the city planning commission as suitable for a more detailed study and possible Urban Renewal projects. ¶ The three large areas included are the University Medical Center area, lying between NE 13 and the Rock Island Railroad, N. Lottie Ave. and the route of the future Lincoln Blvd. Expressway; south central area lying between Main St. and the floodway, Western Ave. and the Santa Fe railroad; and Reno-May, an area south of Reno Ave. and east of S May in the George Washington Carver School and Duffings [sic] Addition area.

I have thus far not located later Oklahoman reports or other sources which state, in fact, that the barren parts of Sandtown and/or the commercial developments seen in present day aerial maps were/are the result of OCURA activity such as occurred in the Deep Deuce or Medical Center areas where, after acquisition by OCURA, large areas were transformed into areas of oblivion and grass.

To test my hypothesis, I took a fairly close look at the Oklahoma County Clerk’s records after 1962 to see what I could find, particularly those on the east side of Sandtown — the original Doffings’s Suburban Addition in the northeast part which was never broken into lots or blocks, Morrisdale and Morrisdale 2nd Additions, just below that, and Lewis Addition, which formed the southeastern part of Sandtown.

I could locate no instance of property in those areas being acquired by OCURA. Possibly I missed something, and possibly the on-line version of the County Clerk’s records are incomplete, but if a conveyance to OCURA was present after 1962, I did not find it.

But I did find a few other things. A number of Oklahoma City notices were filed for record with the Oklahoma County Clerk concerning dilapidated structures in the area and a few tax deeds were issued for failure to pay county taxes. It reads as though Sandtown structures were destroyed, not by OCURA, but by Oklahoma City through its normal processes.

OKLAHOMAN ARCHIVES. I’ve rather thoroughly reviewed the Oklahoman archives from 1901 to the present time to locate anything I could find which mentioned “Sandtown” or “Sand Town” (since the Oklahoman used both names for the area), as well as some other search words and phrases, and that process resulted in hundreds of finds. Many were pretty useless as far as shedding light on Sandtown’s history is concerned. A summary of what I found is the following — and all that follows assumes that the Oklahoman reports were accurate, even though that was not always the case.

When Did Sandtown Become A Part Of Oklahoma City? The easy answer is March 11, 1930. The harder question is, When did Sandtown FINALLY become a part of Oklahoma City, and I am unable to give a definitive answer to that question based upon the Oklahoman’s reports.

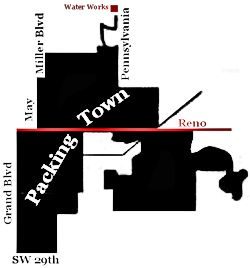

Prior to March 11, 1930, it was definitely outside Oklahoma City’s limits. A pair of articles appeared in the March 12, 1930, Oklahoman describing the annexation ordinance adopted by the city council on March 11. In one article, a map showing annexed areas is presented, part of which I’ve re-created here since the image quality in the on-line version is so poor. Click on the map for a larger view. The map shows an area called “Packing Town,” obviously broadly defined since parts of that area extend north of West Reno and begin south of the water works area on Pennsylvania. The map shows that the Sandtown area was included in the annexation.

Prior to March 11, 1930, it was definitely outside Oklahoma City’s limits. A pair of articles appeared in the March 12, 1930, Oklahoman describing the annexation ordinance adopted by the city council on March 11. In one article, a map showing annexed areas is presented, part of which I’ve re-created here since the image quality in the on-line version is so poor. Click on the map for a larger view. The map shows an area called “Packing Town,” obviously broadly defined since parts of that area extend north of West Reno and begin south of the water works area on Pennsylvania. The map shows that the Sandtown area was included in the annexation.

A March 13, 1930, article by Meredith Williams appeared in the Oklahoman which gave her condescending and somewhat poetic description of the Sandtown area that had been incorporated into the city limits. The headline read, “Sandtown, dreary waif in civic realms, not excited by new status.” Part of that article reads as follows, and it contains some interesting remarks (emphasis added) — and yes, I did have to look up a couple of words that were new to my vocabulary: choleric = extremely irritable or easily angered, irascible; acarpous = not producing fruit, sterile, barren. Read on …

That choleric and acarpous region which for years has been dubbed simply “Sandtown” officially was a part of Oklahoma City Wednesday and police prepared to cock an extra eye on the territory, while the city hall gleefully counted additional population by extending the city limits. ¶ Without ever becoming downright vicious, Sandtown for years had been a place of considerable mystery, and the residents there have fought out their battles among themselves, generally unmolested by such dignitaries as constables, deputy sheriffs and brass-buttoned cops. ¶ Sandtown stretches its dreary desolation between Reno avenue and the Canadian river, east of May avenue, like a patter of mush dumped on unoffending linen. It is low and flat. In summer it boils; in winter the wind whistles ominously through its decadent vegetation and the thin walls of its dwellings. ¶ Razors are sharp in Sandtown, and tempers quick. Mysterious fires have occurred there in the past, sometimes claiming lives as well as property. When there are neither knives, nor incendiary fires, nor prying eyes from outside to fear, there is always the river, which has more than once risen in anger and driven the residents from such homes as they possess. ¶ But now Sandtown is to have “protection.” It even became so important that when it was annexed by Oklahoma City a clause was put in the ordinance reciting that it being “immediately necessary for the protection of the public health, peace and safety,” Sandtown at once should be added to the capital, great center of oil, culture and Jamaica ginger. ¶ Protection, of course, includes not alone police. It also means sewers, water main, bath tubs, taxes, and the privilege of voting for councilmen and mayors. ¶ Anyone would suppose such high honors would turn Sandtown’s [illegible] head, that its very sand would turn to rich loam, or even to gold dust. ¶ Strangely enough, though, Sandtown turned the same morose, forbidding stare toward the city, its silence broken only by the muddy water of the river as it gurgled over a dead tree perpetually hymning, “cops acomin, cops acomin,” while the March wind hissed, “taxes, taxes, taxes.”

Interesting stuff it was that Ms. Williams wrote. However, one must wonder if her conclusions and remarks were based upon personal research — that is, did she actually deign to go into Sandtown to interview its residents — or was she merely parroting what was commonly understood by the white folk in the day. Make your own guess, but recall that her article was written in 1930.

Regardless, the March 11 annexation didn’t last long, certainly not for the Packingtown area and most probably not for Sandtown, as well.

… more coming shortly …